Bonnie Tsim says “hackathons” are a great way for scientists to apply their skills to the commercial world

Academics are often derided for their lack of entrepreneurial skills. Partly that’s because the curricula and training for undergraduate and postgraduate degrees are generally designed for those continuing in academia. Most students, however, prefer to explore other, non-academic career paths, in which the learning curve can be steep. Even students who do PhDs with an industry focus, for example at the UK’s centres for doctoral training, will face unusual challenges.

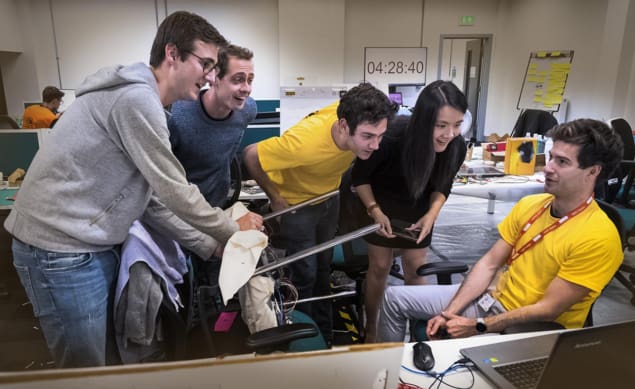

With such limited exposure outside the academic bubble, what else can be done for students who are interested in what industry may have to offer? What opportunities are there for students to meet and talk with people from industry and other backgrounds? One exciting way to address such issues, I’ve discovered, is for institutions to run “hackathons”. These were traditionally software-based challenges in which small teams of computer programmers and software developers created software. Those kinds of hackathons are still going strong, but they are now beginning to be used elsewhere with broader remits.

These hackathons usually run non-stop over a couple of days and can bring together people from a variety of backgrounds including science, arts, business and design to form interdisciplinary teams. In exposing researchers to an entrepreneurial, commercial and business environment in a very short space of time, they allow scientists to apply the skills they have developed during their degree in a different environment. Hackathons also highlight the importance of teamwork, resilience and communication skills.

Late last year, a group of PhD students from the University of Manchester hosted the first Graphene Hackathon at the Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre. It was a 24-hour event where 10 interdisciplinary teams, each of between four and six people, designed, prototyped and pitched a commercial product using conductive graphene inks in front of a panel for the chance to win investment and cash prizes. The event required not only prototyping a technology that was worthy of investment but also developing business cases to outline the value of the products.

In developing the graphene-ink products, the teams faced some unexpected challenges including malfunctioning Raspberry Pis, screen-printing problems and flimsy final prototypes. During the event, industry experts such as strategy consultants, business development managers and patent attorneys were on hand to advise the teams as they worked throughout the night.

The hackathon was a fantastic way for participants to apply what they had learnt and put it into practice. I was involved with a team that created “BackUP” – an array of thin graphene strain sensors that can be printed onto a fabric seat cover for lorry, bus and truck drivers. It worked by monitoring the pressure on different parts of the seat in real time to indicate bad posture. If a driver was leaning on one side, for example, then it would send real-time feedback to remind them to improve their posture. The product, which came second in the competition, was designed to increase the comfort and wellbeing of drivers and reduce the number of days they are forced to take off work due to debilitating back pain.

Innovation and skills

Events like the Graphene Hackathon foster innovation by challenging participants in a competitive environment, boosting the likelihood of conceptualizing potentially disrupting technologies. For me, the experience highlighted the importance of a “fail-fast” approach that differs from the slower pace of academic research in which projects often run for months and even years. Fail-fast is often used as a mantra within start-ups as it highlights the importance of determining the long-term viability of a product or strategy. If something is predicted to fail, it’s important to turn to a new idea without wasting more precious time and resources.

Indeed, the experience allowed me to apply the skills I developed from my physics degree to a commercial setting and made me realize the importance of thinking about fundamental research with a broader horizon. PhD students are in a unique place to develop their research and find commercial avenues for its applications. Hackathons can help widen the perspectives of participants, especially scientists who are looking to start spin-out companies. The skills needed to build a successful business are not too dissimilar from the attributes needed to become a successful scientist as both stand on the foundations of perseverance, problem solving and presentation skills.

I believe hackathons could be run in many other areas of research such as energy harvesting from renewable resources, applications using recycled materials, and waste recovery. A hackathon that marries software and hardware is a particularly innovative way for early-career scientists who want to break out into industry-based roles to gain valuable first-hand experience in an emulated start-up environment. Here’s to more hacks in the future.