By Edwin Cartlidge in Rome

Last week Italy’s energy agency ENEA put on a conference to celebrate the 50th birthday of its Casaccia research centre outside Rome. The occasion also marked the official restart of two veteran research reactors at the site, which, said the agency, represented the symbolic return of nuclear power to the country. A referendum held in the wake of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 led to all of Italy’s power reactors being shut down, but the current government announced two years ago that it was to return to the nuclear fold and start construction of a number of modern plants by the end of 2013.

There are still many people in Italy who oppose nuclear power, notwithstanding its newfound green credentials. And there are also plenty who believe that the government’s ambitious plans, ultimately to generate 25% of the country’s electricity from nuclear, are destined to become an expensive flop. Certainly, the meeting at Casaccia did not instill confidence.

Being a 50th birthday party, it was natural that scientists and engineers should take a look back at the early days of Italy’s nuclear programme, entertaining us with film clips that re-enacted some of the crucial events leading to Italian physicist Enrico Fermi’s operation of the world’s first nuclear reactor in 1942. But in all the various talks there seemed precious little to indicate that concrete steps are being taken to revive nuclear. Indeed, the politician in charge of Italy’s energy policy, Stefano Saglia, was supposed to come and tell us about the new nuclear programme, but he failed to show up.

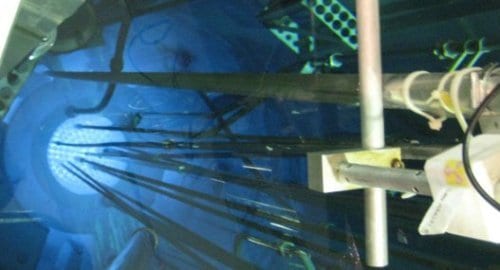

Although Casaccia focused predominantly on renewable energies and the environment throughout the 1990s it never entirely left behind its nuclear roots. In particular, it continued to operate two research reactors, the 1 megawatt thermal reactor TRIGA and the 5 kilowatt fast reactor TAPIRO. And it is the restart of these devices, following a two-year period of maintenance, that ENEA boss Giovanni Lelli declared on Wednesday marks the symbolic return to nuclear. But in fact it seems more of a case of business as usual.

TAPIRO will carry out tests that should help in the design of future generation-IV reactors and could also provide useful data in the construction and operation of the generation-III plants that Italy wants to start building in the next few years. But by and large the two reactors seem set to carry on doing what they have done for many years – developing nuclear medicine, providing isotopes to hospitals and industry, and analysing a range of materials. All laudable activities, but nothing to do with building new power stations. While being shown around a 50-year-old reactor, particularly one that gives off an eye-catching blue glow (see above), is fun, it does not provide convincing evidence that in a few years’ time Italians will once again enjoy the benefits of homegrown nuclear energy.