Controversial new historical evidence suggests that German physicists built and tested a nuclear bomb during the Second World War. Rainer Karlsch and Mark Walker outline the findings and present a previously unpublished diagram of a German nuclear weapon

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the American nuclear attack on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan in August 1945 were the fruit of a herculean wartime effort by the American, British and émigré scientists involved in the Manhattan Project. They had to overcome great obstacles and were only able to test their first atomic bomb after Germany surrendered in May of that year. The main motivation for these scientists when the project began in 1941 was the possibility that they were engaged in a race with their German counterparts to harness nuclear fission for war.

Even Albert Einstein had been involved, signing a letter to President Roosevelt in 1939 urging that the US take nuclear weapons seriously. And in December 1943 the Danish physicist Niels Bohr visited Los Alamos – the home of the Manhattan Project – to offer both scientific and moral support. But when the war was over, it was clear that the Germans did not have atomic bombs like those used against Japan.

The German “uranium project” – which had been set up in 1939 to investigate nuclear reactors, isotope separation and nuclear explosives – amounted to no more than a few dozen scientists scattered across the country. Many of them did not even devote all of their time to nuclear-weapons research. The Manhattan Project, in contrast, employed thousands of scientists, engineers and technicians, and cost several billion dollars.

Not surprisingly, historians have concluded that Germany was not even close to building a working nuclear device. However, newly discovered historical material makes this story more complicated – and much more interesting.

Germany and the bomb: a turbulent tale

Our understanding of the German nuclear-weapons project during the Second World War has changed over time because important new sources of information keep turning up. For example, in 1992 the British government released transcripts of secretly recorded conversations between 10 German scientists who had been interned at Farm Hall near Cambridge in 1945. With the exception of Max van Laue, all the scientists – Erich Bagge, Kurt Diebner, Walther Gerlach, Otto Hahn, Paul Harteck, Werner Heisenberg, Horst Korsching, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz – had been involved in the uranium project. What was most interesting was the surprise with which the scientists greeted the news that Hiroshima had been bombed. Ironically, at the end of the war German scientists had been convinced that they were ahead of the Allies in the race for nuclear energy and nuclear weapons.

Further intriguing material appeared in 2002 when the Niels Bohr Archives in Copenhagen released drafts of letters that had been written by Bohr in the late 1950s about a visit to occupied Denmark by Heisenberg and von Weizsäcker in September 1941. After the war, the two German physicists claimed that they had merely gone to Copenhagen to assist Bohr and enlist his help in their efforts to forestall all nuclear weapons. But in the letters, Bohr denied that their actions or motivations had been so noble. The intrigue surrounding the visit has been well dramatized in Michael Frayn’s play Copenhagen.

We now have an extra twist to the tale with new documents that were recently discovered in Russian archives, including papers from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics in Berlin. There are four particularly notable items among this material: an official report written by von Weizsäcker after a visit to Copenhagen in March 1941; a draft patent application written by von Weizsäcker sometime in 1941; a revised patent application in November of that year; and the text of a popular lecture given by Heisenberg in June 1942.

