Geophysicists in the US are proposing a new magnetic field generated in the Earth’s core, the existence of which could help us understand why our planet’s magnetic moment has flipped several times in the past.

By measuring ancient field patterns frozen into the volcanic rocks of West Eifel in Germany and Tahiti in French Polynesia, Kenneth Hoffman of California Polytechnic University and Brad Singer of the University of Wisconsin–Madison have recorded the first data to suggest that the Earth’s dipolar magnetic field is accompanied by a second magnetic field with a distinct origin in the Earth’s core (Science 321 1800).

Although geophysicists know that the Earth’s magnetic field is complex, most think that it is based on one field with a single source. “Many see the field as a unified thing,” says Hoffman, “but if these two field sources are mostly independent, then when they interact in a certain manner, that may start the reversal process.”

A natural tape recorder

The Earth’s magnetic field can reverse polarity in just 10,000 years, during which time its intensity reduces to a fraction of its normal value. Geologists know this because magnetic minerals, which align with the prevailing magnetic field, get frozen into lava as it cools into volcanic rock, forming a “palaeomagnetic record”.

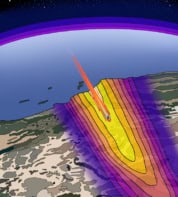

At the Earth’s surface the magnetic field is dominated by an axial dipole component, and it is with this that a compass needle aligns. But there are also weaker, non-axial dipole (NAD) components that are frozen into the palaeomagnetic record.

At present, there is no general theory to explain the origin of the Earth’s magnetic field but it is believed to originate from convection in the fluid, outer sector of Earth’s iron-rich core. Since the 1950s there has been a suggestion that the dipole field is generated at a deeper location than the NAD components but until now there has been no data to support this claim.

Almost reversals

Hoffman and Singer analysed palaeomagnetic data from antipodal locations in Germany and French Polynesia covering the 780,000 years since the last reversal. By measuring the ratio of argon–40 to argon–39 isotopes to date the rocks, they found a number of “events” when the dipole field intensity had reduced, threatening a reversal before returning to its normal state.

Surprisingly, after analysing these palaeomagnetic events along with recordings from the past 400 years, Hoffman and Singer found that the NAD field has remained virtually unchanged over the past 780,000 years. They believe this dichotomy results from the fields having two separate sources: the dipole field comes from convective flow deep within the liquid iron core, while the NAD component comes from the very top of the outer core. Here, physical changes in the overlying mantle rock, which occur over timescales of millions of years, govern the patterns of convection.

The mechanism of polarity reversal has puzzled earth scientists for many years but Hoffman believes new theories and models should consider the interaction between these two physically distinct layers in the Earth’s core.

David Gubbins, an Earth scientist at Leeds University who has also published research linking the lower mantle with convection patterns in the outer core, warns that the US researchers have only used data taken from two sites. However, Hoffman told physicsworld.com that he and Singer intend to develop their research by broadening their analysis to volcanic rocks in other parts of the world.