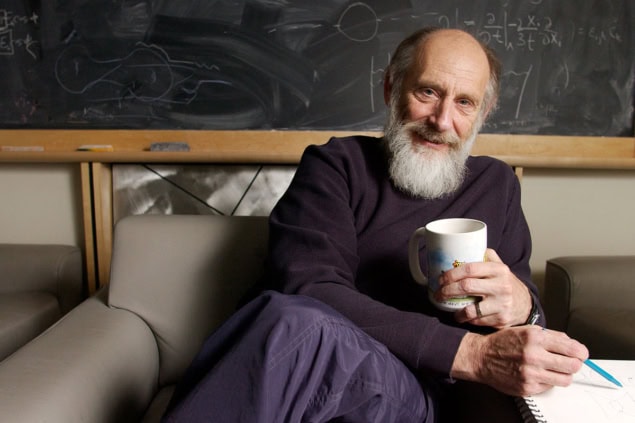

Jon Cartwright speaks to Leonard Susskind about bringing a “theoretical minimum” of real physics to people all over the world through his online courses

One evening a week, Leonard Susskind goes back to basics. In a lecture theatre at Stanford University in California, US, he talks about classical mechanics, quantum theory, relativity and various other topics typical of degree-level physics. But the 100 or so people in the audience do not want a qualification – they are there simply because they enjoy learning.

“I thought I would try it out,” says Susskind, speaking on the phone in his easy New York accent. “And I found it a lot of fun, very stimulating, and very different from teaching a regular university class. People have no interest in degrees, no interest in getting a grade, no interest in getting tested. It’s a very nice way to teach people.”

At 73, Susskind has enjoyed a long career at the forefront of theoretical physics. He is famous for his work on black holes – particularly his “war” with the British theorist Stephen Hawking over the fate of information contained inside them – and for his pioneering work on string theory. Today, as director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics, he is still very active in research, but that has not deterred him from a burgeoning side project: teaching physics to lay-people.

Of course, outreach is a popular occupation among physicists, as the proliferation of science-as-entertainment events and pop-science books testifies. But Susskind’s project is more formal and has a slightly different purpose. In fact, he says his idea came from meeting people who are frustrated to find that the level of physics explanation in pop-science media often falls short of their expectations. “There’s a subset of people who have enough technical background to know that they’re not understanding,” says Susskind. “They have no venue for learning physics in a real way. Textbooks are dry, textbooks are boring, and to learn completely by themselves is not fun.”

Come one, come all

Seeing room for a new type of physics teaching, Susskind started delivering courses he called the Theoretical Minimum. The “minimum” should not imply that the courses are easy. Rather, the term means that Susskind spends the minimum amount of time on a certain topic (for example, classical mechanics) to proceed to the next (for example, quantum mechanics).

“You know, a lot of people from my generation learned quantum field theory from a little skinny book by a [German] gentleman named [Franz] Mandl,” Susskind explains. “It was the only way to get into the subject at the time, because there were no good textbooks. And I have a very distinct memory of having learned easily and quickly from that. I always wanted to try to reproduce that in other subjects, where you really reduce it to the bare minimum.”

Material in the Theoretical Minimum courses was first published in a well-received book of the same name this year, but undoubtedly most students are learning from videos of the lectures. These are available to watch free online via the course website and on YouTube, where the first lecture on classical mechanics has garnered more than 100,000 views so far.

In the sheer number of people it reaches, Susskind’s project is part of a growing trend for so-called massive open online courses, or MOOCs. Similar to distance-learning courses in decades gone by, MOOCs offer university-level education online to those who might otherwise have no access to it. In recent years, MOOC enrollees have skyrocketed. EdX, a MOOC provider run between Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, has registered more than 1.1 million users since it started up last year. “You have simply a better selection and variety of courses for people to take, and definitely there are more people taking them,” says Dan O’Connell, associate director of communications at EdX.

Many universities are looking to further their reach by offering MOOCs through companies such as EdX. But they have not been without criticism. Opponents of MOOCs point to the very high drop-out rates, and believe that they can encourage students to forgo university itself in favour of a (usually) free and flexible online-learning programme. O’Connell, however, points out that data collected through MOOCs can help improve actual university courses.

Making connections

Susskind is largely oblivious to these arguments – indeed, he did not know what a MOOC was until Physics World contacted him for an interview – although he agrees that there is no substitute for on-campus learning. He has no particular goal for the Theoretical Minimum courses, explaining that he simply finds it fun teaching physics to a diverse set of people, who, he claims, are “more responsive” than those studying for degrees. “Some of these people become my friends,” he adds.

I get huge amounts of e-mail, mostly from outside the US

The most gratifying aspect of the project, though, is the response he has had from those watching his courses online. “Once I put the lectures out there, I started getting huge amounts of e-mail, most from outside the US,” he says. “Pakistan, Iran, China.”

“Every time I open my e-mail there’s another five messages thanking me for putting [the videos] out there, telling me about themselves,” he continues. “Lots of kids telling me they’re 15 or 16 years old and they want to be physicists. They don’t have anybody that can teach them.”