Laura Bassi might not be a household name, but she was one of the shining stars of 18th-century Italian physics – and could well have been the first woman to have forged a professional scientific career, as Paula Findlen explains

Two hundred years before Marie Curie received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, one of her most interesting predecessors, the physicist Laura Bassi (1711–78), was born in the city of Bologna. A contemporary of the French mathematical physicist Émilie du Châtelet, Bassi enjoyed great fame as a teacher and experimentalist. Her long, productive career also coincided with the development of experimental physics as a discipline. Like Châtelet, Bassi was widely known throughout Europe, and as far away as America, as the woman who understood Newton. The institutional recognition that she received, however, made her the emblematic female scientist of her generation. A university graduate, salaried professor and academician (a member of a prestigious academy), Bassi may well have been the first woman to have embarked upon a full-fledged scientific career.

In 1803, for example, the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande wrote admiringly of Bassi, recalling his encounter with her almost 40 years earlier. Lamenting the lack of support for women interested in science in his own country, he argued that Bassi’s example “must be followed in France”. Lalande had travelled to Bologna, second city of the Papal States, visiting its porticos, paintings and churches, and indulging himself in the culinary pleasures of Bologna. But the highlight of his visit had been the opportunity for him to meet Italy’s most famous female professor.

Bassi had begun teaching in Europe’s oldest university in December 1732 and a pilgrimage to see her was an obligatory stop for any scientist making a Grand Tour of the continent. In 1764, for example, the physician John Morgan – Benjamin Franklin’s friend and founder of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia – watched as Bassi demonstrated Newton’s prism experiments in her family laboratory on Bologna’s Via Barberia. He was well aware that Bassi and her husband Giuseppe Veratti were experimentalists who strongly supported Franklin’s theory of electrical attraction and repulsion. Morgan promised to tell his famous American colleague that he had met them in Bologna.

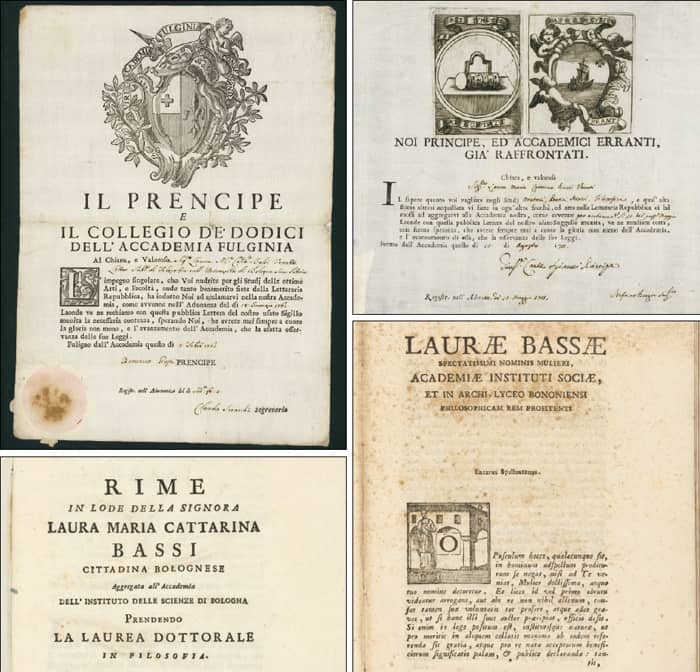

Fat and learned Bologna may have been, but it was also jokingly known as a “paradise for women” because of its habit of celebrating female success. In the Middle Ages Bologna reputedly produced women famous for their legal acumen; during the Renaissance it abounded in female artists. Indeed, Bassi is only the second woman, for whom we have documentary evidence, to have ever received a university degree, doing so on 17 April 1732 – five years after the death of Sir Isaac Newton. (The first was Elena Cornaro Piscopia, who received a degree in philosophy from the University of Padua in 1678.)

Almost from the start, Bassi was presented as a Newtonian physicist to signal her radical modernity. Poems were written celebrating Bassi’s explanation of Newton’s famous prism experiment, describing her account of refraction as the “sevenfold light” projecting “Great Britain’s shadow” across Italy. News of her accomplishments travelled far and wide. In Britain and France, readers of reports of Bassi’s newfound fame and institutional recognition wondered why Italy rejoiced in its learned women, when their own seemed relatively neglected. In Germany, reports of a female graduate inspired at least one father to consider whether his daughter might grow up to be the next Bassi. (Dorothea Erxleben in fact went on to become the first German woman to receive a university degree, from Halle in 1754.)

