In a major advance for nuclear physics, scientists on the STAR Detector at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in the US have spotted subtle but striking fluctuations in the number of protons emerging from high-energy gold–gold collisions. The observation might be the most compelling sign yet of the long-sought “critical point” marking a boundary separating different phases of nuclear matter. This similar to how water can exist in liquid or vapour phases depending on temperature and pressure.

Team member Frank Geurts at Rice University in the US tells Physics World that these findings could confirm that the “generic physics properties of phase diagrams that we know for many chemical substances apply to our most fundamental understanding of nuclear matter, too.”

A phase diagram maps how a substance transforms between solid, liquid, and gas. For everyday materials like water, the diagram is familiar, but the behaviour of nuclear matter under extreme heat and pressure remains a mystery.

Atomic nuclei are made of protons and neutrons tightly bound together. These protons and neutrons are themselves made of quarks that are held together by gluons. When nuclei are smashed together at high energies, the protons and neutrons “melt” into a fluid of quarks and gluons called a quark–gluon plasma. This exotic high-temperature state is thought to have filled the universe just microseconds after the Big Bang.

Smashing gold ions

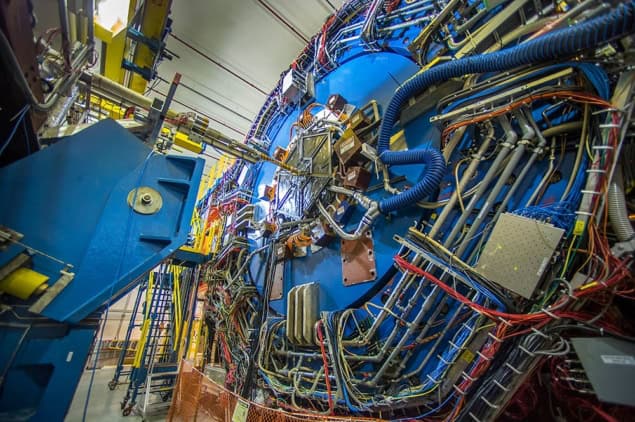

The quark–gluon plasma is studied by accelerating heavy ions like gold nuclei to nearly the speed of light and smashing them together. “The advantage of using heavy-ion collisions in colliders such as RHIC is that we can repeat the experiment many millions, if not billions, of times,” Geurts explains.

By adjusting the collision energy, researchers can control the temperature and density of the fleeting quark–gluon plasma they create. This allows physicists to explore the transition between ordinary nuclear matter and the quark–gluon plasma. Within this transition, theory predicts the existence of a critical point where gradual change becomes abrupt.

Now, the STAR Collaboration has focused on measuring the minute fluctuations in the number of protons produced in each collision. These “proton cumulants,” says Geurts, are statistical quantities that “help quantify the shape of a distribution – here, the distribution of the number of protons that we measure”.

In simple terms, the first two cumulants correspond to the average and width of that distribution, while higher-order cumulants describe its asymmetry and sharpness. Ratios of these cumulants are tied to fundamental properties known as susceptibilities, which become highly sensitive near a critical point.

Unexpected discovery

Over three years of experiments, the STAR team studied gold–gold collisions at a wide range of energies, using sophisticated detectors to track and identify the protons and antiprotons created in each event. By comparing how the number of these particles changed with energy, the researchers discovered something unexpected.

As the collision energy decreased, the fluctuations in proton numbers did not follow a smooth trend. “STAR observed what it calls non-monotonic behaviour,” Geurts explains. “While at higher energies the ratios appear to be suppressed, STAR observes an enhancement at lower energies.” Such irregular changes, he said, are consistent with what might happen if the collisions pass near the critical point — the boundary separating different phases of nuclear matter.

For Volodymyr Vovchenko, a physicist at the University of Houston who was not involved in the research, the new measurements represent “a major step forward”. He says that “the STAR Collaboration has delivered the most precise proton-fluctuation data to date across several collision energies”.

Still, interpretation remains delicate. The corrections required to extract pure physical signals from the raw data are complex, and theoretical calculations lag behind in providing precise predictions for what should happen near the critical point.

“The necessary experimental corrections are intricate,” Vovchenko said, and some theoretical models “do not yet implement these corrections in a fully consistent way.” That mismatch, he cautions, “can blur apples-to-apples comparisons.”

The path forward

The STAR team is now studying new data from lower-energy collisions, focusing on the range where the signal appears strongest. The results could reveal whether the observed pattern marks the presence of a nuclear matter critical point or stems from more conventional effects.

Meanwhile, theorists are racing to catch up. “The ball now moves largely to theory’s court,” Vovchenko says. He emphasizes the need for “quantitative predictions across energies and cumulants of various order that are appropriate for apples-to-apples comparisons with these data.”

Speed of sound in quark–gluon plasma is measured at CERN

Future experiments, including RHIC’s fixed-target program and new facilities such as the FAIR accelerator in Germany, will extend the search even further. By probing lower energies and producing vastly larger datasets, they aim to map the transition between ordinary nuclear matter and quark–gluon plasma with unprecedented precision.

Whether or not the critical point is finally revealed, the new data are a milestone in the exploration of the strong force and the early universe. As Geurts put it, these findings trace “landmark properties of the most fundamental phase diagram of nuclear matter,” bringing physicists one step closer to charting how everything – from protons to stars – first came to be.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.