From the APS April Meeting in Denver, Colorado

The April Meeting of the American Physical Society kicked off today with about 1600 particle, nuclear and astrophysicists gathering in Denver, Colorado. I thought I would start the conference by learning a bit more about the other big black-hole news story this month – the 1 April start-up of the upgraded LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors.

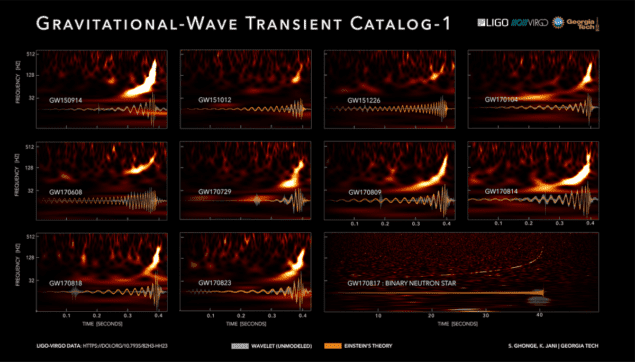

From what I heard in a session called “What we are learning from the population of detected binary black hole mergers“, in less than two weeks the detectors have already bagged two potential black-hole merger events, so the future looks promising.

Indeed, according to Eva Huang of MIT, several black-hole mergers per month should be seen by the detectors — and up to one neutron star merger per month as well.

But what can we learn from the 10 black-hole mergers already spotted, as well as from the many more likely to come?

One important measurement is the rate at which these mergers occur in the universe, which was the subject of a talk by Shasvath Kapadia of the University of Wisconsin — Milwaukee. Knowing this rate should yield a wealth of information about how black holes are formed, how they find themselves in binary systems and how they gradually move close enough together to merge.

Another interesting issue is a black-hole mass gap that is expected to arise from an astrophysical instability that occurs when stars of certain sizes explode as supernovae, which was discussed by Daniel Finstad at Syracuse University. The prediction is that black holes between 50 and 130 solar masses should not be produced by supernovae. The big question is whether LIGO–Virgo has the mass resolution to see this gap?

If you have been following LIGO–Virgo, you know that a merger has already been seen that probably involved a black hole in the gap. Also, many of the observed mergers created black holes with masses well within in the gap. So establishing the existence or otherwise of the gap could be tricky.

And with the first-ever image of a black hole now taken by the Event Horizon Telescope, it looks like it is going to be a very interesting year for black-hole physics.