Pablo Jarillo-Herrero tells Hamish Johnston about what happened next after his lab created magic-angle graphene and won the Physics World Breakthrough of the Year award in 2018

In 2018 the nanotechnology community was wowed by two breakthroughs in graphene research made by a team led by Pablo Jarillo-Herrero of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US. Their discoveries led to the rapid emergence of a field called twistronics, which offers a new and very promising technique for adjusting the electronic properties of graphene by rotating adjacent layers of the material.

Calling graphene a wonder material may sound trite, but it is an eminently suitable moniker for a material that continues to amaze condensed-matter physicists like Jarillo-Herrero. I chatted with him about what has happened since his team revealed in 2018 that magic-angle graphene is both a high-temperature superconductor and a Mott insulator.

Graphene is a free-standing sheet of carbon just one atom thick that was first isolated in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov – earning the University of Manchester duo the 2010 Nobel Prize for Physics. Since then, researchers have shown that the material has a range of notable and potentially useful properties ranging from high-electron mobility to great physical strength.

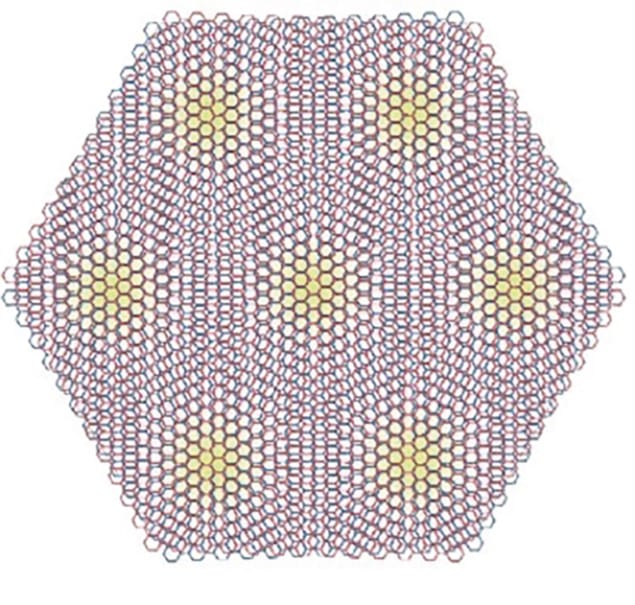

Layers of graphene stack upon each other to make the familiar material graphite. Twisted graphene can be made from two sheets of graphene by rotating the sheets away from the usual stacking angle.

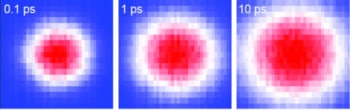

Jarillo-Herrero has been working on twisted graphene since 2009. But the big breakthrough came in 2018, when his team reported how it had stacked two sheets of graphene on top of each other and then twisted the sheets so that the angle between them was 1.1°. At this theoretically predicted “magic angle”, the researchers had expected to observe a range of interesting physics. This is because carbon atoms in the two overlapping graphene crystals create a moiré superlattice.

They were not disappointed and made two very important discoveries. First, they found that magic-angle graphene is a Mott insulator. This is a material that should be a metal but is instead an insulator because of strong interactions (correlations) between electrons.

Then, they added a few extra charge carriers to this Mott-insulator state by applying a small electric field, which turned magic-angle graphene into a superconductor at temperatures below 1.7 K. Despite the low temperature, the proximity to the Mott insulator state and low electron density of the material mean that the material resembles a high-temperature superconductor. So, with a simple twist, Jarillo-Herrero’s team had created a system where small adjustments in terms of angle and electric field creates two iconic states of condensed matter physics – a Mott insulator and a high-temperature superconductor.

It has only been two years since Jarillo-Herrero’s team described its results in two papers, and the work has been cited more than 1200 times. He says that most of the citations are from theorists and that there are now hundreds of theory groups working on the system. It takes longer for experimentalists to learn how to make and characterize magic-angle graphene, but Jarillo-Herrero reckons that there are about 20–25 experimental groups that already have results on the material.

Our discovery is the tip of the iceberg, there is so much more underneath

Pablo Jarillo-Herrero

Despite this huge effort, the physics of magic-angle graphene is still in its infancy and Jarillo-Herrero says that there are many things to study. Beyond superconductivity and the strongly correlated states – both of which occur at low temperatures – he says that there is much to learn about the material at higher temperatures.

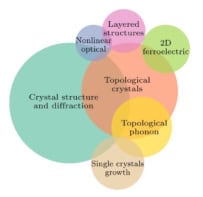

He is also keen to study other 2D materials that can be twisted. One possibility is bilayer graphene on top of bilayer graphene with a twist between the two bilayers. Twisted bilayers are expected to have interesting correlated-electron physics with magnetic properties that are different to those of the original twisted graphene.

Jarillo-Herrero’s team is also looking at twisting materials unrelated to graphene such as 2D superconductors and 2D magnets. There are theoretical predictions, for example, that a special kind of magnetism called moiré magnetism occurs when 2D magnets are twisted on top of each other.

“Our discovery is the tip of the iceberg, there is so much more underneath,” he says, “There is a lot of work for many years to come”.

Jarillo-Herrero is frank and honest about the technological applications of magic-angle materials. “Don’t expect any applications in for 30–40 years – which is the normal timescale for a new material.”

He believes that one technology that could emerge is a superconducting transistor that can be switched between superconducting and normal states. Such devices could be used in cryogenic classical computers, which would run at very low temperatures to avoid the power dissipation problems associated with high-speed silicon processors. Other options include using twisted materials to make superconducting single-photon detectors or superconducting quantum bits for quantum computing.

However, he points out that the technology is still in its infancy in terms of making large and consistent samples of twisted materials.

In the nearer future, Jarillo-Herrero says that magic-angle materials have a wide range of fascinating physics that will be explored. One avenue is quantum simulation, whereby twisted graphene is used as a proxy for a more complicated material such as a high-temperature superconductor.

And, of course, he points out that there should be lots of interesting physics – including topological properties – lurking in twisted graphene itself, which will keep researchers busy for years to come.