The head of the €2bn Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is confident that the project will go ahead, despite Germany saying that it will pull out of the project in 12 months’ time. In a press conference held in Sicily today, where more than 250 radio astronomers gathered to discuss the project, SKA director-general Philip Diamond reiterated that the withdrawal would not have a “long-term effect” on what will be the world’s largest radio telescope when built in 2023 in Australia and southern Africa.

Progress was also made at the meeting on drawing together the 130 chapters that will make up the updated SKA “science book”, which will be released by the end of this year. Appearing 10 years after the previous version was published, the new SKA science book will set the direction of what will be the world’s most sensitive radio telescope. Germany was the third largest contributor to the publication, behind Italy and the UK.

Germany’s decision to withdraw was announced last week following a letter sent last month by Georg Schütte, the state secretary of the Germany’s federal science ministry (BMBF), to SKA director-general Philip Diamond. The letter informed SKA officials that Germany’s membership would end on 30 June 2015 – only two years after it first joined the organization. The BMBF took the decision because it is apparently under financial pressure as it has to find money for two large German-based projects – the X-ray Free Electron Laser in Hamburg and the Facility for Anti-Proton Research in Darmstadt.

This has come completely out of the blue. It will have a catastrophic impact on German astronomy

Michael Kramer, director of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn

“We’re obviously disappointed by Germany’s decision,” Diamond told Physics World. Although he says that the withdrawal will not have a major impact on the project “in the near future”, Germany’s decision has caused some concern among researchers. Germany had been expected to contribute towards the SKA’s construction and had already spent around €1m on a membership fee and contributed around €2.8m towards the €140m cost of the SKA’s design. Moreover, the move to pull out was apparently taken without consultation with the astronomy community. “This has come completely out of the blue,” says Michael Kramer, director of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn. “It will have a catastrophic impact on German astronomy.”

Germany has already played a major role in determining what science the SKA will do, with the German radio-astronomy community having been involved in a number of science working groups to define this. “German industry is involved in some of the design work too,” adds Diamond.

Extreme sensitivity

Germany is currently the 10th full member of the SKA Organisation, which includes researchers from Australia, Canada, China, Italy and South Africa working together to build a giant facility in the form of more than 3000 antennae with a total collecting area of one million square metres spread across Australia and southern Africa. The main site in South Africa is in the Karoo semi-desert region more than 500 km north-east of Cape Town, while most of the Australia antennae will be in the Murchison region, more than 300 km from the nearest town, Geraldton, on the country’s west coast.

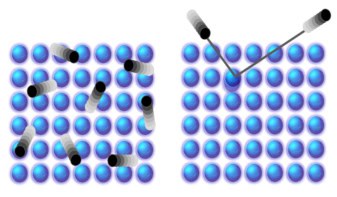

Construction of the first phase of the project is scheduled to begin in 2018. It will see an array of 254 dishes built in South Africa covering the bulk of the high- and mid-frequencies of the radio spectrum, while Australia will host the low-frequency section of the array with 96 dishes accompanied by approximately 250,000 individual dipole antennas. Astronomers will use the telescope to probe the early universe by looking as far back into time as the first 100 million years after the Big Bang. It will also search for life and planets, as well as study the nature of dark energy.

Design work for the first phase of the SKA got under way in 2013 and one of the key aims for 2014–2016 is to secure funding for the construction of the array. If all goes to plan, the first science results will appear from 2020 onwards, with the first phase of the array scheduled to be fully complete in 2023. Construction is scheduled to begin on phase two of the telescope in 2023 and is due to be finished by 2030.

Knock-on effect

The SKA Organisation will now have to manage Germany’s withdrawal, including finding other partners to pay for what the country might have contributed towards construction. Construction costs have yet to be divided between member states, but estimates – as a starting point to negotiations – show Germany would have been set to pay about 10–12% of the total. “That makes this decision to pull out even more baffling, as we don’t yet know how much Germany would have needed to pay,” says Kramer, who adds that his institute will continue to contribute to the SKA.

However, Diamond is hopeful that if Germany does not backtrack, then other countries could step into its shoes. “There are a number of other countries actively interested in joining the SKA, and we expect to see more in the next few years as we ramp up our funding search, which we’ve only just started,” says Diamond. But he thinks the real losers in the withdrawal will be German industry, which will not now be able to compete for engineering contracts to build the SKA, as well as the German science community, which will now find it harder to get time on the telescope. “That’s unfortunate given Germany’s long tradition of radio astronomy,” adds Diamond. “But interest in SKA science is strong in Germany, and we believe the German scientific community will continue to work with us, and we will support them in that.”