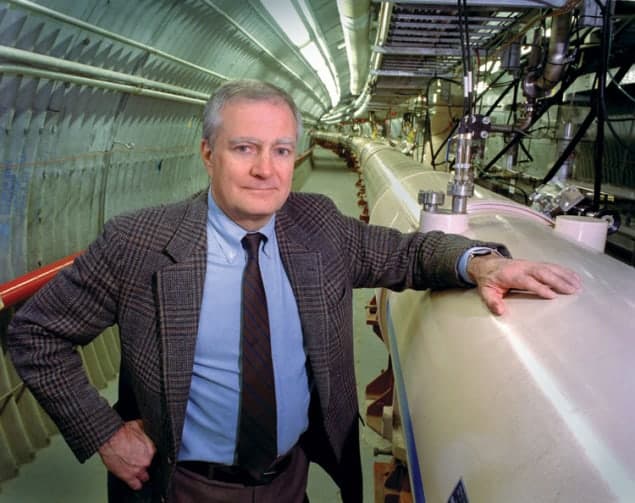

John H Marburger III, lab director and presidential science adviser, died in late July after battling cancer. Robert P Crease discusses the lessons we can learn from this experienced science administrator

John H Marburger III experienced dramatic changes in science policy in his lifetime. For a quarter-century after the Second World War, science was largely protected from public scrutiny and government supervision, with scientists both the actors and judges of their own performances. By the 1980s researchers increasingly worked in an environment where this “fourth wall” – to use a theatre analogy – had disappeared. While researchers continued to receive government funding, they increasingly had to make their actions transparent to regulators and the public, and obey sometimes frustrating rules.

This state of affairs was messy, expensive and inefficient, but Marburger realized that science administrators had no choice but to embrace it. Indeed, he did so himself in his many high-profile appointments – a lesson for future administrators in how to cope.

The bigger story

Marburger was born in Staten Island, New York, in 1941. He graduated with a degree in physics from Princeton University in 1962 and completed a PhD in applied physics at Stanford University in 1967. Marburger joined the University of Southern California (USC), where he became chair of the department of physics in 1972.

Articulate, attentive and respected, Marburger was host of Frontiers in Electronics, a local (pre-recorded) educational TV programme on CBS that aired at 6 a.m. On the morning of 21 February 1973, a magnitude 5.3 earthquake struck California, awakening people throughout the San Fernando Valley. Their first instinct was to turn on the TV. There was Marburger, interviewing an information theorist, not on earthquakes, but about his field. “That episode had a huge audience!” he told me, proudly.

In 1976 Marburger became USC’s dean of arts and sciences. Facing a scandal involving preferential treatment for athletes, USC officials designated Marburger their media spokesperson. The experience taught him valuable lessons about being the public face of an institution. “Be calm, say what you want to say, don’t get complicated, don’t diss anybody,” he once said to me.

As president of Stony Brook University, a position he took up in 1980, Marburger had to co-ordinate advocates of different departments and offices, conjuring policies that inevitably disappointed many but were acceptable to all. His diplomatic skills were sharpened in 1983, when New York governor Mario Cuomo had him chair a fact-finding commission on the controversial Shoreham nuclear-power plant under construction on Long Island. Its diverse collection of members, Marburger knew, would never agree. Still, he managed meetings fairly and patiently, not adjudicating but painting, in his final report, a big picture of the controversy in which all sides could recognize themselves.

The Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), a particle accelerator partly built in Texas but terminated in 1993, was the first big accelerator project on which the government attempted to impose formal procurement and oversight processes. Marburger’s experience as chair of the SSC’s management – University Research Associates – alerted him to a still bigger story: that the government, too, was part of the community scientists had to serve, with its own evolving needs.

Marburger became the go-to person when storm clouds gathered. In 1997 a leak of slightly radioactive water from the spent-fuel pool of a reactor at the Brookhaven National Laboratory led to an uproar. The lab’s manager, Associated Universities Inc., was fired and anti-nuclear activists called for the lab’s closure. Marburger was tapped to be the lab’s new director, and his calm and attentive demeanour did much to resolve the conflict.

White House bound

In 2001 Marburger took the most controversial job of his career when he became science adviser to US President George W Bush. Many in the science community were outraged that he was joining an administration they saw as harmful to science. The psychologist Howard Gardner from Harvard University even labelled him a “prostitute”. “That doesn’t bother me much,” he told me at the time – and I was relieved to hear that final word, revealing him to be not infinitely unflappable, but human after all.

Marburger preferred to be productive rather than get fired, setting out to improve co-ordination between the various government agencies that approve and handle science, and emphasize the brighter side (see Physics World November 2008 pp16–17, print edition only). A genial analogy is that he was fixing an under-utilized office, preparing it for a more appreciative administration to come. A more extreme view is that he was in the morally ambiguous, but defendable, position of a collaborator, trying to do bits of good while working for a superior whose actions he could not alter.

Friends often asked Marburger how, in these roles, he could stand the vociferous criticism from those who failed to appreciate what he was doing. He once pondered that question in his diary. He wrote of building a harpsichord, restoring a vintage car and designing his home using an architectural computer program – all pursuits that juggled complex elements in ways he found soothing. He finally decided his most satisfying pursuit was physics. “Physics has been the main stabilizer of my life,” he wrote.

The critical point

Marburger constantly sought better ways for science administrators to cope with the absence of such a fourth wall. Frustrated at how much science policy is dominated by advocacy, he co-edited a book, The Science of Science Policy, that outlined a framework for this new discipline. He also authored a book about quantum mechanics, Constructing Reality, that is to appear this month, and started a book about his experiences as a science administrator.

In it he would have criticized those who dream of removing decisions about scientific facilities from the public arena. He would have warned that critics would then just turn their fire on that reinstated fourth wall. The only way, in a democracy, is to do what he did at Shoreham, Brookhaven and the White House: tell the story of what is happening in as big a context as possible. If you do so carefully, the wise decision becomes obvious.