The start-up of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN could be delayed after three of the magnets used to focus and manipulate the accelerator's proton beams failed preliminary tests at CERN earlier this week. The magnets were built at Fermilab in the US, which announced the failure on its Web site. Although CERN has not yet issued a formal statement on the set-back, it looks increasingly unlikely that the LHC will come on-line this year as planned.

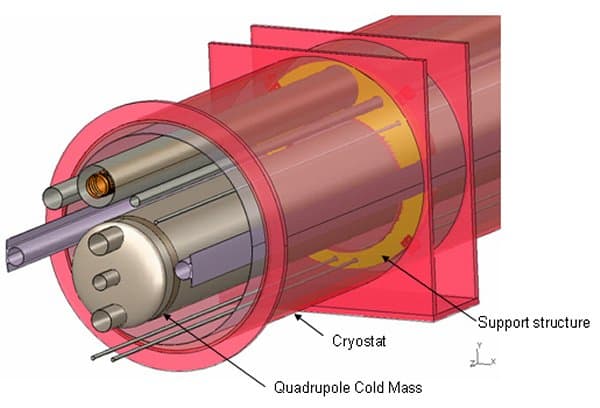

The €6.3bn LHC — the biggest experiment ever in particle physics — will accelerate protons in opposite directions around a 27-km-long ring and smash them together at energies close to 14 TeV. The protons will be guided around the ring by some 6000 superconducting magnets of various types. These include 392 “quadrupole” superconducting magnets that are designed to focus the proton beams before they collide at four interaction points around the accelerator.

Earlier this week, however, scientists at CERN performing preliminary tests on three of these quadrupoles witnessed a serious failure when structures supporting one of the magnets broke at a pressure of 20 atmospheres in response to “asymmetric forces” that were applied during the test. It is essential that the magnets can survive such unwanted pressures, which will occasionally be generated when the LHC is up and running.

These high pressures will occur if the superconducting magnets, which store huge amounts of energy, warm up inadvertently — for example, if faults in the magnet arise or if part of the proton beam careers off course and hits the magnet. This warming process, which is known as “quenching”, causes the magnets to lose their ability to superconduct and release their stored energy. Although the LHC contains a special protection system that will kick in to distribute the unwanted heat evenly through the rest of the magnet and so prevent the coil from melting, the magnets will still be subjected to enormous pressures.

Fermilab nor CERN do not yet know why the magnets failed. According to Fermilab, however, four engineering reviews of the magnets were carried out between 1998 and 2002, none of which appear to have addressed the asymmetric loads. The only tests on the magnets while they were still at Fermilab were performed on single magnets, which would never develop such loads. Fermilab is now planning an “external review of the factors that led to the magnet failures” and says it is working with staff at CERN to address the problem.

Originally slated for 2005 start-up, the LHC has already suffered several delays. CERN was caught out in 2001 when it emerged that the LHC was to cost 30% more than originally envisaged and was also running behind schedule. The committee that reviewed CERN’s operations in the light of these overruns recommended that the collider’s start date be put back from 2005 to 2007, and the lab will have been anxious to ensure that this date does not slip any further.