Last weekend, over 70,000 visitors travelled to Geneva for the CERN Open Days – a rare chance to visit the world’s largest particle physics facility while its accelerators are switched off for the “long shutdown”. I was one of the lucky thousands who got to have a look around the sites.

The scale of the event was massive – CERN shut down roads and laid on an entire bus network to transport people to nine sites in and around the 27 km accelerator ring. The LHC’s big four underground experiments – ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb – were major crowd-pullers. Visitors flocked to join long queues to don hard-hats, pile into packed lifts, and travel deep underground into the detector caverns.

The 14 000-tonne CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) detector, one of the two experiments that discovered the Higgs boson, was particularly impressive. The detector, which is 21 m long, 15 m wide and 15 m high, currently has its various sectors pulled apart for the scientists to access. This separation granted visitors a full-on, close-up experience of the enormous, complex – and rather photogenic – detector structures.

And there was plenty to see above ground too, including numerous hands-on exhibits such as a superconducting levitating scooter shuttling small children back and forth, and the Super Plastic Synchrotron, a fully featured toy particle accelerator. The table-top Super Plastic Synchrotron challenged visitors to inject, accelerate and keep a small steel ball circulating around a plastic ring. The ultimate aim: “to reach the incredible 0.000,001% of the speed of light”.

CERN’s Martin Söderén and Daniel Valúch built the Super Plastic Synchrotron to echo the structure of the LHC, with eight sectors containing straight and curved portions. The “particles”, ferromagnetic steel balls, are pre-accelerated by gravity (dropping from a height of 22 cm) and then injected into the plastic tubing.

It’s then up to the users to accelerate the ball further by controlling two electromagnets placed around the ring. The accelerator – which took about four weeks to design and build – also includes ball position monitors based on photo-elements, an extraction system and a beam dump.

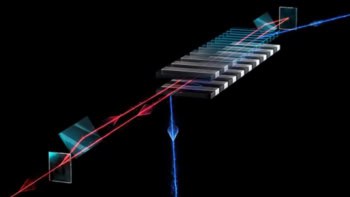

Another facility that caught my eye was the fantastically named Antimatter Factory. Here, two deceleration rings – the Antiproton Decelerator and ELENA – slow down antiprotons (created by firing protons from the Proton Synchrotron into a block of metal) to speeds at which they can be confined and studied. CERN researchers then use these particles to perform a range of experiments comparing the properties of matter and antimatter.

We received a guided tour of both decelerators (and another foray underground) from an enthusiastic and engaging CERN researcher working on the GBAR (Gravitational Behaviour of Antihydrogen at Rest) experiment. This particularly intriguing study hopes to discover whether antimatter, in the form of antihydrogen atoms, falls up or down under the influence of gravity.

Once the shutdown is over and CERN fires up all its machines once more, hopefully I’ll get to find out.