During her long and fascinating career, Bassi held numerous professorships and academy memberships, beginning with her appointment as professor of “universal philosophy” at the University of Bologna in December 1732. She subsequently taught experimental physics for the Collegio Montalto (1766–78) – a residential college for scholarship students from the Marches studying for the priesthood in Bologna – and was ultimately awarded the prestigious chair in experimental physics of the Bologna Institute in 1776, in acknowledgment of her outstanding reputation as one of the best physics teachers of her generation. A young Alessandro Volta – later to become inventor of the battery – eagerly sent Bassi his earliest publications, hoping to gain her approval of his work.

A lowly start

Bassi’s celebrity status in adult life belied her relatively modest beginnings. Her father was a lawyer, while her mother Rosa Maria Cesari was often ill. Bassi grew up among her father’s books, and during his frequent visits to the Bassi home to tend to her mother’s ailments, the family physician Gaetano Tacconi noticed that their studious only child seemed to have a lively mind and great facility with Latin. Tacconi encouraged her father Giuseppe to let him tutor her in philosophy – a subject that all doctors learned as part of their medical education. As a result, Bassi received the bulk of her tuition from him at home, including the study of Aristotelian, Galilean and Cartesian physics.

By the time Bassi was a teenager, Tacconi felt ready to let others know about his star pupil, rather like Henry Higgins unveiling Eliza Doolittle in the play Pygmalion. In fact, she went on to succeed beyond his wildest expectations – something that was to become a source of tension between the two of them as the pupil surpassed the master. By the start of 1732, virtually everyone in Bologna knew of her. People crowded into her house to listen to the 20-year-old debate just about every aspect of the history of philosophy and physics with the city’s leading professors and academicians. Indeed, Bologna’s archbishop Prospero Lambertini – who believed in acknowledging talent wherever it might be found – paid a personal visit to assure himself that Bassi was truly all that her admirers reported her to be. His support helped to launch Bassi’s scientific career and in March 1732 she became the first female member of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna Institute, which was equivalent to other recent scientific societies such as the Royal Society. It was the first step towards a spectacularly public life as a female scientist in the Age of Enlightenment.

The institutional recognition that Bassi received made her the emblematic female scientist of her generation

The Bologna Academy, which still exists today, was initially reluctant to make Bassi a precedent for admitting other women. They considered her appointment as an academician to be purely honorific and did not expect her to participate in the ordinary business of the academy. This was also true of Bassi’s university position. Her professorship was created specifically for her, beyond the normal number of faculty positions. Neither appointment was without controversy since there were many young male academics waiting for such opportunities. Funding then, as now, was always tight and some of her older male colleagues – and even at least one other learned woman – considered it indecent for a young woman to be “always in the middle of a meeting of men”, debating the secrets of nature with them. Nonetheless, archbishop Lambertini’s view that women of talent deserved recognition prevailed, although with an explicit injunction that Bassi only lecture occasionally when she was specifically asked by her employers to do so “by reason of sex”. This would, for example, be when a distinguished visitor arrived, or in one of Bologna’s famous public debates on anatomy during carnival time, or on one occasion when a degree was conferred. This restriction was felt to be an important concession to the question of modesty and decency.

Shock tactics

Had Bassi accepted the terms of her position as they were defined in 1732, there would be little more to say about her life and work. From the start, however, she felt that she had been offered an extraordinary opportunity to pursue her intellectual passions and contribute to the betterment of society with her knowledge. Far from being honoured, she was annoyed. Bassi politely but firmly requested that the restrictions on her teaching be lifted. When this request was ignored, she concentrated instead on a programme of additional study designed to increase her value as a scientist. She shocked a number of people by requesting a licence to read books that had been prohibited by the Roman Catholic Church. These included many works by Protestant scientists as well as the writings of Galileo and Descartes, all of which she deemed necessary to her ambitions. Recognizing the limits of her early education, which did not include advanced mathematics, Bassi studied calculus with Gabriele Manfredi. She also apprenticed herself with the city’s professor of experimental physics and chemistry, Jacopo Bartolomeo Beccari. Both were members of the Royal Society and had stellar reputations. This postgraduate education provided her with the skills to contribute substantively to an emerging teaching and research programme of Newtonian physics then under development.

