Deep brain stimulation (DBS) – in which electrodes implanted in the brain send electrical signals to areas that control movement – is increasingly employed to treat symptoms of movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor or dystonia. It is also used in epilepsy and is under investigation as a potential treatment for traumatic brain injury, addiction, dementia, depression and several other conditions.

Patients with implanted electrodes often undergo brain MRI, for example to guide electrode placement, investigate DBS outcomes or evaluate implantation-related abnormalities. DBS electrodes are generally made from thin-film platinum or iridium oxide. However, such metal-based electrodes are affected by the magnetic fields of the MR scanner, and can cause image artefacts, move or vibrate, or even generate heat.

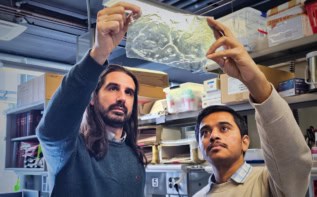

To tackle these problems, San Diego State University (SDSU) engineers have created a glassy carbon microelectrode for use instead of the metal version. Working in collaboration with researchers at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, they have now shown that the new electrode does not react to MRI scanning, making it a safer option for DBS (Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10.1038/s41378-019-0106-x).

“Our lab testing shows that, unlike the metal electrode, the glassy carbon electrode does not get magnetized by the MRI, so it won’t irritate the patient’s brain,” explains first author Surabhi Nimbalkar.

The glassy carbon electrodes, first developed in 2017 at SDSU, are designed to last longer in the brain without deterioration. The researchers previously demonstrated that while metal electrodes degrade after 100 million electrical impulse cycles, the glassy carbon material survived 3.5 billion cycles. Another benefit is that glassy carbon electrodes can read both chemical and electrical signals from the brain.

“It’s supposed to be embedded for a lifetime, but the issue is that metal electrodes degrade, so we’ve been looking at how to make it last a lifetime,” says senior author Sam Kassegne. “Inherently, the carbon thin-film material is homogenous so it has very few defective surfaces. Platinum has grains of metal, which become the weak spots vulnerable to corrosion.”

In their latest study, Kassegne and colleagues fabricated probes made from glassy carbon and thin-film platinum microelectrodes supported on a polymer substrate. They placed the probes in a brain-tissue-mimicking agarose phantom and imaged them in a 3 T MRI scanner using clinical MRI sequences.

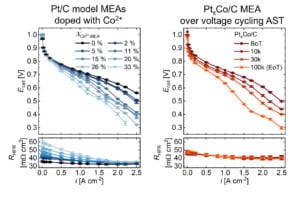

The researchers found that, because of their low magnetic susceptibility and lower conductivity, the glassy carbon microelectrodes caused almost no susceptibility shift artefacts and no eddy-current-induced artefacts compared with the platinum microelectrodes. Tests in a high-field (11.7 T) magnet exhibited similar findings.

The team also used a novel instrument developed at KIT to precisely measure gradient-induced vibrations in the electrodes during 1.5 T MRI. Both the platinum and glassy carbon microelectrode samples had vibration amplitudes below the limit of detection (indistinguishable from that of non-conductive PMMA plates).

Theoretical analysis, however, revealed that while the platinum microelectrode was at the limit of detection, the glassy carbon microelectrode had an approximately 40-fold weaker response. The team also note that gradient-induced vibration scales to the power of four with implant radius, so for larger electrodes, the smaller conductance of glassy carbon will be advantageous.

Finally, to examined induced currents in the two microelectrode types, the researchers fabricated glassy carbon and platinum ring electrodes supported on a silicon wafer. Induced currents measured with a 1 Ω resistor indicated that induced current in glassy carbon was at least a factor of 10 less than in the platinum sample.

The researchers conclude that glassy carbon microelectrodes demonstrated superior MR compatibility to standard thin-film platinum microelectrodes, experiencing no considerable vibration amplitudes, minimally induced currents and generating almost no image artefacts. While they did not examine RF-induced heating in this study, the lack of RF-induced eddy currents (a large source of heating) in glassy carbon microelectrodes suggests that they will also be superior to platinum in this aspect.

With lab testing completed, Kassegne’s clinical collaborators will now test the glassy carbon electrode in patients, while Nimbalkar and Kassegne plan to test different forms of carbon for use in future electrodes.