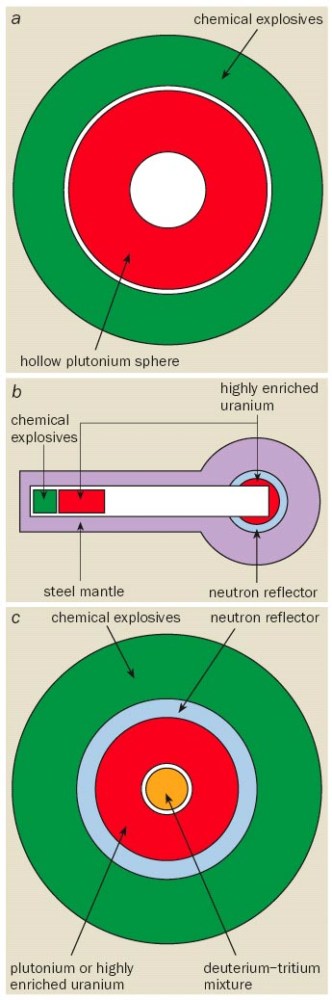

One of us (RK) has used these documents – as well as many other sources – as the basis of a new book Hitlers Bombe. The book, which was published in March, prompted a heated debate about how close Germany was to acquiring nuclear weapons and how significant these weapons were (see Physics World April 2005 p7). Working with the journalist Heiko Petermann, RK discovered that a group of German scientists had carried out a hitherto-unknown nuclear-reactor experiment and tested some sort of a nuclear device in Thüringia, eastern Germany, in March 1945. According to eyewitness accounts given at the end of that month and two decades later, the test killed several hundred prisoners of war and concentration-camp inmates. Although it is not clear if the device (figure 1) worked as intended, it was designed to use nuclear fission and fusion reactions. It was, therefore, a nuclear weapon.

Following the publication of Hitlers Bombe, another document has turned up from a private archive. Written immediately after the end of the war in Europe, the undated document contains the only known German drawing of a nuclear weapon (figure 2).

What did German scientists know?

Over the years, several authors have concluded that Heisenberg and his colleagues did not understand how an atomic bomb would work. These authors include the physicist Samuel Goudsmit, who in 1947 published the results of a US Army investigation – entitled Alsos – into Germany’s bomb effort. The historian Paul Lawrence Rose came to the same conclusion in his 1998 book Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project 1939-1945. These critics argue that the German scientists did not understand the physics of a nuclear-fission chain reaction, in which fast neutrons emitted by a uranium-235 or plutonium nucleus trigger further fission reactions. Both Goudsmit and Rose also say the Germans failed to realize that plutonium can be a nuclear explosive.

These criticisms of the Germans’ scientific incompetence are apparently reinforced by the Farm Hall conversations, which reveal that Heisenberg initially responded to the news of Hiroshima with a flawed calculation of critical mass, although within a few days he had improved it and provided a very good estimate. However, there was other evidence that, no matter how Heisenberg responded at Farm Hall, he and his colleagues understood that atomic bombs would use fast-neutron chain reactions and that both plutonium and uranium-235 were fissionable materials.

For example, in February 1942 the German army officials who were responsible for weapons development described the progress of the uranium project in a report entitled “Energy production from uranium”. This overview, which was discovered in the 1980s, drew upon all classified material from Hahn, Harteck, Heisenberg and the other scientists working on the project. The report concluded that pure uranium-235 – which forms just 0.7% of natural uranium, the rest being non-fissionable uranium-238 – would be a nuclear explosive a million times more powerful than conventional explosives. It also argued that a nuclear reactor, once operating, could be used to make plutonium, which would be an explosive of comparable force. The critical mass of such a weapon would be “around 10-100 kg”, which was comparable to the Allies’ estimate from 6 November 1941 of 2-100 kg that is recorded in the official history of the Manhattan Project – the so-called Smyth report.

Von Weizsäcker’s draft patent application of 1941, which is perhaps the most surprising find from the new Russian documents, makes it crystal clear that he did indeed understand both the properties and the military applications of plutonium. “The production of element 94 [i.e. plutonium] in practically useful amounts is best done with the ‘uranium machine’ [nuclear reactor],” the application states. “It is especially advantageous – and this is the main benefit of the invention – that the element 94 thereby produced can easily be separated from uranium chemically.”

Von Weizsäcker also makes it clear that plutonium could be used in a powerful bomb. “With regard to energy per unit weight this explosive would be around ten million times greater than any other [existing explosive] and comparable only to pure uranium 235,” he writes. Later in the patent application, he describes a “process for the explosive production of energy from the fission of element 94, whereby element 94…is brought together in such amounts in one place, for example a bomb, so that the overwhelming majority of neutrons produced by fission excite new fissions and do not leave the substance”.

This is nothing less than a patent claim on a plutonium bomb.

On 3 November 1941 the patent application was resubmitted with the same title: “Technical extraction of energy, production of neutrons, and manufacture of new elements by the fission of uranium or related heavier elements”. This submission differed in two significant ways. First, the patent was now filed on behalf of the entire Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, instead of just von Weizsäcker. Second, every mention of nuclear explosive or bomb had been removed.

