“Smart” textiles are a hot topic in materials science right now, with researchers in various organizations striving to combine light-emitting displays with flexible substrates. One approach is to sew diodes, wires, and optical fibres into textiles, but the resulting garments lack the soft, stretchy quality of their non-luminous counterparts. (They’re hard to wash, too.) The main alternative is to build thin-film light-emitting devices directly into the fabric, but the porous nature of textiles makes such structures hard to manufacture.

Now, however, scientists in Canada have found a truly fabulous solution: gold-coated tights, or pantyhose as they’re known in North America. Yunyun Wu, a PhD student in Tricia Carmichael’s materials-chemistry group at the University of Windsor, was out shopping for fabrics for her research when she realized that sheer fabrics would make a great platform for the transparent conductor in light-emitting devices. From there, Carmichael says, a “second lightbulb moment” led the group to choose pantyhose as “an ideal material” upon which to build their electrodes.

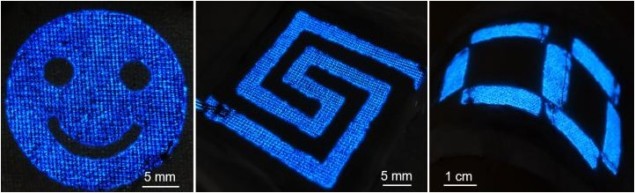

The researchers employed a metal-deposition technique called electroless nickel-immersion gold metallization to coat their pantyhose with gold film. Afterwards, they used the still-stretchy material to create light-emitting textiles emblazoned with a smiley-face emoji and a digital-clock-like display. The next step, they say, is to develop correspondingly flexible energy-storage components that can keep their 10-denier light-emitters going strong until the wearer decides to switch them off.

Love/hate relationship

“My observation is that about half the scientific community loves the h-index and half hates it, and the h-index of the scientist itself is a great predictor of whether s/he belongs to the first or the second group.” That is the wry conclusion of the physicist Jorge Hirsch, who invented the h-index in the early 2000s and appears to have fallen into the latter camp

The index attempts to quantify the academic output of a scientist in terms of number of papers published and the number of times those papers are cited by others. As Hirsch explains in the essay “Superconductivity, what the H? The emperor has no clothes”, “If your h-index is 25, you have written 25 papers that each have 25 or more citations, the rest of your papers have fewer than 25 citations each”.

While Hirsch believes that his index provides an “objective measure of scientific achievement,” he concedes that there have been some unintended negative consequences of its widespread use. One problem, according to Hirsch, is that it incentivizes a journal referee to approve a paper that cites the work of the referee – because doing so would boost the referee’s own h-index.

This bias, says Hirsch, could help explain why his theory regarding the role of holes in superconductivity never got going after he first proposed it in 1989. Hirsch has since written about 100 papers that “poke holes” in the widely-accepted BCS theory of superconductivity – but getting these accepted by journals has been a real struggle, he says.

These papers do not tend to cite the work of leading superconductor researchers, who are also referees, because these people are usually BCS stalwarts. Hirsch believes this could be part of his problem – although he does admit that an alternative explanation is that his ideas about holes could be wrong.