What is your favourite physics equation and how well would it stand up in the court of public opinion to other equations? That pressing question could soon be answered by the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (PI) in Canada, which has been running a single-elimination tournament that pits famous physics equations against each other. The winners and losers are decided by you, the public.

Modelled on the March Madness US college basketball extravaganza, the tournament started on Monday with 16 equations, which will be winnowed down to a field of eight by the end of this week. Today, you can choose your favourites in two matches. The first sets the second law of thermodynamics against Newton’s law of universal gravitation; and the second puts Maxwell’s equations up against Hamilton’s equations.

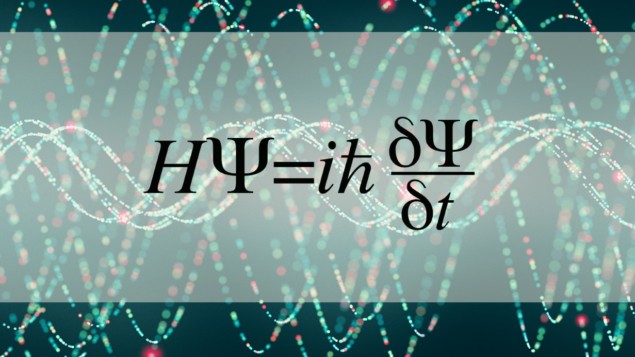

If you have missed voting in the first round, don’t despair. Next week the PI is running the quarter finals – which already has a battle royale set between Schrödinger’s equation and the uncertainty principle.

Closer look

A few weeks ago I wrote about a black hole that never was, and this week’s astronomy snippet is about four exoplanets that never were. Prajwal Niraula of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and colleagues have taken a closer look at some of the thousands of exoplanets that have been discovered in the past 30 years. They have concluded that three (or maybe four) of these objects are probably not exoplanets after all.

Using updated observations, the team reckon that three of the objects – Kepler-854b, Kepler-840b, and Kepler-699b – are bigger than previously thought. The new analysis suggests that the objects are between two and four times the radius of Jupiter – and the team says that this is too big for them to be exoplanets.

The fourth suspect exoplanet is called Kepler-747b and is estimated to be about 1.8 times Jupiter’s radius. While this is on par with the largest confirmed exoplanets, Kepler-747b is relatively far from its star and this means that amount of light it receives is too small to sustain a planet of that size. As a result, the team says that it is doubtful that Kepler-747b is an exoplanet – but not impossible.

So, what are these objects? The team reckons that they are probably small stars that are orbiting larger companions. The team reports its results in the Astronomical Journal.