The removal of any reference to weapons could reflect the change of fortunes in the Second World War: in November 1941 a quick German victory no longer appeared as certain as it had done earlier in the year. Another possible explanation is that von Weizsäcker and his colleagues had a change of heart – perhaps their initial enthusiasm for the military applications of nuclear fission had cooled. This would support Heisenberg’s and von Weizsäcker’s post-war claims that they had visited Bohr in September 1941 because they were ambivalent about working on nuclear weapons. Perhaps the most forceful exponent of this thesis is Thomas Powers in his 1993 book Heisenberg’s War.

But another of the new Russian documents – von Weizsäcker’s report on his visit to Copenhagen in spring 1941 – suggests that, at least at that time, he was enthusiastic about the uranium work. Indeed, we know that, after the war, scientists from Bohr’s institute accused Heisenberg and von Weizsäcker of acting as German spies when they came to Copenhagen. There may at least be some truth to this because in March 1941, when Germany had not yet invaded the Soviet Union and victory appeared likely, von Weizsäcker reported the following to the Army.

“The technical extraction of energy from uranium fission is not being worked on in Copenhagen. They know that in America Fermi has started research into these questions in particular; however, no more news has arrived since the beginning of the war. Obviously Professor Bohr does not know that we are working on these questions; of course, I encouraged him in this belief…The American journal Physical Review was complete in Copenhagen up to the January 15, 1941 issue. I have brought back photocopies of the most important papers. We arranged that the German Embassy will regularly photocopy [make photographs of] the issues for us.”

The spotlight turns to Diebner

RK’s book Hitlers Bombe draws upon what was already known about the German wartime work on nuclear reactors and isotope separation, and uses documents from Russian archives, oral history and industrial archaeology to open up a new chapter in the history of German nuclear weapons. For most of the war, there were two competing groups working on nuclear reactors: a team under the Army physicist Kurt Diebner in Gottow near Berlin; and scientists directed by Werner Heisenberg in Leipzig and Berlin.

Whereas the experiments under Heisenberg used alternating layers of uranium and moderator, Diebner’s team developed a superior 3D lattice of uranium cubes embedded in moderator. Heisenberg never gave Diebner and the scientists working under him the credit they were due, but the Nobel laureate did take up Diebner’s design for the last experiment carried out in Haigerloch in south-west Germany. RK now reveals that Diebner managed to carry out one last experiment in the last months of the war. The exact details of the experiment are unclear. After a series of measurements had been taken, Diebner wrote a short letter to Heisenberg on 10 November 1944 that informed him of the experiment and hinted that there had been problems with the reactor. Unfortunately, no more written sources have been found relating to this final reactor experiment in Gottow. Industrial archaeology done at the site during 2002 and 2003 suggests that this reactor sustained a chain reaction – if only for a short period of time – and may have ended in an accident.

In 1955 Diebner submitted a patent application for a new type of “two-stage” reactor that could breed plutonium. An internal section would use enriched uranium to achieve a self-sustaining chain reaction, while a much larger external section would surround the internal reactor and run at a subcritical level. Plutonium could then be removed from internal section. It appears likely that Diebner’s 1955 patent application drew upon his last wartime experiment.

More surprising, if not shocking, is another revelation in RK’s book: a group of scientists under Diebner built and tested a nuclear weapon with the strong support of both Walther Gerlach – an experimental nuclear physicist who by 1944 was in charge of the uranium project for the Reich Research Council. (Hahn, Heisenberg, von Weizsäcker and most of the better-known scientists in the uranium project apparently were not informed about this weapon.) This device was designed to use fission reactions, but it was not an “atomic” bomb like the weapons used against Nagasaki and Hiroshima (figures 1a and b). And although it was also designed to exploit fusion reactions, it was nothing like the “hydrogen” bombs tested by the US and the Soviet Union in the 1950s.

