A network of optical cavities could be used to detect gravitational waves (GWs) in an unexplored range of frequencies, according to researchers in the UK. Using technology already within reach, the team believes that astronomers could soon be searching for ripples in space–time across the milli-Hz frequency band at 10⁻⁵ Hz–1 Hz.

GWs were first observed a decade ago and since then the LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA detectors have spotted GWs from hundreds of merging black holes and neutron stars. These detectors work in the 10 Hz–30 kHz range. Researchers have also had some success at observing a GW background at nanohertz frequencies using pulsar timing arrays.

However, GWs have yet to be detected in the milli-Hz band, which should include signals from binary systems of white dwarfs, neutron stars, and stellar-mass black holes. Many of these signals would emanate from the Milky Way.

Several projects are now in the works to explore these frequencies, including the space-based interferometers LISA, Taiji, and TianQin; as well as satellite-borne networks of ultra-precise optical clocks. However, these projects are still some years away.

Multidisciplinary effort

Joining these efforts was a collaboration called QSNET, which was within the UK’s Quantum Technology for Fundamental Physics (QTFP) programme. “The QSNET project was a network of clocks for measuring the stability of fundamental constants,” explains Giovanni Barontini at the University of Birmingham. “This programme brought together physics communities that normally don’t interact, such as quantum physicists, technologists, high energy physicists, and astrophysicists.”

QTFP ended this year, but not before Barontini and colleagues had made important strides in demonstrating how milli-Hz GWs could be detected using optical cavities.

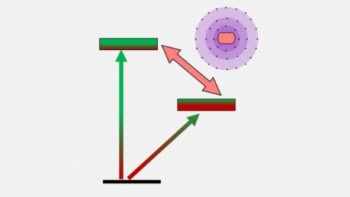

Inside an ultrastable optical cavity, light at specific resonant frequencies bounces constantly between a pair of opposing mirrors. When this resonant light is produced by a specific atomic transition, the frequency of the light in the cavity is very precise and can act as the ticking of an extremely stable clock.

“Ultrastable cavities are a main component of modern optical atomic clocks,” Barontini explains. “We demonstrated that they have reached sufficient sensitivities to be used as ‘mini-LIGOs’ and detect gravitational waves.”

When such GW passes through an optical cavity, the spacing between its mirrors does not change in any detectable way. However, QSNET results have led to Barontini’s team to conclude that milli-Hz GWs alter the phase of the light inside the cavity. What is more, they conclude that this effect would be detectable in the most precise optical cavities currently available.

“Methods from precision measurement with cold atoms can be transferred to gravitational-wave detection,” explains team member Vera Guarrera. “By combining these toolsets, compact optical resonators emerge as credible probes in the milli-Hz band, complementing existing approaches.”

Ground-based network

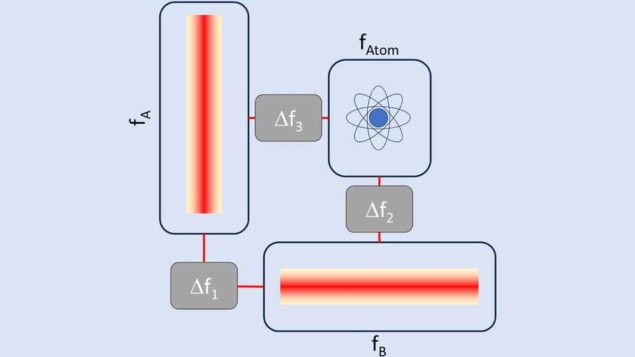

Their compact detector would comprise two optical cavities at 90° to each other – each operating at a different frequency – and an atomic reference at a third frequency. The phase shift caused by a passing gravitational wave is revealed in a change in how the three frequencies interfere with each other. The team proposes linking multiple detectors to create a global, ground-based network. This, they say, could detect a GW and also locate the position of its source in the sky.

By harnessing this existing technology, the researchers now hope that future studies could open up a new era of discovery of GWs in the milli-Hz range, far sooner than many projects currently in development.

“This detector will allow us to test astrophysical models of binary systems in our galaxy, explore the mergers of massive black holes, and even search for stochastic backgrounds from the early universe,” says team member Xavier Calmet at the University of Sussex. “With this method, we have the tools to start probing these signals from the ground, opening the path for future space missions.”

Barontini adds, “Hopefully this work will inspire the build-up of a global network of sensors that will scan the skies in a new frequency window that promises to be rich of sources – including many from our own galaxy,”.

The research is described in Classical and Quantum Gravity.