Ian Randall reviews The History of Science in Bite-sized Chunks by Nicola Chalton and Meredith MacArdle

“Different branches of science explore literally everything in the universe, from its origins to its tiny particles, from the human body to rocks and minerals, and from the power of lightning to invisible forces such as X-rays, radioactivity and gravity.” Reading this excerpt from the introduction to Nicola Chalton and Meredith MacArdle’s recently republished book, The History of Science in Bite-sized Chunks, I find myself almost wishing I were able to juxtapose my thoughts on this work with a similar review by my younger self. As a pale, bespectacled, bookworm of a child, I had a voracious appetite for broadly pitched popular-science books. Back then I would have enjoyed poring uncritically through this dense yet accessible volume of facts – yet I am now left wondering whether this is a book I am able to unreservedly recommend.

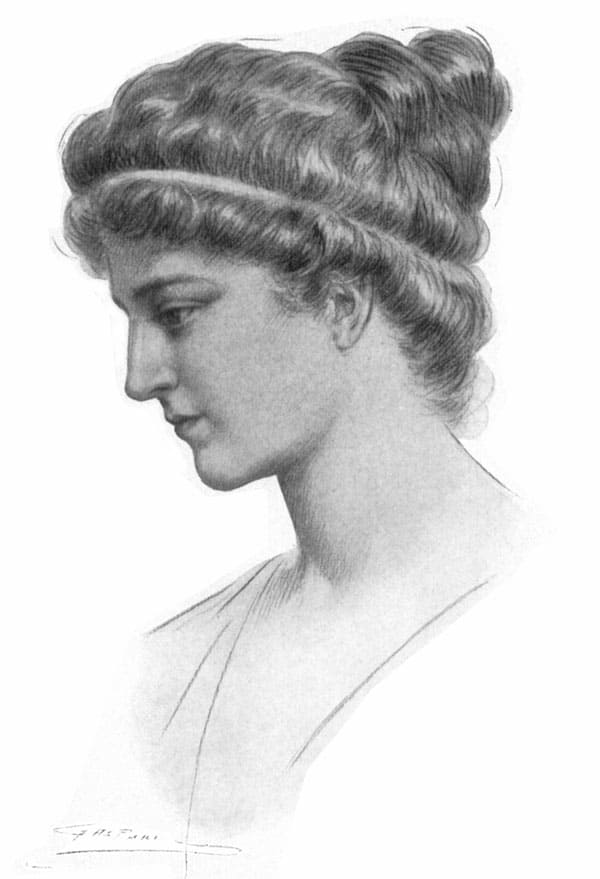

The volume must first be credited with the easy manner in which it synthesizes past and present snippets from across the diverse breadth of sciences. Although the back cover’s claim that the book touches upon “all the key discoveries and remarkable minds in each scientific field” may be inherently unrealistic, Chalton and MacArdle maintain a good flow throughout, with each covering a broad scientific area, from physics and chemistry to geology and metrology. I particularly enjoyed the section on third-century Egyptian scholar Hypatia, and that on Ahmed Zewail, inventor of the field of femtochemistry, both of whose work I was (one is ashamed to admit) previously unfamiliar with. There are also many enchanting anecdotes sprinkled throughout the pages – my favourite being René Descartes’ quip that Blaise Pascal, who had recently proved the existence of vacuums, “has too much vacuum in his head”.

While the narrative of science forges on in reality, the book comes to an oddly abrupt end, wrapping up with a summary of the current state of climate research, with little to guide the reader forward from this point. For the physicist, also, the section describing Schrödinger’s cat seems almost to muddle the thought experiment’s intended purpose with more recent interpretations of quantum mechanics. Meanwhile, it seems disingenuous and Western-centric to refer to US geographer William Morris Davis as the originator of geomorphology, only 14 pages after describing medieval Chinese polymath Shen Kuo as the first to hypothesize how land structures formed.

From physica to physics

The real issue with the volume, however, stems from how Chalton and MacArdle have handled that fact that the effort to relay the “big names” in science inherently draws into stark focus the regrettable and long-running gender bias in the whole enterprise. The book does not shy from noting the impact of other social factors on the history of scientific knowledge – for example, the persecution of Jewish researchers in Nazi-occupied territories. Yet it is conspicuous in its decision not to directly acknowledge the gender-bias issue or make more effort to highlight the contributions of women to science.

There are certainly prominent names absent from this volume – what of seismologist Inge Lehmann, discoverer of the Earth’s solid inner core; palaeontologist Mary Anning; primatologist and life-long conservationist Jane Goodall; or pioneering computer scientist Grace Hopper? It is especially sad to see a good proportion of the women who do appear in the book reduced to cursory mentions at the end of a section devoted to their male counterparts. Such pioneers as Ada Lovelace, Lise Meitner and Candace Pert could surely have filled a few paragraphs on their own merit. With this built-in flaw in mind, one wonders if, perhaps, it was in anticipation of such criticism that the book was rebranded from its previous and more problematic title: The Great Scientists (in Bite-sized Chunks)?

- 2019 Michael O’Mara Books 224pp £7.99pb