Instead, conventional high explosives were formed into a hollow shape, rather than a solid mass, to focus the energy and heat from the explosion to one point inside the shell (figure 1c). Small amounts of enriched uranium, as well as a source of neutrons, were combined with a deuterium-lithium mixture inside the shell. This weapon would have been more of a tactical than a strategic weapon, and could not have won the war for Hitler in any case. It is not clear how successful this design was and whether fission and fusion reactions were provoked. But what is important is the revelation that a small group of scientists working in the last desperate months of the war were trying to do this.

Blueprint for a bomb

Shortly after the end of the war in Europe, an unknown German or Austrian scientist wrote a report that describes work on nuclear weapons during the war. This report, which RK discovered after Hitlers Bombe was published, contains both accurate information and less accurate speculation about nuclear weapons, and may well include some information from the Manhattan Project – the word “plutonium” is used, for example. Unfortunately, the title page is not included and there is no other evidence of who composed it. However, this individual does not appear to have been a member of either the mainstream German uranium project or the group working under Diebner.

What the report does demonstrate is that the knowledge that uranium could be used to make powerful new weapons was fairly widespread in the German technical community during the war, and it contains the only known German diagram of a nuclear weapon (figure 2). This diagram is schematic and is far removed from a practical blueprint for an “atomic bomb”. The unknown author also mentions a critical mass of slightly more than 5 kg for a plutonium bomb. This estimate is fairly accurate, because the use of a tamper to reflect neutrons back into the plutonium would cut the critical mass by a factor of two. Moreover, this estimate is particularly significant because such detailed information was not included in the Smyth report.

The new report is also interesting because it makes clear that German scientists had worked intensively on theoretical questions concerned with the construction of a hydrogen bomb. Two additional sources con- firm this. The papers of Erich Schumann, director of the Army’s weapons-research department, include many documents and theoretical calculations of nuclear fusion. The Viennese physicist Hans Thirring also discussed this topic in his book The History of the Atomic Bomb, which was published in the summer of 1946.

Not the last word

Historians, scientists and others have debated for decades whether Heisenberg and von Weizsäcker wanted to build atomic bombs.Taken together, the new revelations change our picture of German nuclear weapons. None of this new information supports in any way either the interpretation of Heisenberg and his colleagues as resistance fighters (Powers) or as incompetents with Nazi sympathies (Rose).

However, these new documents and RK’s revelations do place Heisenberg and von Weizsäcker in a different context by making their ambivalence about nuclear weapons much clearer. Although they continued to work on nuclear reactors and isotope separation, and dangled the prospect of nuclear weapons in front of powerful men in the Nazi state, they did not try as hard as they could to create nuclear weapons for Hitler’s regime. Other scientists were doing that, notably Walther Gerlach,Kurt Diebner and the researchers working under him.

It would be rash indeed to believe that this is the last word on the matter. The German atomic bomb is like a zombie: just when we think we know what happened, how and why, it rises again from the dead.

Box 1: Heisenberg’s role

During the Second World War, Werner Heisenberg was one of the most influential scientists in Germany and its leading theoretical physicist. He had won a Nobel prize for his work on quantum mechanics and the uncertainty principle, had become one of the youngest full professors in Germany when he began teaching at the University of Leipzig, and in 1942 at the age of 40 was appointed director of the prestigious Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics as well as professor at the University of Berlin.

However, in the early years of the Third Reich, Heisenberg had been attacked by his fellow Nobel laureate Johannes Stark in an SS publication for being a “white Jew” and “Jewish in spirit”. A subsequent investigation by the SS ended in 1939 with his public and political rehabilitation. The result was that, by 1942, Heisenberg enjoyed the support of influential figures in the Nazi regime, including the armaments minister Albert Speer, as well as the industrialist Albert Vögler, who was president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society.

In February 1942 Heisenberg gave a popular lecture to an influential audience of politicians, bureaucrats, military officers and industrialists. At the time, the future of Germany’s uranium project was in doubt because the Army was only interested in weapons that could be delivered in time to influence the outcome of the war. As we know from a transcript of the talk, which was discovered by the historian David Irving in the 1960s, Heisenberg emphasized both the potential of nuclear weapons and how difficult it would be to make them. His conclusion was clear.

