Physical exercise plays an important role in controlling disease, including cancer, due to its effect on the human body’s immune system. A research team from the USA and India has now developed a mathematical model to quantitatively investigate the complex relationship between exercise, immune function and cancer.

Exercise is thought to supress tumour growth by activating the body’s natural killer (NK) cells. In particular, skeletal muscle contractions drive the release of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which causes NK cells to shift from an inactive to an active state. The activated NK cells can then infiltrate and kill tumour cells. To investigate this process in more depth, the team developed a mathematical model describing the transition of a NK cell from its inactive to active state, at a rate driven by exercise-induced IL-6 levels.

“We developed this model to study how the interplay of exercise intensity and exercise duration can lead to tumour suppression and how the parameters associated with these exercise features can be tuned to get optimal suppression,” explains senior author Niraj Kumar from the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Impact of exercise intensity and duration

The model, reported in Physical Biology, is constructed from three ordinary differential equations that describe the temporal evolution of the number of inactive NK cells, active NK cells and tumour cells, as functions of the growth rates, death rates, switching rates (for NK cells) and the rate of tumour cell kill by activated NK cells.

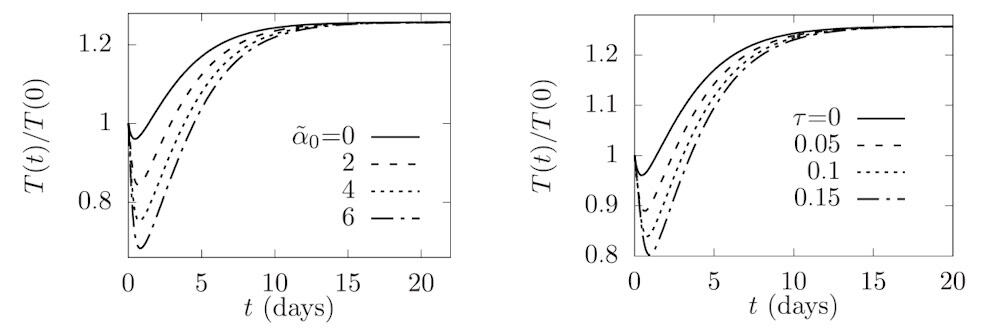

Kumar and collaborators – Jay Taylor at Northeastern University and T Bagarti at Tata Steel’s Graphene Center – first investigated how exercise intensity impacts tumour suppression. They used their model to determine the evolution over time of tumour cells for different values of α0 – a parameter that correlates with the maximum level of IL-6 and increases with increased exercise intensity.

Simulating tumour growth over 20 days showed that the tumour population increased non-monotonically, exhibiting a minimum population (maximum tumour suppression) at a certain critical time before increasing and then reaching a steady-state value in the long term. At all time points, the largest tumour population was seen for the no-exercise case, confirming the premise that exercise helps suppress tumour growth.

The model revealed that as the intensity of the exercise increased, the level of tumour suppression increased alongside, due to the larger number of active NK cells. In addition, greater exercise intensity sustained tumour suppression for a longer time. The researchers also observed that if the initial tumour population was closer to the steady state, the effect of exercise on tumour suppression was reduced.

Next, the team examined the effect of exercise duration, by calculating tumour evolution over time for varying exercise time scales. Again, the tumour population showed non-monotonic growth with a minimum population at a certain critical time and a maximum population in the no-exercise case. The maximum level of tumour suppression increased with increasing exercise duration.

Finally, the researchers analysed how multiple bouts of exercise impact tumour suppression, modelling a series of alternating exercise and rest periods. The model revealed that the effect of exercise on maximum tumour suppression exhibits a threshold response with exercise frequency. Up to a critical frequency, which varies with exercise intensity, the maximum tumour suppression doesn’t change. However, if the exercise frequency exceeds the critical frequency, it leads to a corresponding increase in maximum tumour suppression.

Clinical potential

Overall, the model demonstrated that increasing the intensity or duration of exercise leads to greater and sustained tumour suppression. It also showed that manipulating exercise frequency and intensity within multiple exercise bouts had a pronounced effect on tumour evolution.

These results highlight the model’s potential to guide the integration of exercise into a patient’s cancer treatment programme. While still at the early development stage, the model offers valuable insight into how exercise can influence immune responses. And as Taylor points out, as more experimental data become available, the model has potential for further extension.

Mathematical oncology: exploiting maths for cancer research

“In the future, the model could be adapted for clinical use by testing its predictions in human trials,” he explains. “For now, it provides a foundation for designing exercise regimens that could optimize immune function and tumour suppression in cancer patients, based on the exercise intensity and duration.”

Next, the researchers plan to extend the model to incorporate both exercise and chemotherapy dosing. They will also explore how heterogeneity in the tumour population can influence tumour suppression.