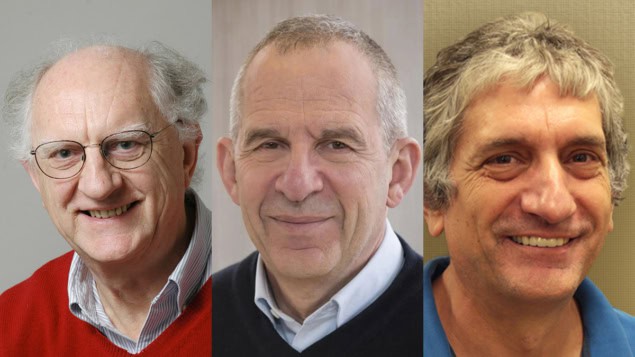

John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis share the 2025 Nobel Prize for Physics “for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantization in an electric circuit”.

The award includes a SEK 11m prize ($1.2m), which is shared equally by the winners. The prize will be presented at a ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December.

The prize was announced this morning by members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science. Olle Eriksson of Uppsala University and chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics commented, “There is no advanced technology today that does not rely on quantum mechanics.”

Göran Johansson of Chalmers University of Technology explained that the three laureates took quantum tunnelling from the microscopic world and onto superconducting chips, allowing physicists to study quantum physics and ultimately create quantum computers.

Speaking on the telephone, John Clarke said of his win, “To put it mildly, it was the surprise of my life,” adding “I am completely stunned. It had never occurred to me that this might be the basis of a Nobel prize.” On the significance of the trio’s research, Clarke said, “The basis of quantum computing relies to quite an extent on our discovery.”

As well as acknowledging the contributions of Devoret and Martinis, Clarke also said that their work was made possible by the work of Anthony Leggett and Brian Josephson – who laid the groundwork for their work on tunnelling in superconducting circuits. Leggett and Josephson are previous Nobel winners.

As well as having scientific significance, the trio’s work has led to the development of nascent commercial quantum computers that employ superconducting circuits. Physicist and tech entrepreneur Ilana Wisby, who co-founded Oxford Quantum Circuits, told Physics World, “It’s such a brilliant and well-deserved recognition for the community”.

A life in science

Clarke was born in 1942 in Cambridge, UK. He received his BA in physics from the University of Cambridge in 1964 before carrying out a PhD at Cambridge in 1968. He then moved to the University of California, Berkeley, to carry out a postdoc before joining the physics faculty in 1969 where he has remained since.

Devoret was born in Paris, France in 1953. He graduated from Ecole Nationale Superieure des Telecommunications in Paris in 1975 before earning a PhD from the University of Paris, Orsay, in 1982. He then moved to the University of California, Berkeley, to work in Clarke’s group collaborating with Martinis who was a graduate student at the time. In 1984 Devoret returned to France to start his own research group at the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique in Saclay (CEA-Saclay) before heading to the US to Yale University in 2002. In 2024 he moved to the University of California, Santa Barbara, and also became chief scientist at Google Quantum AI.

Martinis was born in the US in 1958. He received a BS in physics in 1980 and a PhD in physics both from the University of California, Berkeley. He then carried out postdocs at CEA-Saclay, France, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado, before moving to the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2004. In 2014 Martinis and his team joined Google with the aim of building the first useful quantum computer before he moved to Australia in 2020 to join the start-up Silicon Quantum Computing. In 2022 he co-founded the company Qolab, of which he is currently the chief technology officer.

The trio did its prizewinning work in the mid-1980s at the University of California, Berkeley. At the time Devoret was a postdoctoral fellow and Martinis was a graduate student – both working for Clarke. They were looking for evidence of macroscopic quantum tunnelling (MQT) in a device called a Josephson junction. This comprises two pieces of superconductor that are separated by an insulating barrier. In 1962 the British physicist Brian Josephson predicted how the Cooper pairs of electrons that carry current in a superconductor can tunnel across the barrier unscathed. This Josephson effect was confirmed experimentally in 1963.

Single wavefunction

The lowest-energy (ground) state of a superconductor is a macroscopic quantum state in which all Cooper pairs are described by a single quantum-mechanical wavefunction. In the late 1970s, the British–American physicist Anthony Leggett proposed that the tunnelling of this entire macroscopic state could be observed in a Josephson junction.

The idea is to put the system into a metastable state in which electrical current flows without resistance across the junction – resulting in zero voltage across the junction. If the system is indeed a macroscopic quantum state, then it should be able to occasionally tunnel out of this metastable state, resulting in a voltage across the junction.

This tunnelling can be observed by increasing the current through the junction and measuring the current at which a voltage occurs – obtaining an average value over many such measurements. As the temperature of the device is reduced, this average current increases – something that is expected regardless of whether the system is in a macroscopic quantum state.

However, at very low temperatures the average current becomes independent of temperature, which is the signature of macroscopic quantum tunnelling that Martinis, Devoret and Clarke were seeking. Their challenge was to reduce the noise in their experimental apparatus, because noise has a similar effect as tunnelling on their measurements.

Multilevel system

As well as observing the signature of tunnelling, they were also able to show that the macroscopic quantum state exists in several different energy states. Such a multilevel system is essentially a macroscopic version of an atom or nucleus, with its own spectroscopic structure.

The noise-control techniques developed by the trio to observe MQT and the fact that a Josephson junction can function as a macroscopic multilevel quantum system have led to the development of superconducting quantum bits (qubits) that form the basis of some nascent quantum computers.