“1) Energy generation from uranium fission is undoubtedly possible, provided the enrichment of isotope uranium-235 is successful. Isolating uranium-235 would lead to an explosive of unimaginable potency. 2) Common uranium can also be exploited to generate energy when layered with heavy water. In a layered arrangement these materials can transfer their great energy reserves over a period of time to a heat-engine. It thus provides a means of storing very large amounts of energy that are technically measurable in relatively small quantities of substances. Once in operation, the machine can also lead to the production of an incredibly powerful explosive.”

However, by the summer of 1942, the uranium project had been transferred from the German Army to the civilian Reich Research Council and the German uranium-project scientists once again enjoyed secure institutional support. In June of that year Heisenberg gave a lecture at the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Berlin before Speer and other military and industrial leaders of the Nazi state. The lecture has become famous because of the story that Heisenberg responded to a question about the size of an atomic bomb by saying that it would be about as big as a pineapple.

This anecdote was first reported in Irving’s 1968 book The Virus House, but a transcript of the talk had never been found. However, it has now been discovered in the new Russian documents. The text of the June lecture – entitled “The work on uranium problems” – differs significantly from the February talk. Heisenberg begins by mentioning the discovery of nuclear fission in 1939, noting that interest in this new development had been “exceptionally great”, especially in the US. “A few days after the discovery,” he notes, “American radio provided extensive reports and half a year later a large number of scientific papers had appeared on this subject.”

Heisenberg continues by describing Germany’s work on isotope separation and nuclear reactors since the start of the war, cautioning that “naturally a series of scientific and practical problems will have to be cleared up before the technical goals can be realized”. Mid-way through the talk, Heisenberg makes his only mention of nuclear weapons in a rather understated way. “Given the positive results achieved up until now,” he says, “it does not appear impossible that, once an uranium burner has been constructed, we will one day be able to follow the path revealed by von Weizsäcker to explosives that are more than a million times more effective that those currently available.”

But even if that did not happen, the nuclear reactor would have an “almost unlimited field of technical applications”. These include boats and even planes that could travel long distances on small amounts of fuel, as well as new radioactive substances that could be useful for many scientific and technical problems. Heisenberg concludes by saying that new discoveries of “the greatest significance for technology” will be made “in the next few years”.

Since the Germans knew that “many of the best laboratories” in America were working on this problem, they could hardly afford “not to follow these questions”, Heisenberg points out. Even if “most such developments take a long time”, they had to reckon with the possibility that – if the “war with America lasted for several years” – the “technical realization of atomic nuclear energies” might “play a decisive role in the war”.

Heisenberg was right about that, of course. But fortunately for him and his countrymen, the first atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki instead of Frankfurt and Berlin.

Box 2: A timeline to the bomb

January 1933 Nazis come to power in Germany

December 1938 Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz

Strassmann discover nuclear fission in

uranium

2 August 1939 Einstein warns President Roosevelt of

dangers of an atomic bomb

1 September 1939 Germany invades Poland and launches

”uranium project”

3 September 1939 Britain and France declare war on Germany

1941 Von Weizsäcker files a draft patent

application that refers to a plutonium bomb

March 1941 Von Weizsäcker visits Bohr in Copenhagen

June 1941 Germany invades Soviet Union

September 1941 Von Weizsäcker visits Bohr again, this time

with Heisenberg

6 December 1941 Manhattan Project begins in Los Alamos

7 December 1941 Japan attacks Pearl Harbour

8 December 1941 US enters Second World War

February/June 1942 Heisenberg gives popular lectures on

nuclear weapons

December 1943 Bohr visits Los Alamos

March 1945 Germany tests a nuclear device in

Thüringia, eastern Germany

7 May 1945 Germany surrenders

16 July 1945 Trinity test – world’s first atomic blast

6 August 1945 US bombs Hiroshima

9 August 1945 US bombs Nagasaki

14 August 1945 Japan surrenders