In February 1738 Bassi made another momentous decision. She married the physician and fellow professor Giuseppe Veratti, who would affectionately call her Cara Laurinda. When a friend joked that she must have encountered her future spouse doing Newton’s prism experiments in the dark, following public criticisms by moralists who declared that she was now probing the secrets of nature with her body rather than her mind, Bassi tartly responded in a moving letter that she wrote to the physician Giovanni Bianchi in 1738: “I have chosen a person who walks the same path of learning, and who, from long experience, I was certain would not dissuade me from it.” She was then two months pregnant with the first of their eight children, five of whom survived infancy.

Together, Bassi and Veratti enthusiastically promoted a programme of Newtonian experimental physics in Bologna for almost half a century, supporting each other’s aspirations in a scientific partnership. Their marriage permitted Bassi to regularly invite guests to discuss physics with her without violating the restrictions placed upon her teaching; after all, young unmarried women were at the time expected to behave with utmost propriety and her being often alone with men before her marriage had caused plenty of gossip.

Gradually, their home on Via Barberia filled with instruments necessary for teaching and experimentation. Veratti explored the relationship between medicine, physiology and animal electricity, performing experiments that would inspire a number of younger colleagues including Luigi Galvani, who became famous for his work on reanimating the legs of dissected frogs with an electrical charge. Bassi initially worked on classical problems that made use of her training as a mathematical physicist and went on to publish papers on exceptions to Boyle’s law, mechanics and hydrometry.

Yet she consistently found herself gravitating towards questions that involved her skills as an experimentalist: problems of refraction, the nature of electricity and eventually the composition of air. Had these papers survived, we would know a great deal more about her contributions to each of these subjects. Yet it is nonetheless apparent that she was a great follower of the Newtonian programme of research throughout the 18th century, including the work of Stephen Hales, Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Priestley. She was a scientist determined to keep up with the times in which she lived.

Barred from the club

In 1745 Bassi’s patron Lambertini, by then Pope Benedict XIV (1740–58), decided to rejuvenate the Bologna Academy by creating an elite tier of academicians who would be known as the Benedictines. Those selected for this honour would be paid an annual stipend of 50 lire, with the obligation to present their research annually. When Bassi discovered she was not among the 24 Benedictines, she wrote to Rome to present her credentials for the pope’s consideration. Strategically invoking her exceptionality, Bassi requested that the pope make her the 25th member of this new group. Benedict XIV agreed. But once again, her male colleagues were confronted with the uncomfortable fact of Bassi’s ambition. She still failed to persuade them that she should be given the full privileges of membership, such as voting rights and attendance at meetings. In all other respects, however, Bassi’s colleagues acknowledged her desire to participate fully in the business of advancing scientific knowledge in her native city. They also began to admit more women as honorary members of the Bologna Academy, including Châtelet in 1746 and the Milanese mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi in 1748. In an era in which neither the Royal Society of London nor the Paris Academy of Sciences admitted any women, Bologna was indeed a city of scientific women.

Bassi’s passion for physics was, in part, a love affair shared by an entire society that grew up enthralled with the discoveries of the new science

In 1749 Bassi officially opened her “domestic school” at home. Her eight-month course of daily lessons “accompanied by experiments” brought renewed and more lasting fame. Bassi offered far more in-depth instruction than either the university, with its traditional curriculum of natural philosophy, or the Bologna Institute, with its weekly demonstrations of experimental physics. Young men came from all over Italy and as far away as Greece, Spain and Germany to study with her as her skill in combining the theoretical and experimental aspects of physics became well known. Among them was her young cousin Lazzaro Spallanzani, who was so inspired by Bassi’s teaching that he gave up his legal studies to become an experimenter. Spallanzani asked Bassi to participate in his work as a young physics professor, invited her to confirm some of his experiments and dedicated an early publication to his famous cousin whom he affectionately called his “venerable teacher”. Another young colleague encouraged her and Veratti to apply for professorships in Padua when vacancies opened up, hoping they would join him in leaving their native city for this rival institution. They do not seem to have pursued his suggestion, however.

