Mike Follows reviews World Without End: an Illustrated Guide to the Climate Crisis by Jean-Marc Jancovici and Christophe Blain, translated by Edward Gauvin

Comics are regarded as an artform in France, where they account for a quarter of all book sales. Nevertheless, the graphic novel World Without End: an Illustrated Guide to the Climate Crisis was a surprise French bestseller when it first came out in 2022. Taking the form of a Socratic dialogue between French climate expert Jean-Marc Jancovici and acclaimed comic artist Christophe Blain, it’s serious, scientific stuff.

Now translated into English by Edward Gauvin, the book follows the conventions of French-language comic strips or bandes dessinées. Jancovici is drawn with a small nose – denoting seriousness – while Blain’s larger nose signals humour. The first half explores energy and consumption, with the rest addressing the climate crisis and possible solutions.

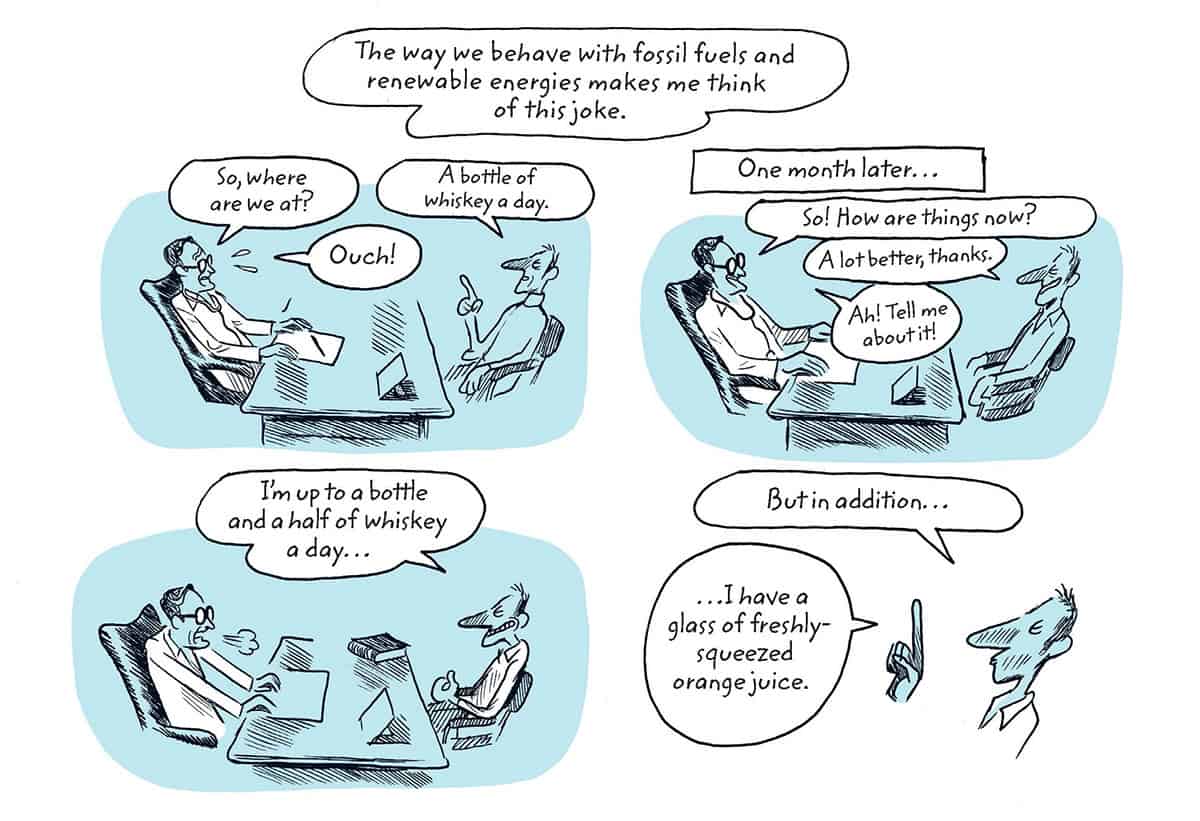

Overall, this is a Trojan horse of a book: what appears to be a playful comic is packed with dense, academic content. Though marketed as a graphic novel, it reads more like illustrated notes from a series of sharp, provocative university lectures. It presents a frightening vision of the future and the humour doesn’t always land.

The book spans a vast array of disciplines – not just science and economics but geography and psychology too. In fact, there’s so much to unpack that, had I Blain’s skills, I might have reviewed it in the form of a comic strip myself. The old adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words” has never rung more true.

