In Physics World‘s previous special section on graduate careers, back in March, we revealed how a physics degree opens a lot of doors, but no main one. To get a glimpse behind a few of those doors, we asked our readers to tell us about their current jobs, explain how they got them and offer their advice for anyone interested in pursuing a similar career. Here, six recent graduates share their stories

Jim Robinson

Studied: DPhil in semiconductor physics, University of Oxford, 2005

Now: senior policy adviser, UK Cabinet Office

I have always been interested in politics and current affairs, but I’ve also always loved physics. So after I obtained my MPhys from Oxford in 2002, I carried straight on with a DPhil, studying indium gallium nitride (InGaN) quantum dots for use in quantum-computing applications.

In the summer between finishing my MPhys and starting my DPhil, however, I also took part in a student-led summer programme that involved teaching English in China. This started me thinking about other possible careers, such as management. It also gave me a strong interest in Asia. I returned to the programme again in the summers of 2003 and 2004, and when an opportunity came to spend the final year of my DPhil at the University of Tokyo, I leapt at the chance to learn Japanese while also doing more research on InGaN.

Although I still enjoyed research, while I was in Japan it became clear that a career in science probably wasn’t for me. There was the limited job security to consider, and sometimes it felt like only a handful of people in the world understood what I was working on. I felt I wanted to do something that would contribute to society in a more “hands on” way.

Quite a few of my friends were interested in the civil service, which linked to my interest in politics. So I applied to the civil service’s “Fast Stream” programme – a graduate scheme that offers a series of varied one-year posts, combined with intensive training. After I was accepted, in early 2006 I was posted to the Department for Transport. I spent nearly five years there working on a variety of topics, including taking legislation to make bus travel free for the over-60s through Parliament, as well as plans for a new high-speed railway line from London to Birmingham. I also had a fascinating stint as a private secretary to the top civil servant in the department, a job that gave me an overview of everything from airports policy to vehicle safety.

Last year I moved to the Cabinet Office, the central department that works closely with the Prime Minister’s office at Number 10 and co-ordinates policy across the government. I am based in the Office for Civil Society, which is taking the lead on the government’s “Big Society” agenda. At the moment, I am working on a new way to deliver public services that involves using private investment to pay for early intervention, saving money for the public sector in the longer term. The job is fascinating. One day I might be briefing officials in Number 10, the next I could be working with local authority officers in the Midlands or talking to potential investors in the City of London.

My team’s focus on “troubled families” meant that our profile was suddenly raised by the riots in August, and an announcement on our work later in the month got quite a bit of attention in the press. After weeks of building up to an announcement, it’s always nice to see your work featured in the media, especially when linked to recent events.

Quite a few of my colleagues in the Cabinet Office are economists, but there are also a surprising number of physicists. Of course, I never use my experimental skills, but my more “generic” physics training tends to be quite useful for tasks such as understanding data, setting up spreadsheets and clearly explaining complicated concepts. Above all, I think my physics background helps me to understand how complicated systems fit together – the difference being that those systems are now in public policy. I do miss physics – and still read Physics World every month! – but I’m happy with the choice I’ve made.

Hayley Smith

Studied: MPhys in physics with astrophysics, University of York, 2009

Now: accelerator physicist, ISIS Spallation Neutron Source, UK

I did not begin to consider my career options seriously until the start of my final year at university, when many high-profile companies begin hiring. This was because, unlike many of my peers, I had no firm ideas regarding my best move into the workplace. As I was still enjoying physics, I focused my efforts on science- or engineering-based roles. Quite soon, though, I decided that graduate schemes – which enable graduates to become established within their desired industry while receiving various training and development opportunities – seemed appealing. In fact, there were initially more than 30 that interested me, and it took me a while to narrow the field down to my current employer: the ISIS Spallation Neutron Source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire.

ISIS is operated by the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council, and it consists of a linear accelerator and synchrotron that combine to accelerate protons to 800 MeV. As an accelerator physicist I apply my physics knowledge every day. The work is varied: a mix of developing computer models/tools, and “hands on” operational duties in the ISIS synchrotron main control room. Development is a key factor in STFC’s graduate scheme: there are many training opportunities to enhance non-technical skills – including the chance to sail a tall ship with fellow graduates for four days. Alongside being great fun, this also helped developed certain key competencies such as communication, teamwork and leadership skills. Travelling abroad for two accelerator physics courses, attending and displaying work at an international conference and being invited to spend a month working alongside colleagues at a similar facility in Japan have all contributed to my technical development and have been fantastic experiences.

