“Fusion is now within reach” and represents “one of the economic opportunities of the century”. Not the words of an optimistic fusion scientist but from Kerry McCarthy, parliamentary under-secretary of state at the UK’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

She was speaking on Tuesday at the inaugural Fusion Fest by Economist Impact. Held in London, the day-long event featured 400 attendees and more than 60 speakers from around the world.

McCarthy outlined several initiatives to keep the UK at the “forefront of fusion”. That includes investing £20m into Starmaker One, a £100m endeavour announced in early April to kickstart UK investment fusion fund.

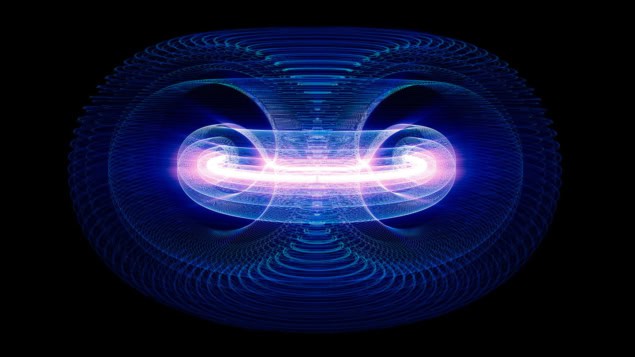

The usual cliché is that fusion is always being 20 years away, perhaps not helped by large international projects such as the ITER experimental fusion reactor that is currently being built in Cadarache, France, which has struggling with delays and cost hikes.

Yet many delegates at the meeting were optimistic that significant developments are within reach with private firms racing to demonstrate “breakeven” – generating more power out than needed to fuel the reaction. Some expect “a few” private firms to announce breakeven by 2030.

And these aren’t small ventures. Commonwealth Fusion Systems, based in Massachusetts, US, for example, has 1300 people. Yet large international companies are, for the moment, only dipping their toe into the fusion pool.

While some $8bn has already been spent by private firms on fusion, many expect the funding floodgates to open once breakeven has been achieved in a private lab.

Most stated that a figure of about $50-60bn, however, would be needed to make fusion a real endeavour in terms of delivering power to the grid, something that could happen in the 2040s. But it was reiterated throughout the day that fusion must provide energy at a price that consumers would be willing to pay.

On target

It is not only private firms that are making progress. Many will point out that ITER has laid much of the groundwork in terms of fostering a fusion “ecosystem” – a particular buzzword of the day – that was demonstrated, in part, by the significant attendence at the event.

And developments are not just being confined to magnetic fusion. Kim Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which is home to the National Ignition Facility, noted that the machine had recently achieved a fusion gain for the eighth time.

In a recent shot, she said that the device had produced 7 MJ with about 2 MJ having been delivered to the small capsule target. This represents a gain of about 3.4 – much more than its previous record of 2.4. Fusion industry outlines ambitious plans to deliver electricity to the grid by 2035

NIF, which is based on inertial confinement fusion rather than magnetic confinement, is currently undergoing refurbishment and upgrades. It is hoped that this will increase the energy input to about 2.6 MJ but gains of between 10-15 will be demonstrated if the technique can go anywhere.

Despite the number of fusion firms ballooning from a handful in the early 2010s to some 30 today, the general feeling at the meeting was that only a few will likely go on to build power plants, with the remainder using fusion for other sectors.

The issue is that no-one knew what technology would likely succeed, so all to play for.