The 2020 Nobel Prize for Physics will be announced on Tuesday 6 October. In the run-up to the announcement, Physics World editors have picked some of the people who they think have been overlooked for a prize in the past

The discovery of nuclear fission in 1938 is among the most momentous events in 20th-century physics. Within seven years, this experimental and theoretical breakthrough – made jointly by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, who obtained the data, and by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, who interpreted it – led to the first atomic weapons. Less than a decade later, it led to the first nuclear power plants. If ever there was a discovery that should have won its instigators a Nobel Prize in Physics, nuclear fission is surely it.

But that’s not what happened. Though the terms of Alfred Nobel’s bequest would have allowed three of Hahn, Frisch, Meitner and Strassmann to share a prize, only Hahn got the nod, becoming the sole recipient of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei”. The contributions of Frisch, Meitner and Strassmann were relegated to a few lines in the official Nobel presentation speech, which took place in December 1945. That same speech, incidentally, claims that Hahn “never dreamed of giving Man control over atomic energy” – which is a bit rich, given that Hahn worked on the Nazi atomic weapons programme and was in fact still incarcerated by the British authorities at the time.

The 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry represents a strong challenge to anyone who claims that the Nobels are fair or reflective of how collaborative science works. Strassmann, whom the presentation speech patronizingly called “one of [Hahn’s] young colleagues”, had in fact been his assistant for the best part of a decade. For much of that period, Strassmann worked for half wages or none; his opposition to the Nazi regime meant that he was blacklisted from other jobs, leaving him dependent on Hahn and unable to develop a solo career. Meitner fared slightly better in the speech, since it did at least acknowledge her as Hahn’s collaborator for more than 30 years. Not mentioned, though, is the reason she was absent during the crucial 1938 experiments: Meitner, like her nephew Frisch, was an ethnic Jew, and her conversion to Protestantism 30 years earlier did not protect her from Nazi predation. In the summer of 1938, both Meitner and Frisch were forced to flee Germany. They made their seminal contributions to fission in exile, communicating with the Berlin-based Hahn and Strassmann by letter and telephone.

Of the three researchers left out of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, the injustice done to Meitner is the most severe. Unlike the other “overlooked” physicists in this series, the records of her Nobel nominations are now public. They show that Meitner’s male colleagues (the scientists in the Nobel nomination pools were all male then, notwithstanding the existence of contemporary female luminaries like Ida Noddack and Iréne Joliot-Curie) nominated her for the physics Nobel 29 times, and for the chemistry Nobel 19 times. Her earliest nomination came from the Norwegian chemist Heinrich Goldschmidt in 1924. Her last was in 1965, three years before her death, when Max Born made her his fourth choice after Pyotr Kapitsa (who went on to win in 1978), Cornelis Gorter (who never won) and Walter Heitler (ditto).

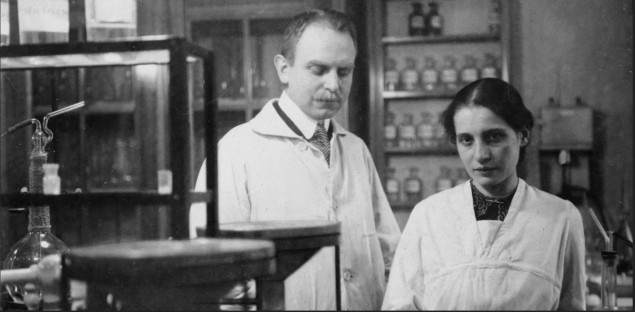

Profiles of genius and persecution

The records do not entirely explain why none of these nominations were successful. However, they do suggest that Meitner has something other than gender in common with two other entries in this series. The chemistry Nobel committee in 1944 was as divided about the relative importance of theory and experiment as the physics committee was in 1957, when Chien-Shiung Wu was denied a share of the parity-violation prize that went to Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee. The 1944 committee also failed to appreciate the major role that Meitner, Frisch and Strassmann played in the fission collaboration, much as a later committee failed to understand that Jocelyn Bell Burnell was not merely Antony Hewish’s assistant in discovering pulsars. On top of that, a whole suite of prejudices – racial, sexual, political and disciplinary – seems to have made it impossible for the parochial chemists of neutral Sweden to see the contributions of a refugee Jewish woman physicist in their proper light.

Early in her career, Meitner faced and overcame a considerable degree of personal prejudice. In one laughable example, the Nobel laureate Emil Fischer refused to let her work in his lab because he thought women’s long hair was a fire hazard (apparently Fischer’s massive beard was perfectly fine). Meitner’s subsequent achievements – as well as nuclear fission, she also discovered the element protactinium – won her legions of admirers, 26 of whom went on to nominate her for a Nobel Prize at least once. In the end, though, neither her efforts nor theirs were enough to counterbalance the subtle, structural forces that helped (and still do help) to keep the Nobel prizes overwhelmingly white and male, 82 years after Lise Meitner’s earth-shattering discovery.