In 2015 we created several infographics that illustrate the movement of physics Nobel laureates around the world. Our goal was to understand the relationships between high-quality science and migration. Now, with the 2019 Nobel Prize for Physics to be announced on 8 October we have updated the infographics with data from the latest winners.

I have no idea who will bag this year’s prize, but it is a reasonable bet that at least of one of the winners will be an immigrant. Out of 209 physics laureates, we have classified 54 as being immigrants. That is more than 25% and I think you would be hard pressed to find such a high percentage of immigrants and the pinnacle of any field outside of the sciences (or professional football).

What do we mean by an immigrant? This is a tough question, especially in science, where people tend to move around a lot. For the purposes of these infographics, we have used a rather crude definition of an immigrant laureate: someone who died or currently lives in a country other than that of their birth. There is more about how we made the infographics later in this post – but first, what do they tell us?

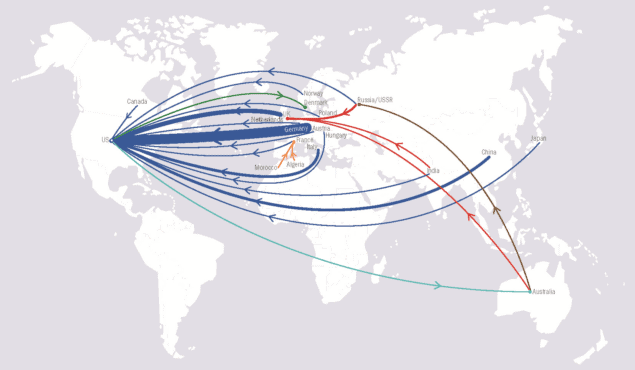

The first infographic (top of this page) paints a geographical picture of migration, with the thickness of the arrowed lines reflecting the numbers of laureates who have migrated from one country to another. There is also a close-up showing movement within Europe.

The most glaring fact is that the US is the clear winner when it comes to inward migration. The country has attracted 33 of these top physicists and only lost two. Another striking observation is the brain drain from Germany, which has lost 14 physicists – 12 of whom went to the US.

The rise of Nazism in Germany accounts for much of this migration. Indeed, it casts a long shadow because the latest person to make the list of laureates who travelled from Germany to the US is Rainer Weiss. He shared the 2017 prize for detecting gravitational waves, but not before fleeing Germany as a child because his father was Jewish and a member of the Communist Party.

All the numbers and the names of our immigrant laureates are shown in the figure “Going with the flow”. It offers a different perspective on migration with a focus on the receiving nations, which appear on the right.

Second place in terms of influx is France, which has been very good at attracting talent from its French-speaking neighbours. The UK has broken even, gaining as many laureates (five) as it has lost. The latest newcomers to the UK are USSR-born Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, who bagged the 2010 prize. However, Novoselov has just accepted a position in Singapore (while maintaining his affiliation with the University of Manchester), so we may have to update his flow next year.

While we think these infographics do a good job of capturing migration patterns of Nobel winners, they are not perfect. Indeed, when compiling these data we often struggled with whom to include as an immigrant.

Coming home

For example, the 2016 laureate David Thouless was born in the UK, did his prize-winning research in the US, but then returned to his native country five years before his death in April. As a result, we did not count Thouless as an immigrant, although some might argue that he was an immigrant when he did his Nobel-winning work. The same could be said of Canadian Donna Strickland (2018). She won for work done at an American university but now lives in Canada, where she has spent most of her professional career.

Considering where the Nobel-winning work was done introduces another problem. Enrico Fermi – who left Italy for the US shortly after winning his prize – would then not be counted as an immigrant, despite the important contributions he subsequently made to physics in his adopted American homeland.

Shifting borders also posed a challenge when compiling and presenting these data. Some parts of Europe have changed countries three of four times during the 20th century, throwing up some strange instances. One of the trickiest calls was Alfred Kastler, who was born in Alsace in 1902. It was then part of Germany but became part of France in 1918. Kastler pursued his career in France, where he died in 1984, and despite his Germanic surname and apparent penchant for writing poetry in German, we did not include him as an immigrant.

We’ve done our best to navigate through the shifting borders of Europe (and the Indian subcontinent), but if you disagree with any of our data or think we have forgotten someone, please let us know.

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more.