Far from being deserted, selectively logged forests provide important refuges for tropical species, sheltering them from severe climate warming. This new finding, reported in Global Change Biology, suggests that these areas could become a vital component of future conservation efforts in the tropics.

Rebecca Senior of the University of Sheffield, UK, together with collaborators from the UK and Malaysia, took detailed temperature measurements of both large and small microhabitats in different plots of forest in Malaysian Borneo. The measurements indicate how well an area shields, or buffers, small-scale habitats from general temperature increases. The team found that the buffering performance of forest selectively logged only 10 years ago was very similar to that of nearby untouched, or primary, forest.

These results highlight the importance of previously-logged forest in conserving the unrivalled biodiversity of the tropics, currently under threat from land-use change. The detrimental impact of wholescale deforestation on local wildlife is well known, but selective logging, where only certain trees are felled, is 20 times more widespread than wholesale conversion.

“Selective logging can be quite intensive, but it will still leave some forest behind,” Senior explains. Once the plant community recovers, and importantly once the canopy closes and shields the ground from the tropical sun, the forest returns to being a haven for animals.

In their study, the researchers conducted a comprehensive survey of each area, characterizing the surrounding vegetation and its community structure. They recorded the general air temperature, while a thermal camera and image analysis techniques were used to measure the temperature of surfaces in the area down to a millimetre scale, the habitat small animals actually experience. Finally, the temperatures of three discrete microhabitats – deadwood, tree holes and leaf litter – were logged for comparison against the overall macroclimate.

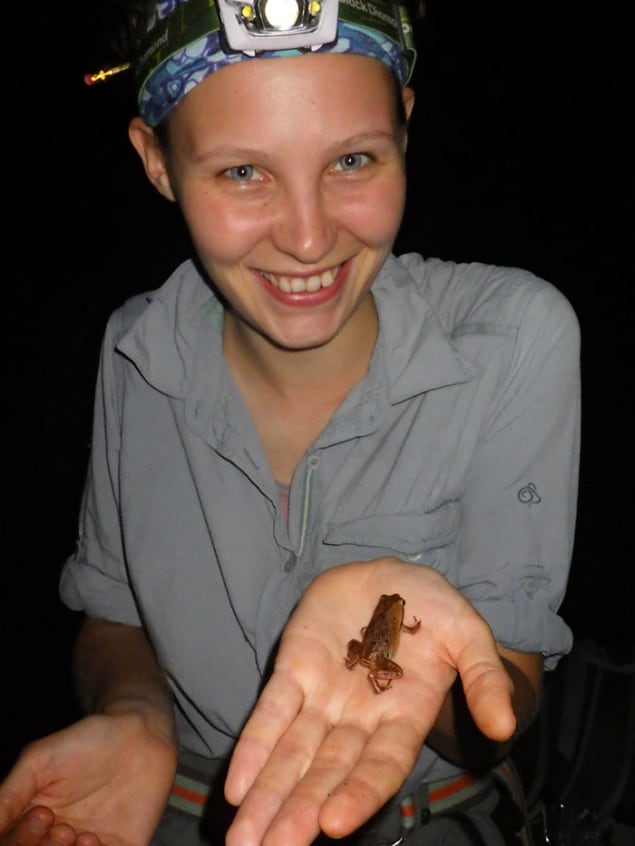

The number and accessibility of microclimate sites are also important to their conservation value. The areas in this study showed no difference in these parameters between logged and primary forest, suggesting that the logged forests can still support the small animals that rely on microclimates. Many of these animals, such as amphibians and invertebrates, are cold-blooded, which means that an ability to escape a wider temperature increase is even more important for their continued survival. These species often require quite a specific environment in which they can thrive, but they also struggle to track temperature zones owing to their own poor dispersal ability or artificial barriers like roads and farmland.

The ability of selectively logged tropical forests to preserve biodiversity adds an important new facet to the challenge conservationists face in maintaining the current richness of life in the tropical regions. Logged forest does show changes: the canopy is closer to the ground and the composition of the leaf litter may be different to primary forest. Yet, irrespective of this, the new work proves how invaluable even a heavily disturbed area can be in conserving the richness of life.