“In our time experimental physics has become such a useful and necessary science,” declared Bassi in 1755, noting with pride that her private lessons had done more to animate this subject than anything either of the institutions that paid her salary – but would not let her teach publicly – had ever done. The Senate of Bologna acknowledged the justice of her observation that she did something that mattered for the greater good. Uncharacteristically, they gave her a pay rise, though on one condition: that she continue her school of experimental physics. At the age of 44, Bassi had finally accomplished her goal of being respected for what she did rather than who she was.

The culmination of this appreciation would be her appointment as the Bologna Institute professor of experimental physics in 1776, two years before her death. Although her elevation was not without the usual grumbling from some – that she always asked for more than was her due – such opposition by then seemed relatively muted. The Bologna academicians, in the end, had learned to live with the century’s most famous female scientist as their colleague for almost 45 years. Veratti took a job as her assistant and together they trained their youngest son Paolo as their successor.

Lasting legacy

Given Bassi’s many scientific endeavours, it is natural to wonder why her contributions are hardly known today. One reason is that only four of her papers appeared in print during or after her lifetime. The Bologna Academy archives do, however, contain a list of 32 research papers that she presented annually between 1746 and 1777, in fulfilment of her duties as a Benedictine. When others asked after Bassi’s death when her papers might appear, Veratti lamented her habit of publishing little, suggesting it was because she expected so much from her work that she had not wanted to rush her ideas into print.

Sadly, all but one of her unpublished papers disappeared during the disruptions of the Napoleonic era. Yet even without this material, we must conclude that Bassi contributed to the advancement of knowledge primarily through conversation, demonstration, experimentation and explanation. She produced the kinds of incremental results that tend to accrue with far more ordinary research that – although not worthy of a Nobel prize – is essential to the daily pursuit of science. She reminds us of the importance of the kind of person who can reveal dimensions of science other than a singularly great discovery or insight.

Bassi’s passion for physics was, in part, a love affair shared by an entire society that grew up enthralled with the discoveries of the new science. The 18th century ushered in a spectacular world of experiments and instruments that created voids and frictionless worlds, and seemed to channel the very powers of the heavens themselves by generating electricity with machines. Yet Bassi also insisted that to experiment without a proper mathematical and philosophical foundation was to know only half of what one needed to learn to do physics after Newton. Spallanzani, well into his distinguished career as an experimental physiologist, fondly recalled his former mentor several years after her death. “What little I know,” he told Veratti in 1782, “I originally learned from her wise instruction.”

Bassi’s husband and their son Paolo continued the experimental physics course that she had made famous, until constrained finances forced Paolo to sell the instruments in 1818. Well into the 19th century a generation of men could say, as many of them did when asked, “I went to Signora Dottoressa Laura Bassi’s school.” They were all alumni of a singular experiment that produced the only female scientist before the 19th century to have this kind of visible role in the institutionalization of a new scientific discipline. This was due in no small part to Bassi’s tenacious desire to make use of the unheralded opportunity she was given in 1732 when she was celebrated by the entire world as the only woman besides Châtelet to truly understand and explain the science of Newton.

Tracing Laura Bassi today

When Bassi died in February 1778, her colleagues carried her casket in solemn procession to the church of Corpus Domini in Bologna. A marble epitaph created by her husband and four surviving sons can still be seen there today, flanked on its right by the more spectacularly gilded tomb of Luigi Galvani and his wife Lucia Galeazzi. Though the words are faded from centuries of feet marching over this forgotten monument to one of the most interesting female scientists of an earlier era, she has not been entirely ignored. Bassi’s portrait hangs in the University Museum at 33 Via Zamboni, Bologna, where one can also see a 2011 documentary film: Laura Bassi, una vita straordinaria: O de l’aurata luce settemplice, directed by Enza Negroni and produced by Valeria Consolo in consultation with one of the leading Bassi scholars, Marta Cavazza from the University of Bologna, in honour of the 300th anniversary of her birth. Meanwhile, a digital archive created by the Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna in collaboration with Stanford University Libraries has made her family papers available online (http://bassiveratti.stanford.edu). These are fitting tributes to a fascinating scientist whose contributions have been largely forgotten because she so rarely published.