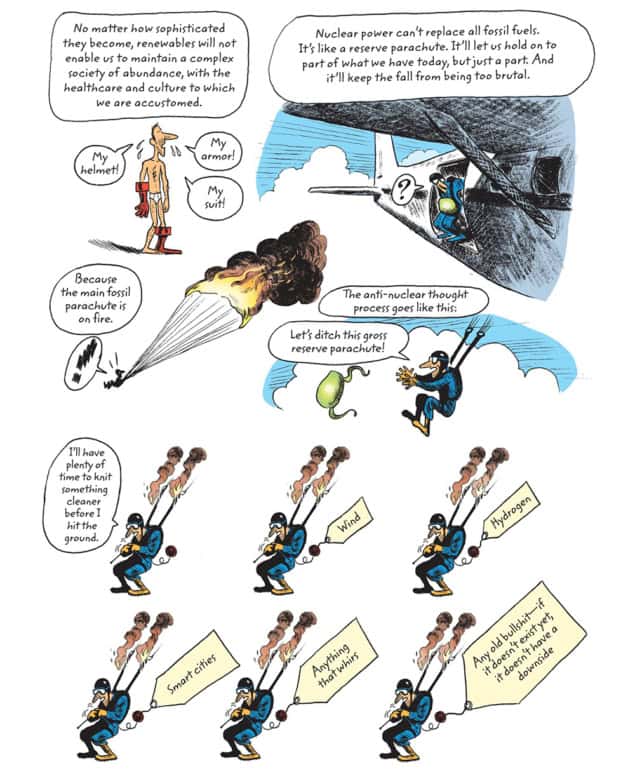

Absurd yet powerful visual metaphors feature throughout. We see a parachutist with a flaming main chute that represents our dependence on fossil fuels. The falling man jettisons his reserve chute – nuclear power – and tries to knit an alternative using clean energy, mid-fall. The message is blunt: nuclear may not be ideal, but it works.

World Without End is bold, arresting, provocative and at times polemical

The book is bold, arresting, provocative and at times polemical. Charts and infographics are presented to simplify complex issues, even if the details invite scrutiny. Explanations are generally clear and concise, though the author’s claim that accidents like Chernobyl and Fukushima couldn’t happen in France smacks of hubris.

Jancovici makes plenty of attention-grabbing statements. Some are sound, such as the notion that fossil fuels spared whales from extinction as we didn’t need this animal’s oil any more. Others are dubious – would a 4 °C temperature rise really leave a third of humanity unable to survive outdoors?

But Jancovici is right to say that the use of fossil fuels makes logical sense. Oil can be easily transported and one barrel delivers the equivalent of five years of human labour. A character called Armor Man (a parody of Iron Man) reminds us that fossil fuels are like having 200 mechanical slaves per person, equivalent to an additional 1.5 trillion people on the planet.

Fossil fuels brought prosperity – but now threaten our survival. For Jancovici, the answer is nuclear power, which is perhaps not surprising as it produces 72% of electricity in the author’s homeland. But he cherry picks data, accepting – for example – the United Nations figure that only about 50 people died from the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

While acknowledging that many people had to move following the disaster, the author downplays the fate of those responsible for “cleaning up” the site, the long-term health effects on the wider population and the staggering economic impact – estimated at €200–500bn. He also sidesteps nuclear-waste disposal and the cost and complexity of building new plants.

While conceding that nuclear is “not the whole answer”, Jancovici dismisses hydrogen and views renewables like wind and solar as too intermittent – they require batteries to ensure electricity is supplied on demand – and diffuse. Imagine blanketing the Earth in wind turbines.

Still, his views on renewables seem increasingly out of step. They now supply nearly 30% of global electricity – 13% from wind and solar, ahead of nuclear at 9%. Renewables also attract 70% of all new investment in electricity generation and (unlike nuclear) continue to fall in price. It’s therefore disingenuous of the author to say that relying on renewables would be like returning to pre-industrial life; today’s wind turbines are far more efficient than anything back then.

Beyond his case for nuclear, Jancovici offers few firm solutions. Weirdly, he suggests “educating women” and providing pensions in developing nations – to reduce reliance on large families – to stabilize population growth. He also cites French journalist Sébastien Bohler, who thinks our brains are poorly equipped to deal with long-term threats.

Graphic novel tells a tale of catastrophe and complexity

But he says nothing about the need for more investment in nuclear fusion or for “clean” nuclear fission via, say, liquid fluoride thorium reactors (LFTRs), which generate minimal waste, won’t melt down and cannot be weaponized.

Perhaps our survival depends on delaying gratification, resisting the lure of immediate comfort, and adopting a less extravagant but sustainable world. We know what changes are needed – yet we do nothing. The climate crisis is unfolding before our eyes, but we’re paralysed by a global-scale bystander effect, each of us hoping someone else will act first. Jancovici’s call for “energy sobriety” (consuming less) seems idealistic and futile.

Still, World Without End is a remarkable and deeply thought-provoking book that deserves to be widely read. I fear that it will struggle to replicate its success beyond France, though Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows – a Cold War graphic novel about nuclear annihilation – was once a British bestseller. If enough people engaged with the book, it would surely spark discussion and, one day, even lead to meaningful action.

- 2024 Particular Books £25.00hb 196pp