After I complete my initial two years on the graduate scheme (which is accredited by the Institute of Physics, publishers of Physics World), I know I will continue to have opportunities at ISIS for challenging work and further personal development, including building the skills required to achieve chartered physicist (CPhys) status. People had always told me you could do a lot with physics, but I never really believed them. I do now: the variety is astounding!

My advice for current, or recent, physics graduates is to start researching early, because applications and assessment centres are time-consuming, requiring a lot of preparation. It is also good to take time to audit your skills and research all options thoroughly to find the ones that suit you best. One of the most useful exercises you can do is to identify your skills and match them to employer requirements. In my case, I gained relevant experience through the Summer Undergraduate Research Experience (SURE) programme at the University of Leicester, but I could also mention skills I had picked up in previous warehouse and clerical employment. After working on applications through the autumn term of my final year at university, I found myself in the very fortunate position of having two graduate scheme offers by Christmas. After choosing to go for STFC, I was able to concentrate fully on the remainder of my studies.

Ewan O’Sullivan

Studied: PhD in astronomy, University of Birmingham, 2002

Now: Marie Curie Fellow, University of Birmingham, UK

I really enjoyed my PhD and decided quite early on that I wanted to stay in academia when I finished. My career since then has been shaped by the fact that astrophysics is a very international field. The researchers I worked with as a PhD student at Birmingham all had international collaborators and regularly travelled to visit colleagues or use observatories in exotic locations – Hawaii, Chile, Australia. It was also clear that most UK astronomy groups expected candidates for long-term jobs to have worked overseas. I wanted to work in X-ray astronomy, which depends on satellite observatories because the atmosphere absorbs X-rays before they can reach the ground. I was lucky enough to finish my PhD just as two new satellites were being launched: NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton. I applied for posts in the US and Canada, and was offered a postdoc position at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts – one of the world’s leading centres for X-ray astronomy. Initially I expected to work there for two or three years, but I liked working at the centre and really enjoyed living in New England, so ended up staying for seven years.

A major benefit of working in the US was that I was able to apply for NASA funding for my own projects and fairly quickly found myself in a position to define my own research programme. Many postdocs are hired to work on a specific project and don’t have much time for their own interests, but having my own funding meant that I was effectively my own boss, so I was able to try working in new areas, form new collaborations and decide for myself which scientific questions I wanted to explore. Living abroad also has its benefits. Quite apart from making friends I would never otherwise have met, I think I now have a much clearer view of how society works both in the UK and abroad, and of the place of scientists within it.

The downside is a lack of stability. Long-term jobs are scarce at the moment, and there is an expectation that you will be willing to move countries to take up a new post, which can be a problem if you have a partner or family. However, for me the benefits have been enormous. Thanks to a fellowship from the EU, I moved back to the UK in 2009, but next year I plan to take extended trips back to the US and also to India to learn low-frequency radio techniques.

Owen Dias

Studied: BSc in chemical physics, University of Bristol, 2006

Now: IT co-ordinator at a small electronics manufacturer, UK

I work for Danlers, a small Wiltshire-based firm that makes energy-saving electronic controls such as passive-infrared and time-lag switches. I actually started working for the company on a part-time basis when I was 16. My first job was building point-of-sale display boards to go in wholesalers, but in subsequent summers, I volunteered to build the company website. As time went on, I was given more and more responsibility for looking after IT for the company, and when I graduated in 2006 with a degree in chemical physics, I was offered a full-time post as the IT co-ordinator. I am now solely responsible for IT in the company, which means I have a wide variety of responsibilities, including setting up servers, technical support, staff training, IT purchasing and anything else you would file under IT.

While there aren’t any obvious parallels between chemical physics and my work in IT, the thought process involved in problem-solving – not to mention the technical abilities needed to get various machines and simulations to work in experimental and theoretical environments – were all developed during my degree, and they have helped me immensely. Having a scientific degree has also opened doors for me to work on non-IT projects within the company’s engineering department. This initially meant doing some lab work, including heat tests, electrical tests and tests aimed at finding product limitations – sometimes by blowing them up! Obviously, experimental technique and report writing plays a huge role in this. More recently, I have been project-managing the redesign of some of our products to take advantage of surface-mount technology, which allows us to use smaller mechanically placed components, which in turn means that we can make more compact and cost-efficient designs.

If any graduates are looking at small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) for future employment, I would definitely recommend just getting a foot in the door, because opportunities are dependent on your skills and not on which department you are currently in. I really enjoy working in an SME environment because of the flexibility and variety of work that is available – I don’t know any big business that would let people from their IT department blow stuff up in a lab!

