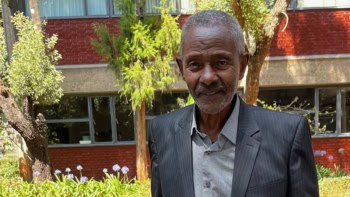

Gordon Brown has recently been accused of bullying staff members. Credit: Downing Street

By Margaret Harris

Workplace bullying has become a hot topic in the UK lately, following allegations that Prime Minister Gordon Brown bullied members of his staff at No. 10 Downing Street. Leaving aside the (substantial) politicking behind these particular claims and counterclaims, the debate seems to hinge on a question that is as relevant to career physicists as it is to career politicians: what, exactly, constitutes bullying?

The UK’s Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS lists several examples of bullying and harassing behaviour. Some of them seem pretty obvious. Any manager — be it a Prime Minister or a PhD supervisor — who makes unwelcome sexual advances or spreads malicious rumours about an employee is clearly bang out of order, and ought to be severely reprimanded or sacked.

But other examples are less clear. “Overbearing supervision” is on the list, as is “ridiculing or demeaning” someone. Neither of them sound like much fun, but different people react differently to criticism, and it’s at least arguable that one person’s “overbearing supervision” is another’s “making sure the job gets done right”.

There are some reasons to believe that academia is particularly prone to bullying, as one commenter on a recent BBC story suggested. The apprenticeship system for PhD students and early-career researchers gives senior academics a lot of power and influence over their junior colleagues. It also makes it difficult for victims of bullying to walk away from a bad situation, because chances are they’ll have to either start over or leave academia entirely.

But I wonder whether there’s something more subtle going on with physics in particular. The fact is that quite a few of history’s great physicists — the people many of us regard as our scientific heroes — weren’t exactly great managers. I enjoy stories about Feynman’s skirt-chasing as much as anyone, but I’d have thought twice about being his PhD student. Bohr frequently drove Heisenberg to tears. And there are plenty of horror stories out there about lesser scientists; my favourite (unconfirmed) one is of a Nobel laureate who allegedly went around urinating in other people’s experiments so that they wouldn’t work.

Can we separate these physicists’ great achievements from their personal flaws? Certainly. But perhaps we should think twice about relating these anecdotes with such gusto. After all, what was Pauli’s famous “not even wrong” jibe if not “ridiculing or demeaning” to the hapless lecturer on the receiving end?