Magnets generally have two poles, north and south, so observing something that behaves like it has only one is extremely unusual. Physicists in Germany and Switzerland have become the latest to claim this rare accolade by making the first direct detection of structures known as orbital angular momentum monopoles. The monopoles, which the team identified in materials known as chiral crystals, had previously only been predicted in theory. The discovery could aid the development of more energy-efficient memory devices.

Traditional electronic devices use the charge of electrons to transfer energy and information. This transfer process is energy-intensive, however, so scientists are looking for alternatives. One possibility is spintronics, which uses the electron’s spin rather than its charge, but more recently another alternative has emerged that could be even more promising. Known as orbitronics, it exploits the orbital angular momentum (OAM) of electrons as they revolve around an atomic nucleus. By manipulating this OAM, it is in principle possible to generate large magnetizations with very small electric currents – a property that could be used to make energy-efficient memory devices.

Chiral topological semi-metals with “built-in” OAM textures

The problem is that materials that support such orbital magnetizations are hard to come by. However, Niels Schröter, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle, Germany who co-led the new research, explains that theoretical work carried out in the 1980s suggested that certain crystalline materials with a chiral structure could generate an orbital magnetization that is isotropic, or uniform in all directions. “This means that the materials’ magnetoelectric response is also isotropic – it depends solely on the direction of the injected current and not on the crystals’ orientation,” Schröter says. “This property could be useful for device applications since it allows for a uniform performance regardless of how the crystal grains are oriented in a material.”

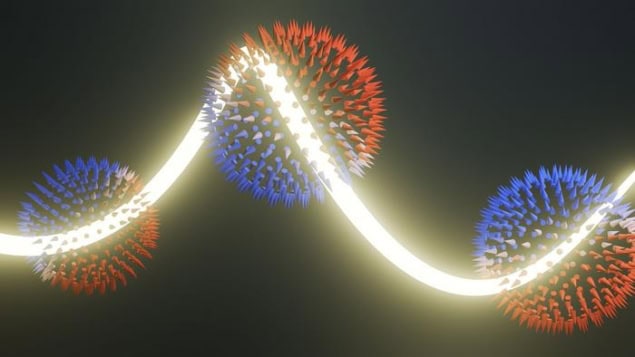

In 2019, three experimental groups (including the one involved in the latest work) independently discovered a type of material called a chiral topological semimetal that seemed to fit the bill. Atoms in these semimetals are arranged in a helical pattern, which produces something that behaves like a solenoid on the nanoscale, creating a magnetic field whenever an electric current passes through it.

The advantage of these materials, Schröter explains, is that they have “built-in” OAM textures. What is more, he says the specific texture discovered in the most recent work – an OAM monopole – is “special because the magnetic field response can be very large – and isotropic, too”.

Visualizing monopoles

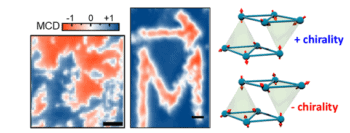

Schröter and colleagues studied chiral topological semimetals made from either palladium and gallium or platinum and gallium (PdGa or PtGa). To understand the structure of these semimetals, they directed circularly polarized X-rays from the Swiss Light Source (SLS) onto samples of PdGa and PtGa prepared by Claudia Felser’s group at the Max Planck Institute in Dresden. In this technique, known as circular dichroism in angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (CD-ARPES), the synchrotron light ejects electrons from the sample, and the angles and energies of these electrons provide information about the material’s electronic structure.

“This technique essentially allows us to ‘visualize’ the orbital texture, almost like capturing an image of the OAM monopoles,” Schröter explains. “Instead of looking at the reflected light, however, we observe the emission pattern of electrons.” The new monopoles, he notes, reside in momentum (or reciprocal) space, which is the Fourier transform of our everyday three-dimensional space.

Complex data

One of the researchers’ main challenges was figuring out how to interpret the CD-ARPES data. This turned out to be anything but straightforward. Working closely with Michael Schüler’s theoretical modelling group at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland, they managed to identify the OAM textures hidden within the complexity of the measurement figures.

Contrary to what was previously thought, they found that the CD-ARPES signal was not directly proportional to the OAMs. Instead, it rotated around the monopoles as the energy of the photons in the synchrotron light source was varied. This observation, they say, proves that monopoles are indeed present.

Researchers find ‘lost’ angular momentum

The findings, which are detailed in Nature Physics, could have important implications for future magnetic memory devices. “Being able to switch small magnetic domains with currents passed through such chiral crystals opens the door to creating more energy-efficient data storage technologies, and possibly also logic devices,” Schröter says. “This study will likely inspire further research into how these materials can be used in practical applications, especially in the field of low-power computing.”

The researchers’ next task is to design and build prototype devices that exploit the unique properties of chiral topological semimetals. “Finding these monopoles has been a focus for us ever since I started my independent research group at the Max Planck Institute for Microstructure Physics in 2021,” Schröter tells Physics World. The team’s new goal, he adds, is to “demonstrate functionalities and create devices that can drive advancements in information technologies”.

To achieve this, he and his colleagues are collaborating with partners at the universities of Regensburg and Berlin. They aim to establish a new centre for chiral electronics that will, he says, “serve as a hub for exploring the transformative potential of chiral materials in developing next-generation technologies”.