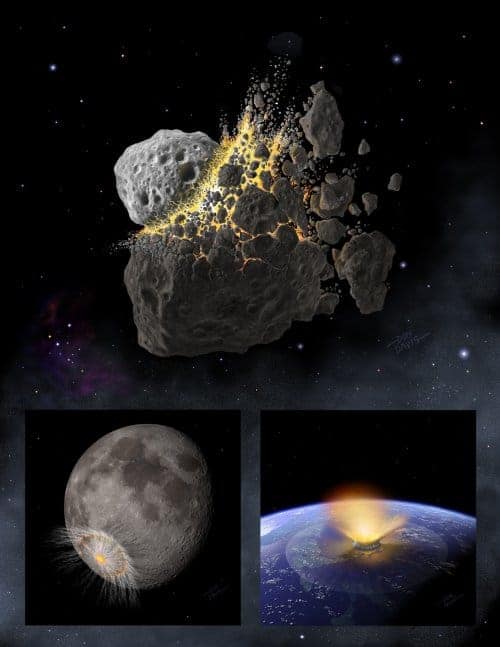

Strong evidence that the dinosaurs were killed-off 66 million years ago by an asteroid hitting Earth has been found in Chicxulub crater under the Gulf of Mexico. An international team has measured an abundance of the rare element iridium in the crater and similarly high concentrations of the element are known to occur in sediments laid down at the time of the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–Pg) extinction event, which saw many species on Earth vanish.

Measuring 200 km across, the Chicxulub crater is believed to have been created by an 11 km-wide asteroid crashing into Earth. The impact would have sent vast amounts of vaporized rock into the atmosphere, blocking out the Sun and creating a winter that could have lasted several decades. The result, scientists believe, was the mass extinction of 75% of species on Earth including the non-flying dinosaurs.

The crater was discovered in the 1990s, but the idea that the K–Pg extinction was caused by an asteroid impact was proposed a decade earlier by a team that included the physics Nobel laureate Luis Alvarez. They found an unusually high amount of iridium in sedimentary rocks laid down at the K–Pg boundary. Iridium is rare in the Earth’s crust because it is a siderophile, which means that it dissolves in iron and therefore tends to sink into the Earth’s core. Iridium is much more abundant in asteroids, leading Alvarez and colleagues to conclude that the vaporization of an asteroid released large amounts of iridium into the atmosphere, which then fell to the ground as dust as the dinosaurs disappeared.

Huge tsunamis

As well as the subsequent discovery of the Chicxulub crater, the impact extinction theory is backed up by evidence that huge tsunamis occurred in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean regions at the time. However, the evidence linking the Chicxulub impact to the K–Pg extinction is not conclusive. The iridium could have been put into the atmosphere by another asteroid impact or impacts; and some scientists have suggested that increased volcanic activity, rather than an asteroid, could have caused the extinction.

In 2016, Sean Gulick at the University of Texas at Austin and Joanna Morgan of Imperial College London led an international team of scientists on the International Ocean Discovery Program on an expedition to the Chicxulub crater. They took about 900 m of rock core samples and found a similar spike in iridium content in sediment laid down just after the crater was formed. Indeed, the sedimentary rock containing iridium is so thick that they were able to date the dust to about two decades after the impact.

Similar abundances

Studies of the cores also revealed high levels of several other elements associated with asteroids and have been found in similar abundances in K–Pg sediments at 52 sites around the world.

Dinosaur extinction linked to colliding asteroids

“We are now at the level of coincidence that geologically doesn’t happen without causation,” says Gulick. “It puts to bed any doubts that the iridium anomaly [in the geologic layer] is not related to the Chicxulub crater.”

A separate study of the cores done in 2019 reveals that the crater rock has been depleted of sulphur when compared to surrounding limestone. This suggests that the impact blew large amounts of sulphur into the air, where it would have contributed to the cooling and then fallen as acid rain – making the situation on the ground even worse.

The research is described in Science Advances.