Credits: ESA, LFI & HFI Consortia. Background optical image: Axel Mellinger

By Hamish Johnston

In August the new Planck microwave observatory spent two weeks scanning the heavens — and today the European Space Agency has released the results of this first survey by the satellite instrument.

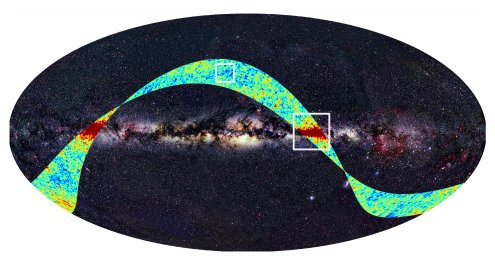

The image above shows the entire sky at optical wavelengths and the prominent horizontal band is the light shining from our own Milky Way. The superimposed strip shows the area of the sky mapped by Planck during the “first light” survey.

The colour scale shows the deviations of the temperature of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) from its average value (red is hotter and blue is colder). The discovery of these deviations won George Smoot the 2006 Nobel Prize and their study promises to tell us much about the early universe.

The large red strips trace radio emission from the Milky Way, whereas the small bright spots high above the Milky Way correspond to emission from the CMB itself.

Planck’s mission is to map out the CMB in the finest detail yet. The CMB was created 400,000 years after the Big Bang, when primordial protons, neutrons and electrons formed neutral atoms that allowed photons to finally move freely. The photons have continued to do so ever since, being stretched to microwave frequencies due to the expansion of the universe.

Planck will provide a glimpse of the very early universe. Cosmologists believe that the nascent universe underwent a period of extremely rapid growth called inflation — and Planck data should help physicists hone their models of how and why inflation occured.

The first all-sky map from Planck should be available in about six months.