Katherine Inskip

Studied: PhD in astrophysics, University of Cambridge, 2002

Now: postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Germany

When I was younger, I always knew I wanted to work abroad, and that I wanted to be both an astronomer and a mother. Today, I am doing all of those things…well, almost.

I am currently in the middle of my third post as a postdoctoral researcher, a mother to two young sons and living in Germany. Right now, I am on maternity leave for my second son. But for someone taking a career break, I am still surprisingly busy. I may have replaced the challenges of interpreting awkward data and assisting students with the challenges of interpreting an awkward baby and potty-training a toddler, but there is still science in my day-to-day life as well. There are papers to read (and write) and telescope observations to prepare for, although thankfully the observations will be done by observatory staff in “service mode”, so I do not have to go to the Very Large Telescope in Chile myself. Weather permitting, the data should be delivered to me just in time for me to return to work. And there’s always more work to be done, if you can find the time for it – but if I tried that, I think I would go crazy.

Combining a career with motherhood inevitably means making some sacrifices, especially when you have to put the needs of two small boys first. Conferences have become a particular difficulty. The networking and learning opportunities they present are marvellous, but without suitable childcare facilities, most of them are impossible for me right now. Even so, while I may not be keeping up with the literature as well as I would like, and my own research is temporarily on hold, thanks to the support of my colleagues, I hope I will not be too out of touch when I return to part-time work next year.

So what advice could I offer to my former student self on how to get where she wants to be in life? To be honest, I think she would have a thing or two to say to me instead – “What took you so long?” would probably sum it up. The best answer I can give is: don’t be afraid to take risks. There is never a “good” time to start a family – if you want one, go for it. And don’t stay in your comfort zone career-wise, either. Move institutes, move countries if possible – there’s so much experience to be gained, in so many aspects of life. It’s not an easy balancing act, to be sure, but it keeps me happy.

Chris King

Studied: PhD in semiconductor physics, University of Nottingham, 2008

Now: technical adviser at Sellafield Ltd, UK

I completed my PhD in December 2008 and started on the Sellafield Ltd graduate scheme in October 2009. Sellafield’s primary focus is the safe decommissioning of nuclear “legacy ponds and silos” – facilities that in some cases date back several decades and that contain an assortment of historical material. Understanding the physical contents of these facilities and their chemistry, plus figuring out how to safely remove and process that material, are enormous technical challenges. Sellafield is also involved in the reprocessing of spent civil nuclear fuel, to separate out the uranium, plutonium and radioactive waste products.

I chose to enter via the graduate scheme for a number of reasons, including the fact that the months between the end of my PhD and the start of the scheme gave me an opportunity to travel. However, the main reason was that I had decided to move from academia into industry, and I saw a graduate scheme as the best way to experience a range of roles to help set the foundation for my subsequent career path. I was pleasantly surprised to find that several other PhD-holders had made the same decision.

As a technical adviser, my role is to provide general technical and scientific knowhow on a variety of projects across the Sellafield site. Projects I have been involved in to date include: designing on-plant trials to investigate ways of improving performance; modelling material flows through the plant; reviewing laboratory analysis strategies; ensuring the calibration of equipment; doing calculations; and analysing raw data. My job also has less-technical aspects such as producing management procedures that ensure that Sellafield complies with its own policies, regulator requirements and customer specifications. I use specific physics from time to time, but it is the wider technical skills and knowledge I learned at university – both as an undergraduate and during my PhD – that are key to my job.

Although I am back in a technical role now, participating in the graduate scheme meant that I spent 12 months on a secondment to the nuclear safeguards department, where I managed a site-wide programme with the main function of providing feedback to national and international regulators. This is an opportunity that would have been difficult to come by as a direct entrant, and I feel that this experience of “stakeholder relations” will be of huge use in my future career.

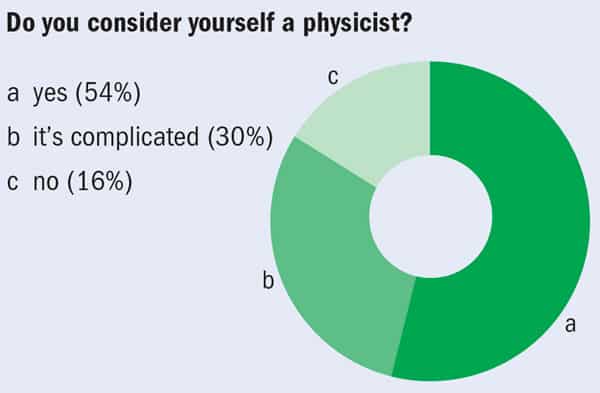

But are you a physicist?

