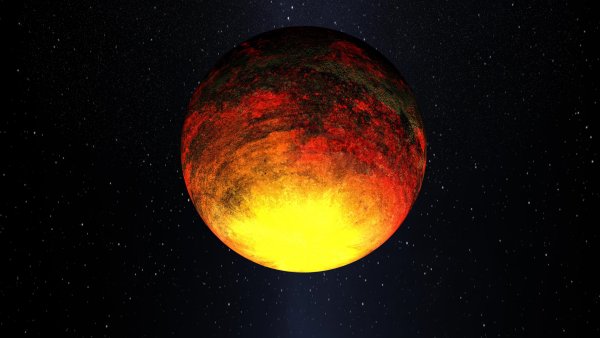

The first rocky exoplanet has been discovered by NASA’s Kepler space telescope, according to the mission’s deputy science team leader Natalie Batalha. The planet is called Kepler-10b and has a density on par with that of iron – making it much denser than Earth. The exoplanet orbits a star about 560 light years from Earth.

Kepler-10b is about 20 times closer to its host star than Mercury is to the Sun – and as a result its surface temperature is expected to be as high as 1400 °C. It always shows the same side to its star and is likely to have oceans of molten rock on its day side and a solid night side, according to Batalha. It has an orbital period of about 0.84 days and its star is known to be about the same size as the Sun.

Since the discovery of the first extrasolar planet (exoplanet) in 1995, over 500 more have subsequently been unveiled. While most of these are gas giants like Jupiter, astronomers are getting better at finding smaller exoplanets that could be more similar to Earth. Before Kepler-10b was identified, the best candidate was Corot-7b. While Corot-7b could indeed be rocky, its star is very active, making it difficult to accurately determine its density.

Three key measurements

Kepler-10b, however, is a very different case because its star is very old – about 8 billion years – which means that it is very quiet and much easier to deal with. The team determined the planet’s density by making three different observations. First, they determined its radius relative to the star’s by measuring how much light it blocks when it transits between Earth and its star. Then they determined its mass (again relative to its star) by measuring the wobble of the star caused by the orbiting planet. The final, and crucial step was to determine the radius and mass of the star itself, which was done by measuring the vibrational frequency of “starquakes” on the star.

Putting it all together the team believes that the planet’s density is about 8.8 g/cm3, which is denser than iron.

“This is the first unquestionably rocky planet,” said Batalha today the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle. “Its discovery is an important milestone for humanity,” she added. Geoff Marcy of the University of California at Berkeley, who was not involved in the work, said that the discovery “will go into every textbook on astronomy”.

Night and day temperatures

Batalha said that the Kepler team is now studying a possible modulation in the amount of light that reaches the telescope during the planet’s transit. This could allow the researchers to determine the temperatures of the day and night surfaces of the planet. While Kepler-10b is similar to Earth in some ways, it is not within the habitable zone around its star, where life could emerge – the Kepler group already knows it is much to hot for life as we know it.

One mystery surrounding Kepler-10b is how it managed to get so close to its star. Edward Guinan of Villanova University believes that it could be the remains of a gas giant like Jupiter that got so close to its star that the gas was blown off and only the rocky core remained.