Stefan Hutzler and Louise Bradley explain how they turned the famous pitch-drop experiment into an outreach activity

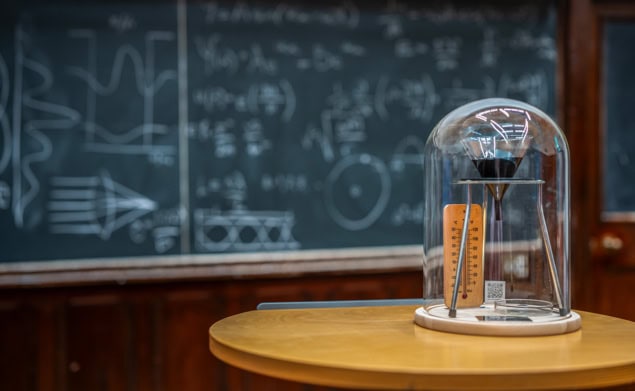

Nothing is really known about the origin of the world-famous “pitch-drop experiment” at the School of Physics, Trinity College Dublin. Discovered in the 1980s during a clear-out of dusty cupboards, this curious glass funnel contains a dark, black substance. All we do know is that it was prepared in October 1944 (assuming you trust the writing on it). We don’t know who filled the funnel, with what exactly, or why.

Placed on a shelf at Trinity, the funnel was largely ignored by generations of students passing by. But anyone who looked closely would have seen a drop forming slowly at the bottom of the funnel, preparing to join older drops that had fallen roughly once a decade. Then, in 2013 this ultimate example of “slow science” went viral when a webcam recorded a video of a tear-drop blob of pitch falling into the beaker below.

The video attracted more than two million hits on YouTube (a huge figure back then) and the story was covered on the main Irish evening TV news. We also had a visit from German news magazine Der Spiegel, while Discover named it as one of the top 100 science stories of 2013. As one of us (SH) described in a 2014 Physics World feature, the iconic experiment became “the drop heard round the world”.

Pitching the idea

Inspired by that interest, we decided to create custom-made replicas of the experiment to send to secondary schools across Ireland as an outreach initiative. It formed part of our celebrations of 300 years of physics at Trinity, which dates back to 1724 when the college established the Erasmus Smith’s Professorship in Natural and Experimental Philosophy.

An outreach activity that takes 10 years for anything to happen is obviously never going to work. Technical staff at Trinity’s School of Physics, who initiated the project, therefore experimented for months with different tar samples. Their goal was a material that appears solid but will lead to a falling drop every few months – not every decade.

After hitting upon a special mix of two types of bitumen in just the right proportion, the staff also built a robust experimental set-up consisting of a stand, a funnel and flask to hold any fallen drops. Each was placed on a wooden base and contained inside a glass bell jar. There were also a thermometer and a ruler for data-taking along with a set of instructions.

On 27 November 2024 we held a Zoom call with all participating schools, culminating in the official call to remove the funnel stopper

Over 100 schools – scattered all over Ireland – applied for one of the set-ups, with a total of 37 selected to take part. Most kits were personally hand-delivered to schools, which were also given a video explaining how to unpack and assemble the set-ups. On 27 November 2024 we held a Zoom call with all participating schools, culminating in the official call to remove the funnel stopper. The race was on.

Joining the race

Each school was asked to record the temperature and length of the thread of pitch slowly emerging from the funnel. They were also given a guide to making a time-lapse video of the drop and provided with information about additional experiments to explore the viscosity of other materials.

To process incoming data, we set up a website, maintained by yet another one of our technical staff. It contained interactive graphs showing the increased in drop length for every school, together with the temperature when the measurement was taken. All data were shared between schools.

After about four months, four schools had recorded a pitch drop and we decided to take stock at a half-day event at Trinity in March 2025. Attended by more than 80 pupils aged 12–18 and teachers from 17 schools, we were amazed by how much excitement our initiative had created. It spawned huge levels of engagement, with lots of colourful posters.

By the end of the school year, most had recorded a drop, showing our tar mix had worked well. Some schools had also done experiments testing other viscous materials, such as syrup, honey, ketchup and oil, examining the effect of temperature on flow rate. Others had studied the flow of granular materials, such as salt and seeds. One school had even captured on video the moment their drop fell, although sadly nobody was around to see it in person.

The drop heard round the world

Some schools displayed the kits in their school entrance, others in their trophy cabinet. One group of students appeared on their local radio station; another streamed the set-up live on YouTube. The pitch-drop experiment has been a great way for students to learn basic scientific skills, such as observation, data-taking, data analysis and communication.

As for teachers, the experiment is an innovative way for them to introduce concepts such as viscosity and surface tension. It lets them explore the notion of multiple variables, measurement uncertainty and long-time-scale experiments. Some are now planning future projects on statistical analysis using the publicly available dataset or by observing the pitch drop in a more controlled environment.

Wouldn’t it be great if other physics departments followed our lead?