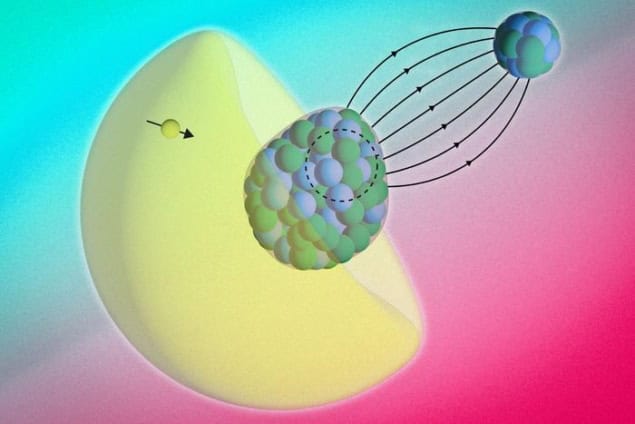

Physicists have obtained the first detailed picture of the internal structure of radium monofluoride (RaF) thanks to the molecule’s own electrons, which penetrated the nucleus of the molecule and interacted with its protons and neutrons. This behaviour is known as the Bohr-Weisskopf effect, and study co-leader Shane Wilkins says that this marks the first time it has been observed in a molecule. The measurements themselves, he adds, are an important step towards testing for nuclear symmetry violation, which might explain why our universe contains much more matter than antimatter.

RaF contains the radioactive isotope 225Ra, which is not easy to make, let alone measure. Producing it requires a large accelerator facility at high temperature and high velocity, and it is only available in tiny quantities (less than a nanogram in total) for short periods (it has a nuclear half-life of around 15 days).

“This imposes significant challenges compared to the study of stable molecules, as we need extremely selective and sensitive techniques in order to elucidate the structure of molecules containing 225Ra,” says Wilkins, who performed the measurements as a member of Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz’s research group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US.

The team chose RaF despite these difficulties because theory predicts that it is particularly sensitive to small nuclear effects that break the symmetries of nature. “This is because, unlike most atomic nuclei, the radium atom’s nucleus is octupole deformed, which basically means it has a pear shape,” explains the study’s other co-leader, Silviu-Marian Udrescu.

Electrons inside the nucleus

In their study, which is detailed in Science, the MIT team and colleagues at CERN, the University of Manchester, UK and KU Leuven in the Netherlands focused on RaF’s hyperfine structure. This structure arises from interactions between nuclear and electron spins, and studying it can reveal valuable clues about the nucleus. For example, the nuclear magnetic dipole moment can provide information on how protons and neutrons are distributed inside the nucleus.

In most experiments, physicists treat electron-nucleus interactions as taking place at (relatively) long ranges. With RaF, that’s not the case. Udrescu describes the radium atom’s electrons as being “squeezed” within the molecule, which increases the probability that they will interact with, and penetrate, the radium nucleus. This behaviour manifests itself as a slight shift in the energy levels of the radium atom’s electrons, and the team’s precision measurements – combined with state-of-the-art molecular structure calculations – confirm that this is indeed what happens.

“We see a clear breakdown of this [long-range interactions] picture because the electrons spend a significant amount of time within the nucleus itself due to the special properties of this radium molecule,” Wilkins explains. “The electrons thus act as highly sensitive probes to study phenomena inside the nucleus.”

Searching for violations of fundamental symmetries

According to Udrescu, the team’s work “lays the foundations for future experiments that use this molecule to investigate nuclear symmetry violation and test the validity of theories that go beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.” In this model, each of the matter particles we see around us – from baryons like protons to leptons such as electrons – should have a corresponding antiparticle that is identical in every way apart from its charge and magnetic properties (which are reversed).

The quantum Zeno effect: how the ‘measurement problem’ went from philosophers’ paradox to physicists’ toolbox

The problem is that the Standard Model predicts that the Big Bang that formed our universe nearly 14 billion years ago should have generated equal amounts of antimatter and matter – yet measurements and observations made today reveal an almost entirely matter-based universe. Subtler differences between matter particles and their antimatter counterparts might explain why the former prevailed, so by searching for these differences, physicists hope to explain antimatter-matter asymmetry.

Wilkins says the team’s work will be important for future such searches in species like RaF. Indeed, Wilkins, who is now at Michigan State University’s Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), is building a new setup to cool and slow beams of radioactive molecules to enable higher-precision spectroscopy of species relevant to nuclear structure, fundamental symmetries and astrophysics. His long-term goal, together with other members of the RaX collaboration (which includes FRIB and the MIT team as well as researchers at Harvard University and the California Institute of Technology), is to implement advanced laser-based techniques using radium-containing molecules.