Robert P Crease looks at several books that examine how physics influenced artistic movements

Discoveries in science do not just revolutionize science, but can also exert a deep and lasting impact on the visual arts and on literature. One famous example is the effect that Galileo’s telescopic discoveries had on Milton’s poetry, such as in his depiction of the cosmos in Paradise Lost. Writing about connections between physics and art, however, is difficult to do well. It is easy to draw superficial connections, but hard to establish genuine artistic motivation. Fortunately, several original and substantive books have recently appeared or been reissued that shed new light on how physics influenced art, and illustrate – quite literally – their points well.

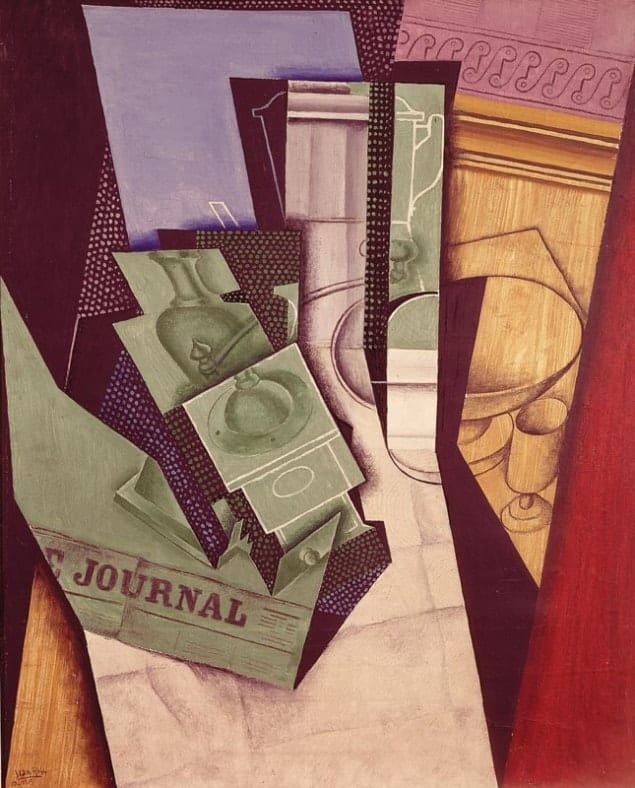

Consider the groundbreaking book The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art by the University of Texas art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson, which was first published in 1983 and has just been reissued with a revised introduction. The book reviews late 19th-century developments in non-Euclidean geometry and the rise of popular interest in these geometries, and then examines this impact on painting in the first half of the 20th century.

Among topics of popular fascination was the ether – the invisible medium that supposedly filled space – which prominent scientists of the day linked with the fourth dimension as containing “the invisible order of things”. Other widely publicized physics discoveries involving invisible structures of reality included the electron, radioactive elements and X-rays. As the science historian Iwan Rhys Morus is quoted in the book as saying, at the start of the 20th century, “the boundaries of the real were so weak”.

Henderson insightfully describes how and why artists listened and responded creatively to these developments. Cubists connected their work most explicitly with the fourth dimension, but they were not alone. Henderson argues that, during the first three decades of the 20th century, the fourth dimension was a “concern common to artists in nearly every major modern movement [in painting]”. The idea of the fourth dimension encouraged artists to dispense with traditional perspective and to experiment with abstraction. It also re-energized their picture of themselves as visionaries able to communicate structures of reality that others could not detect.

For the first two decades of the 20th century, the fourth dimension was popularly associated with space. But after the 1919 confirmation of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and Minkowski’s introduction of the notion of space–time, the fourth dimension began increasingly to be associated with time. This was still true when Henderson’s book first came out in 1983. Since then, the rise of string theory, brane theory and computer graphics have rehabilitated the artistic influence of the spatial interpretation, which Henderson covers in a new, 96-page “reintroduction” in the updated edition of her book.

Surrealist thinking

Modern physics also had a huge impact on the artistic movement known as Surrealism – a topic covered in Gavin Parkinson’s 2008 book Surrealism, Art and Modern Science: Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Epistemology. Parkinson, who is an art historian at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, shows that Surrealist artists responded in a culturally sophisticated manner to the complex political, philosophical, psychological and scientific climate of the time. Claiming to offer “the first comprehensive history, analysis and interpretation” of Surrealism’s enthusiasm for modern physics, Parkinson begins with a sketch of the early history of relativity and quantum theory – a section of the book that, he says, was a “nightmare” to write. However, physicists will find his account, which draws on authoritative histories, both accurate and engaging.

Parkinson then traces how (mainly French) Surrealist artists and authors appropriated the language, concepts and imagery of modern physics in defining and creating their work. One of the first was André Breton, Surrealism’s “chief theorist”, who was soon followed by Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and others. Relativity and quantum mechanics inspired them, Parkinson writes, by showing the utter conventionality of 3D space and ordinary sense perception, and by revealing new aspects of the real.

Breton’s collaborator, Pierre Mabille, wrote in 1940 that physicists are “the legitimate heirs to the tradition of the marvellous”. Indeed, Parkinson argues convincingly that the main currents of modern art cannot be fully understood without knowing the impact of modern physics on the artists involved. Parkinson is not afraid to point out, however, where the artists were “facile”, “engagingly frivolous”, or simply out of their depth in appealing to physics concepts and imagery.

“Like a damp stained wall,” Parkinson writes, “quantum theory can conjure up just about any view of the world if stared at long enough.” But he shows brilliantly why these artists saw what they did, and how they incorporated it into their work. His story ends when Hiroshima began to end the love affair with modern physics, with the break-up culminating in 1958 with a Surrealist manifesto called Expose the Physicists, Empty the Laboratories.

The critical point

Henderson’s and Parkinson’s books document the impact of specific scientific discoveries on particular art movements in a thorough and careful way. Other books that discuss intersections between physics and science in an engaging, though less scholarly, way include Lynn Gamwell’s Exploring the Invisible: Art, Science, and the Spiritual (2002) and Leonard Shlain’s Art and Physics: Parallel Visions in Space, Time, and Light (1991, reprinted 2007). Gamwell is a curator and art historian, and her book is lavishly and cleverly illustrated; Shlain, who died in 2009, was a surgeon by training and wrote as an enthusiast rather than as an artist or scientist.

To me what is fascinating is just how physics exerts an influence on art in so many different ways. It has also influenced sculpture, music and literature – topics that I’ll have to leave to future columns. In the meantime, I welcome your thoughts on the matter.