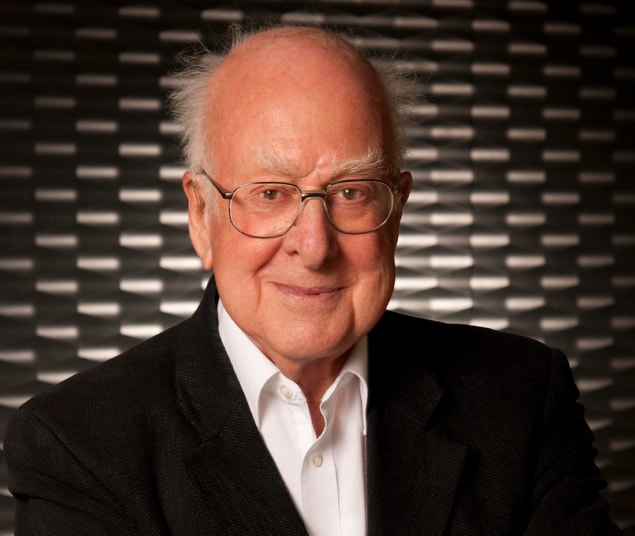

The British theoretical physicist Peter Higgs, whose work led to the discovery of the Higgs boson, died yesterday on 8 April at the age of 94. Higgs’s work, which he carried out in the early 1960s, resulted in the prediction of a new particle, setting in motion a decades-long hunt for it. The Higgs boson was finally discovered at the CERN particle-physics lab near Geneva in 2012, with Higgs going on to share half of the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics together with the Belgium physicist François Englert.

Born on 29 May 1929 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in north-east England, Higgs attended Cotham Grammar School in Bristol, UK, where his father was stationed as an engineer for the BBC during the Second World War. He later enrolled as a physics undergraduate at King’s College London, where he also did a PhD on the theory of molecules. Higgs then worked at several British universities before settling at the University of Edinburgh in 1960, where he remained until retirement in 1996.

It was at Edinburgh where Higgs did his ground-breaking research. In 1964 he and Englert published papers independently of each other about a mechanism that could give rise to the origin of mass of subatomic particles. It arises from a symmetry-breaking event that occurred in the very early universe that created a uniform scalar field known as the Higgs field that pervades all space. Elementary particles such as leptons, quarks and the W and Z bosons conveying the weak force “acquire” their distinctive masses by virtue of their unique and different couplings to this field. Englert and Higgs bag Nobel Prize for Physics

Wave–particle duality, which lies at the heart of quantum mechanics, dictates that vibrations in this field should give rise to a spin-0 particle known as the Higgs boson. Just as vibrating the electromagnetic field generates waves corresponding to photons, so should shaking the Higgs field create such bosons. The work by Higgs and others triggered a long quest to discover the particle using huge particle colliders.

But the tricky aspect that faced particle physicists is that the energy required to create detectable quantities of Higgs bosons was unknown. The answer, however, came in 2012 at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which had first switched on just four years earlier. Physicists working on the LHC’s giant ATLAS and CMS detectors analysed vast numbers of proton–proton collisions at 8 TeV and found strong evidence for the Higgs boson with a mass of about 125 GeV.

Without his theory, atoms could not exist and radioactivity would be a force as strong as electricity and magnetism

John Ellis

A year following CERN’s discovery, Higgs shared half of the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics with Englert. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded it to the pair “for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles, and which recently was confirmed through the discovery of the predicted fundamental particle, by the ATLAS and CMS experiments”.

As well as the Nobel prize, Higgs won many other awards including the Paul Dirac Medal and Prize from the Institute of Physics in 1997, the Wolf Prize in Physics (2004) and the American Physical Society J J Sakurai Prize (2010).

In 1999 Higgs turned down a knighthood, but in 2012 he accepted membership of the Order of the Companions of Honour. The following year he was granted the Freedom of the City of Bristol and in 2014 he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Newcastle and the Freedom of the City of Edinburgh.

Modest and remarkable

Tributes to Higgs have flowed in from the world of physics. “Besides his outstanding contributions to particle physics, Peter was a very special person, an immensely inspiring figure for physicists across the world, a man of rare modesty, a great teacher and someone who explained physics in a very simple and yet profound way,” said CERN director general Fabiola Gianotti. “An important piece of CERN’s history and accomplishments is linked to him. I am very saddened, and I will miss him sorely.”

Particle physicist John Ellis from King’s College London, who has spent most of his career at CERN, told Physics World that “a giant of particle physics has left us”. Tracks of my tears: the true meaning of Peter Higgs’ emotion at CERN in 2012

“Without his theory, atoms could not exist and radioactivity would be a force as strong as electricity and magnetism,” adds Ellis. “His prediction of the existence of the particle that bears his name was a deep insight, and its discovery at CERN in 2012 was a crowning moment that confirmed his understanding of the way the universe works.”

Keith Burnett, president of the Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics World, notes that Higgs was a “true giant of physics”.

“Higgs’s legacy as the proposer of the Higgs boson and as the joint winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics made him one of the most significant figures in world science,” notes Burnett. “His life’s work is certain to continue to inspire, inform and advance our understanding of the universe for many generations to come.”

Peter Mathieson, principal and vice chancellor at Edinburgh, said Peter Higgs was a “remarkable individual”. He was “a truly gifted scientist whose vision and imagination have enriched our knowledge of the world that surrounds us [whose] pioneering work has motivated thousands of scientists, and his legacy will continue to inspire many more for generations to come.

Shunning the limelight

In an interview with Physics World in 2012 shortly before the discovery of the Higgs boson was announced, Higgs expressed his embarrassment at having a particle named after him. Always self-effacing, he felt it placed too much credit on him at the expense of other theorists, constantly referring during the interview instead to the “so-called Higgs boson”. Higgs also admitted that he did not want to write an autobiography as he was “too lazy”. Peter Higgs: the man behind the machine

Particle physicist Frank Close, who wrote a biography of Peter Higgs in 2022 called Elusive: How Peter Higgs Solved the Mystery of Mass, told Physics World how Higgs disliked the limelight and that his style was to work in isolation. Yet Close adds that Higgs was “comfortable in the company of friends and colleagues, and always a delight to talk with”.

“We shared the [COVID-19] lockdown in 2020 by talking on the phone every Friday or Saturday for one or two hours, from which I gradually put together the story of how his life changed when the boson became headline news following its description as The God Particle – a moniker that Peter, an atheist, disliked,” notes Close. “I was astonished when he admitted to me ‘It ruined my life’ – a quote that I double checked with him before including it [in the book].”