When Physics World learned that an Australian astrophysicist had tried to invent a device to keep people from touching their faces during the coronavirus pandemic, only to wind up in hospital with four neodymium magnets stuck up his nose, our first thought was, “Is it April Fool’s Day in Australia already?”

Our second thought, though, was, “Yeah, that sounds like something a physicist would do.”

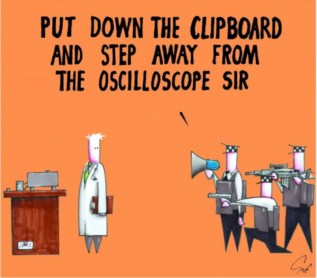

We write a lot about physicists. We’re regularly amazed and humbled by the creativity and cleverness they show in the face of daunting scientific challenges. But we also know that physicists have a rare talent for making absolute arses of themselves – and we have a giant red folder full of stories to prove it.

So this year, in lieu of an April Fool (and to reassure the above-mentioned Aussie, Daniel Reardon, that getting magnets stuck up your nose during a pandemic is not, in fact, the dumbest thing a physicist has ever done – although it’s close), we present five additional astonishing displays of idiocy by otherwise highly intelligent people. All are drawn from the Physics World archives and compiled by our emergency otolaryngology correspondent Ken Heartley-Wright, who is currently self-isolating at his country home in Borsetshire. Enjoy!

That’s not (n)ice

Like Reardon, Muhammad “Moe” Qureshi made a fool of himself while attempting to aid the battle against a terrible illness. In the “ice bucket challenge” of 2014, celebrities, politicians and ordinary folk lined up to pour buckets of ice over their heads to raise money for research on motor neurone disease. The late physicist Stephen Hawking, who lived with the condition for more than 50 years, was among the participants.

But Qureshi, who was then a nanotechnologist at the University of Toronto in Canada, decided to go one better than Hawking et al. “Instead of using ice water, we’re going to be using liquid nitrogen,” he announced to the camera as a collaborator filmed his don’t-try-this-at-home stunt. “This is extremely dangerous and not safe, but we’re going to do it anyway.” A few seconds later, the video shows Qureshi pouring a substantial quantity of steaming liquid nitrogen over his head.

Unlike Reardon, Qureshi did not require hospital treatment. However, the footage of him dancing around yelling “Oh my gosh, that’s cold!” while frantically trying to remove the 77 K liquid from his hair, T-shirt and shorts should nevertheless give would-be imitators pause.

Stranded tardigrades

Scientists have long wondered whether life exists outside the Earth. In April 2019, an Israeli space mission may have answered that question by accidentally populating the Moon with tardigrades. These creatures, also known as water bears, can survive in some of Earth’s most extreme environments, and they were flown to the Moon aboard the Beresheet spacecraft. During the landing process, however, a malfunction caused the craft’s engines to shut down, and it crashed to the lunar surface.

Beresheet’s crew of 10,000 tardigrades were shipped to the Moon in a dehydrated state, with a dramatically reduced metabolism. Tardigrades are, however, known to endure incredibly harsh conditions – including the vacuum of space. If they survived the crash, a little water might be enough to resurrect them. It’s a long shot, of course: tardigrades have poor tolerance to solar UV radiation, and the Moon (like some supermarkets during the current pandemic) has a distinct shortage of liquid water or food. But now we’ll always be wondering.

Legal troubles, part 1

In medieval and ancient times, alchemists sought to turn base metal into gold. In the late 2000s, Iain Fielden, a physicist at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK, managed to do the opposite by turning a £60 speeding ticket into court costs exceeding £20,000.

The affair began in mid-2006, when a speed camera clocked Fielden’s wife Vikki driving around a curved street in Huddersfield at 36 mph in a 30 mph zone. Fielden, who was sitting in the passenger seat at the time, insisted she was driving at 31±3 mph. He chose to fight the ticket because, he claimed, the speed camera was situated on a curve and would only work correctly for vehicles travelling in a straight line.

So far, so reasonable. But Fielden’s efforts quickly took on the character of a crusade. After a magistrate’s court handed down the £60 fine in 2007, he, his wife and two witnesses set out in the dead of night to measure the curvature of the road using a tape measure, rope and a laser. The results showed that the radius of the road was about 600 m – half the minimum value permitted in the camera manufacturer’s guidelines.

