Researchers have created a new terahertz radiation emitter with highly-sought-after frequency adjustment capability. The compact source could enable the development of futuristic communications, security, biomedical and astronomical imaging systems.

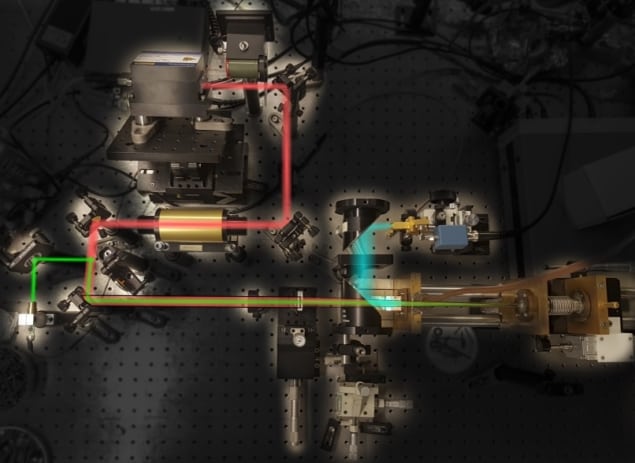

The high bandwidth, high resolution, long-range sensing and ability to visualize objects through materials, makes terahertz electromagnetic frequencies much-coveted. However, the costliness, bulk, inefficiencies and lack of tunability of traditional terahertz emitters has stymied these promising avenues. This new combined laser terahertz source, product of a collaboration between researchers at Harvard, the US Army, MIT and Duke University, paves the way for future technologies, from T-ray imaging in airports and space observatories, to ultrahigh-capacity wireless connections.

“Existing sources have limited tunability, not more than 15-20% of the main frequency, so it’s fair to say that terahertz is underutilized,” explains co-senior author Federico Capasso from Harvard University. “Our laser opens up this spectral region, and in my opinion, will have revolutionary impact.”

The team has now described the theoretical proof and demonstration of this widely tunable and compact terahertz laser system (Science 10.1126/science.aay8683).

Perfect partnership

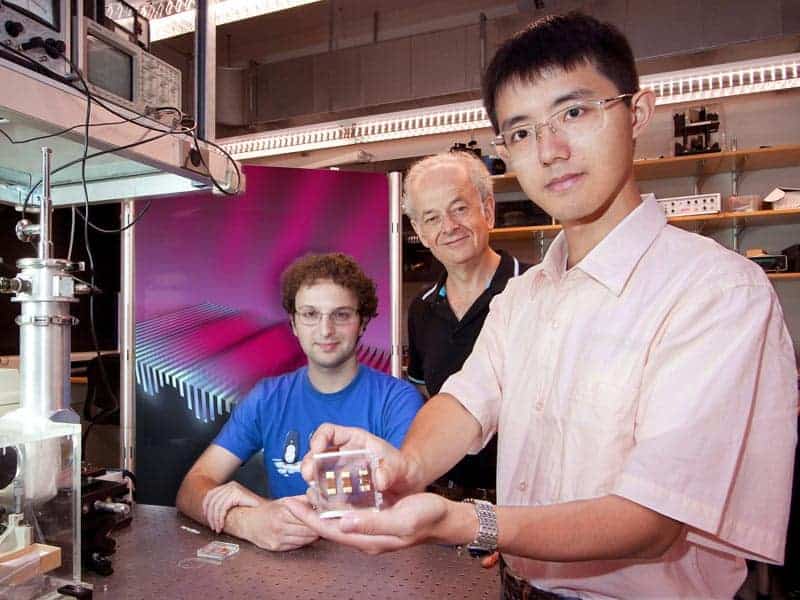

Capasso is no stranger to laser technology. He invented a compact tunable semiconductor laser, the quantum cascade laser (QCL), which is used commercially for chemical sensing and trace gas analysis. The QCL emits mid-infrared light, the spectral region where most gases have their characteristic absorption fingerprints, to detect low concentrations of molecules.

But it wasn’t until a conference in 2017 when Capasso met Henry Everitt, senior technologist with the US Army and adjunct professor at Duke University, that the idea to apply the widely tunable QCL to a laser with terahertz ability, formed.

Everitt, alongside Steven Johnson’s group at MIT, theoretically calculated that terahertz waves could be emitted with high efficiency from gas molecules held within cavities much smaller than those currently used on the optically pumped far-infrared (OPFIR) laser – one of the earliest sources of terahertz radiation. Like all traditional terahertz sources, the OPFIR was inefficient with limited tunability. But, guided by the theoretical calculations, Capasso’s team were able to use the QCL to dramatically increase the terahertz tuning range of a nitrous oxide (laughing gas) OPFIR laser.

“The same laser is now widely tunable – it’s a fantastic marriage between two existing lasers,” says Capasso.

Universal use

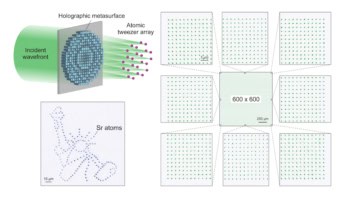

In initial experiments with the shoe-boxed sized QCL pumped molecular laser – QPML – the researchers demonstrated that the terahertz output could be tuned to produce 29 direct lasing transitions between 0.251 and 0.955 THz.

It was Johnson and Everitt’s theoretical models that highlighted nitrous oxide as a strongly polar gas with predicted terahertz release in the QPML. Similarly, a whole menu of other gas molecules have been predicted for terahertz generation at different frequencies and tuning ranges. Using this menu, it should be possible to select a gas laser appropriate for almost any application.

Terahertz scanning acquires sense of direction

“This is a universal concept, because it can be applied to other gases,” says Capasso. “We haven’t quite reached one terahertz, so next thing is to try a carbon monoxide laser and go up to a few terahertz, which is very exciting for applications!”

Both Capasso and Everitt are particularly keen to use their laser to look skywards and sensitively identify unknown spectral features in the terahertz region. The team is developing higher power terahertz QPMLs for astronomical observations, while also eagerly working towards other commercial applications.