It will not have escaped the attention of readers that the International Year of Physics has started. We can think of the year as an experiment: is it possible to make physics more popular as measured by the number of physics students at schools and universities? It would be good to make physics more popular with the general public as well, but in the current climate we need to concentrate on the number of physics students.

Good physics teachers in schools, it goes without saying, are essential if physics is to remain in a healthy state. People become interested in physics for all sorts of reasons (parents, science fiction, something they read or see on television), but who has ever studied for a physics degree despite having a bad physics teacher? Sadly, many countries are in a vicious circle when it comes to physics teachers: fewer physics students leads to fewer physics teachers, leads to fewer students and so on. The different education systems in different countries mean that there is no single solution to these shortages, so the relevant national physical societies need to work with professional teaching organizations and governments to tackle the problem.

We should also recognize that there is something different about people who want to study physics at university: it is more than innate curiosity or mathematical ability, it is a streak of idealism or independence that takes them down a path that does not lead to a well-defined career. The physics community must ensure that such students are not somehow deterred from studying physics at university. It must also do more to tap into this mixture of curiosity and independence in girls and various minorities that are currently underrepresented in physics.

As already mentioned, good teachers are essential. So are lively and relevant curricula for schools: there is plenty going on in modern physics and astronomy to excite the young – the Huygens mission, iPods, DVDs and more – and it is possible to include the latest developments without sacrificing the basics (see “Back to the future” Physics World January 2004 p33). Better careers advice is also needed: many students and parents have little or no idea about the range of careers in education, research, business, industry, the City and elsewhere that are open to physics graduates.

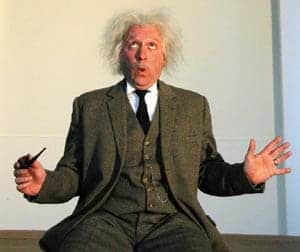

Professional physicists must also tailor their material when speaking to young people: while it was good to see so many students at the launch of the International Year of Physics in Paris last month, too many of the talks were too difficult for the predominantly young audience. Finally, all these efforts must continue after 2005. It will be several years before we know if the year of physics has been a successful experiment. There has certainly been a lot of media coverage of physics and Einstein in the past month, but the acid test will be the numbers of young people studying physics at schools and universities in years to come.