Do you need to have a job in physics to consider yourself a physicist, or is being a physicist more about training and habits of thought? With more than half of those who responded to the Institute of Physics’ 2007 survey picking something other than research to describe the main function of their jobs, it seemed to be a relevant question – so we asked it. Below are some of the responses we received to a poll conducted on Facebook.

Yes

I joined a physics course despite everyone advising me to go for engineering; so yes, I’m obviously a physicist.

– Srikanth Suresh

I like to consider myself a physicist as I have the relevant training, read about it and think like it, but I fear since I haven’t been in the lab for three years, my “physicistique” may have expired.

– Kate Oliver

It’s complicated

If I were a quantum-mechanics guy, the best answers I could give you would be both “yes” and “no”.

– Dan Lipford

I feel I can’t call myself a physicist because I don’t have anything hanging on the wall saying “Tom Sullivan is hereby a physicist”.

– Tom Sullivan

Do I consider myself a physicist? Mmmm, well I’m pretty good at woodwork but I don’t consider myself a carpenter, I’m pretty good with pipes and electricity but I wouldn’t say I was a plumber or an electrician. I think to be a physicist you’ve got to specialize in it, rather than just be pretty good at it.

– Steve Douglas

No

I guess if you consider that everything we do is affected by physical laws and principles, then my answer would be yes, we’re all physicists on that level. But ultimately I am not a physicist by trade, I am a law student. Shout out for the law of conservation of energy and for Bernoulli’s principle, as they are my favourites!

– Amy Wheeler-Smith

I’m an archaeologist, a frustrated scientist in a sometimes deeply unscientific discipline. Physics is a hobby, and what a wonderful one it is.

– Rich McGregor Edwards

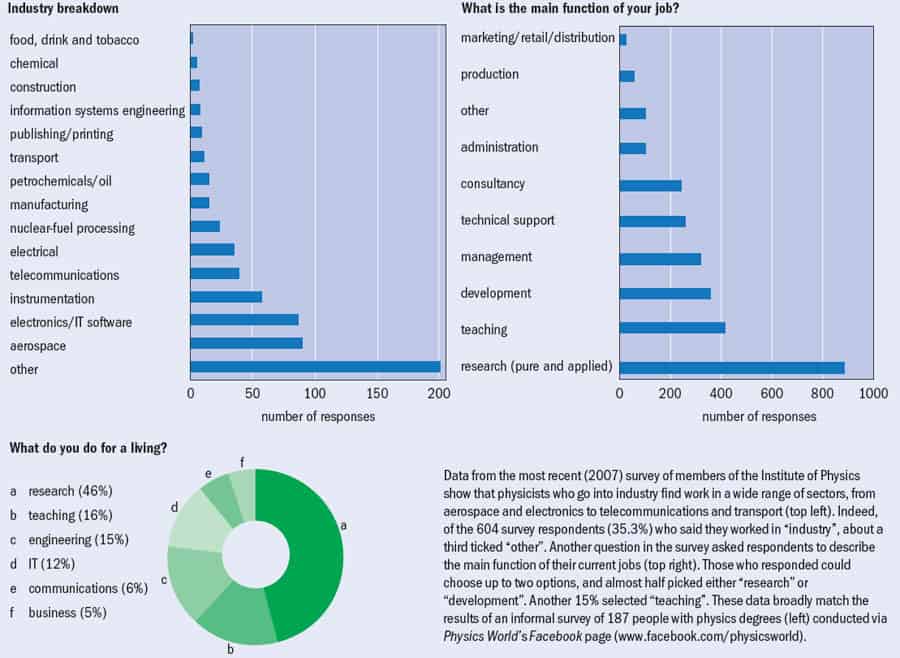

What physicists do: survey results

Data from the most recent (2007) survey of members of the Institute of Physics show that physicists who go into industry find work in a wide range of sectors, from aerospace and electronics to telecommunications and transport (top left). Indeed, of the 604 survey respondents (35.3%) who said they worked in “industry”, about a third ticked “other”. Another question in the survey asked respondents to describe the main function of their current jobs (top right). Those who responded could choose up to two options, and almost half picked either “research” or “development”. Another 15% selected “teaching”. These data broadly match the results of an informal survey of 187 people with physics degrees (left) conducted via Physics World‘s Facebook page (www.facebook.com/physicsworld).