Fielden duly challenged the magistrate court’s ruling on the basis that the police were not using the radar in line with the guidelines. But despite spending 1000 hours researching the case (and, at one point, impersonating a lawyer for the Crown Prosecution Service during a phone conversation with a witness) he lost his appeal at Bradford Crown Court – one reason being that the limit of 1200 m for the curvature was, it seems, arbitrary.

By this time, Fielden’s legal costs had reached £15,000 – an amount he said would lead to “bankruptcy, probably”. But he didn’t stop there. Instead, he pursued the matter to the High Court, where, in mid-2009, one of the judges described the suit as “doomed to fail”, dismissed it and denied Fielden a further chance to appeal. This result cost him a further £5000 in legal fees. At that point, Fielden vowed to take his case to the European Court of Human Rights. While Physics World can find no record of his having done so, the protracted battle doesn’t seem to have diminished his interest in the law: he is now part of an expert witness programme at Sheffield Hallam’s Materials and Engineering Research Institute.

Legal troubles, part 2

Fielden’s problems with the law pale in comparison with those of Paul Frampton. A British-born theorist, Frampton made a name for himself within the field of particle physics. By 2012 he was a respected but decidedly un-famous professor at the University of North Carolina in the US.

All that changed when, at the age of 71, Frampton travelled to Bolivia in hopes of meeting the Czech-born lingerie model Denise Milani, with whom he had supposedly been corresponding over the Internet. When he arrived, Milani was nowhere to be seen, but someone did turn up with a request that he carry “her” suitcase to Buenos Aires, Argentina. This he duly did – only for airport officials to find 2 kg of cocaine tucked into its lining.

Exactly how much Frampton knew about this is a vexed question. While he has always maintained his innocence, text messages sent from him to “Milani” (in reality, a fraudster whose identity remains unknown) suggest that he may have been less naïve than he claims. According to a 2013 New York Times article, the texts included comments such as “This stuff is worth nothing in Bolivia, but millions in Europe” and “Monday arrival changed. You must not tell the coca-goons.”

At his trial, Frampton claimed the messages were “jokes”; later, he hired a forensic linguist to try to prove he hadn’t written them. Neither strategy did him much good. He was sentenced to 56 months in a Buenos Aires jail, and his former employer refused to reinstate him. Still, his experiences may yet have a silver lining of sorts. In 2013, Fox Searchlight asked officials from the US film-production company Film Rites to make a film based on his life. We can only assume that the pandemic must have held up production.

Acid attack

And finally, in our roll-call of dumbest things ever in physics, Physics World is delighted to bring you this cautionary tale of Irish physicist Kevin McGuigan during his time as a PhD student.

Seeking to dope some silicon ingots with copper, McGuigan decided to melt a glass tube containing his ingredients by heating them in a furnace at 1000 °C using an “oxygen-hydrogen welding station” in the corner of his lab. Upon opening the main valves to the gas cylinders, McGuigan noticed an ominous hissing noise that he wanted to “sort out” with a “small twist” of his spanner.

Aware that hydrogen is dangerously flammable, McGuigan “panicked” and began turning the fittings on the cylinder “the wrong way”. The regulator refused to budge, prompting McGuigan to increase his “purchase” on the bottle, by wrapping his legs around the base “in an attempt to stop it spinning”.

Then, just as McGuigan was having visions of a Hindenburg-style disaster, his supervisor walked in. Upon seeing him wrapped around the hydrogen cylinder “wrestling with the regulator like a demented, pole-dancing plumber”, his boss calmly closed the cylinder’s main valve.

A nightmare was averted, but McGuigan’s day was about to take a turn for the worse.

After doping his samples, McGuigan placed them in a beaker of concentrated hydrochloric acid. While attempting to dissolve “the final traces of copper from the ingots”, he held the beaker up to the light “as you would with a fine wine”. Finally, he tried to inspect the samples’ surfaces by giving the beaker, as you do, “a good slosh”.

As luck would have it, the acid sloshed right out of the beaker and onto his groin. McGuigan jumped up, unbuckled his belt and trousers, and thrust them down by his ankles. Noticing the acid making its way onto his boxer shorts, he yanked them down too before “speed-shuffling over to a metal sink” and vigorously dousing his nether regions in water.

It was then that McGuigan’s supervisor, the head of department and a visiting female professor walked in – on an impromptu tour of the lab.

Although McGuigan was unscathed “apart from what looked like a pubic perm gone wrong”, his supervisor and the department head agreed that henceforth, McGuigan’s “theoretical and modelling skills should be enthusiastically encouraged”.