Mad Science: Experiments You Can Do At Home – But Probably Shouldn't

Theo Gray

2009 Black Dog & Leventhal

£16.95/$24.95 hb 240pp

For experimentally minded readers, the warning “don’t try this at home” is a real killjoy. However, coming from Theo Gray, it is also a seriously good piece of advice. Mad Science: Experiments You Can Do At Home – But Probably Shouldn’t is a catalogue of inventive and terrifying things that Gray, a columnist with the Popular Science website and co-founder of the company behind Mathematica software, has done in the name of science. The book features step-by-step instructions, safety guidance and background information for 55 different experiments that range from a liquid-mercury motor to a dry-ice cloud chamber. As these two examples show, some of the experiments are far safer than others, and many have no place whatsoever in your garden shed – at least not if you want to see the shed again afterwards.

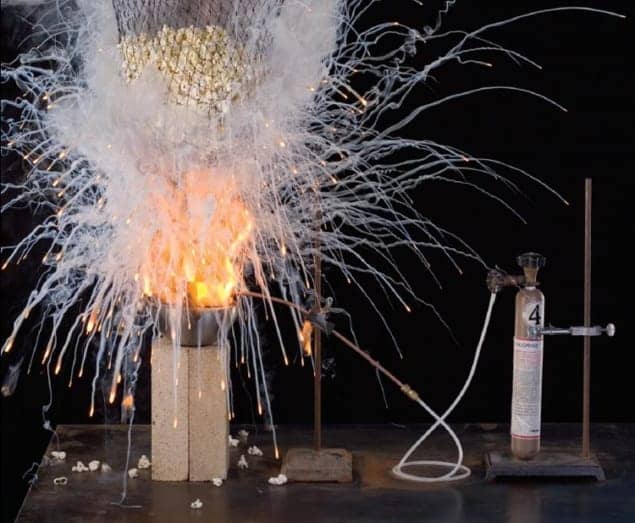

Figure 1, which shows what happened after Gray blew pure chlorine into liquid sodium, is a case in point. The result looks impressive. It will certainly salt your popcorn, but it could also kill you, Gray observes, adding that his safety preparations included “a clear path to run like hell” in the event of an uncontrolled chlorine leak. A separate experiment, which uses a bank of 12,000 V capacitors to crush a penny, gets a stark warning: brush against these capacitors while they are charged “and you are stone-cold dead, instantly”.

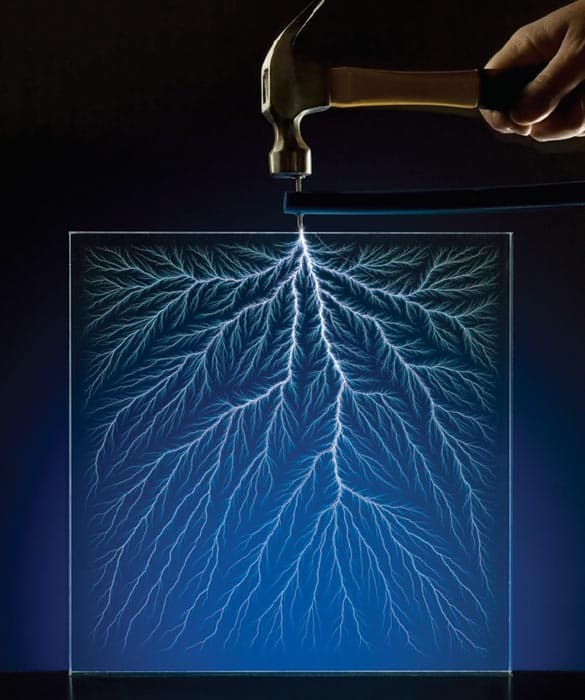

Other experiments are safer, but not necessarily easier to reproduce. Gray is a past master at sourcing rare materials: he won an Ig Nobel Prize in 2002 for building a table containing samples of nearly every element in the periodic table, including oddities like dysprosium and lutetium. Many university labs, let alone secondary schools or shed owners, will struggle to replicate the ingenuity on display in his book. For example, the “gravity cell” battery (figure 2) looks straightforward at first, as it requires nothing more dangerous than copper sulphate (which Gray helpfully notes is available at some garden centres). But it also needs zinc crow’s-foot electrodes, which are no longer available commercially; Gray had to make his own using molten zinc and a machined graphite mould. Similarly, the Lichtenberg figure (figure 3) was prepared using the Dynamitron particle accelerator at Ohio’s Kent State University – a Van de Graaff generator makes a poor (though far more accessible) substitute.

But although “experiments you can’t do at home” might have been a more accurate subtitle, Gray’s heart is clearly in the right place. This lavishly illustrated book allows us to see the results of his antics and appreciate the beautiful science behind them, without having to expose ourselves to the danger. What’s so mad about that?