From lasers and semiconductors to X-rays and the Web, physicists can be credited with seeding numerous technologies that have changed how we live. Hamish Johnston presents five spin-offs from physics research that we predict will most alter our everyday lives over the next 25 years

Predicting the future is a mug’s game, which is why most physicists prefer not to shout too loudly about the possible benefits of their research, even if there is a growing demand from funding agencies to do so. Grandiose, utopian predictions that never materialize always look faintly ridiculous in years to come – have you seen anyone recently flying to work on a nuclear-powered jet-pack?

But with this being the 25th anniversary of Physics World, it is only right that we should set ourselves up for a fall by picking the five physics spin-offs we expect to make the biggest difference to humanity over the next few decades. And while there are plenty of spin-offs that will aid science, our five choices are those that will, we feel, do most to improve the everyday lives of ordinary people around the world.

Of course, we expect to get a few of them wrong. And there are bound to be one or two seemingly mundane discoveries that we have missed, yet will catapult to fame and fortune in the next few years. So without further ado, let’s begin with our first choice – a medical treatment that today can only be done at 40 or so facilities worldwide but that, we reckon, will soon be found at every major hospital around the globe.

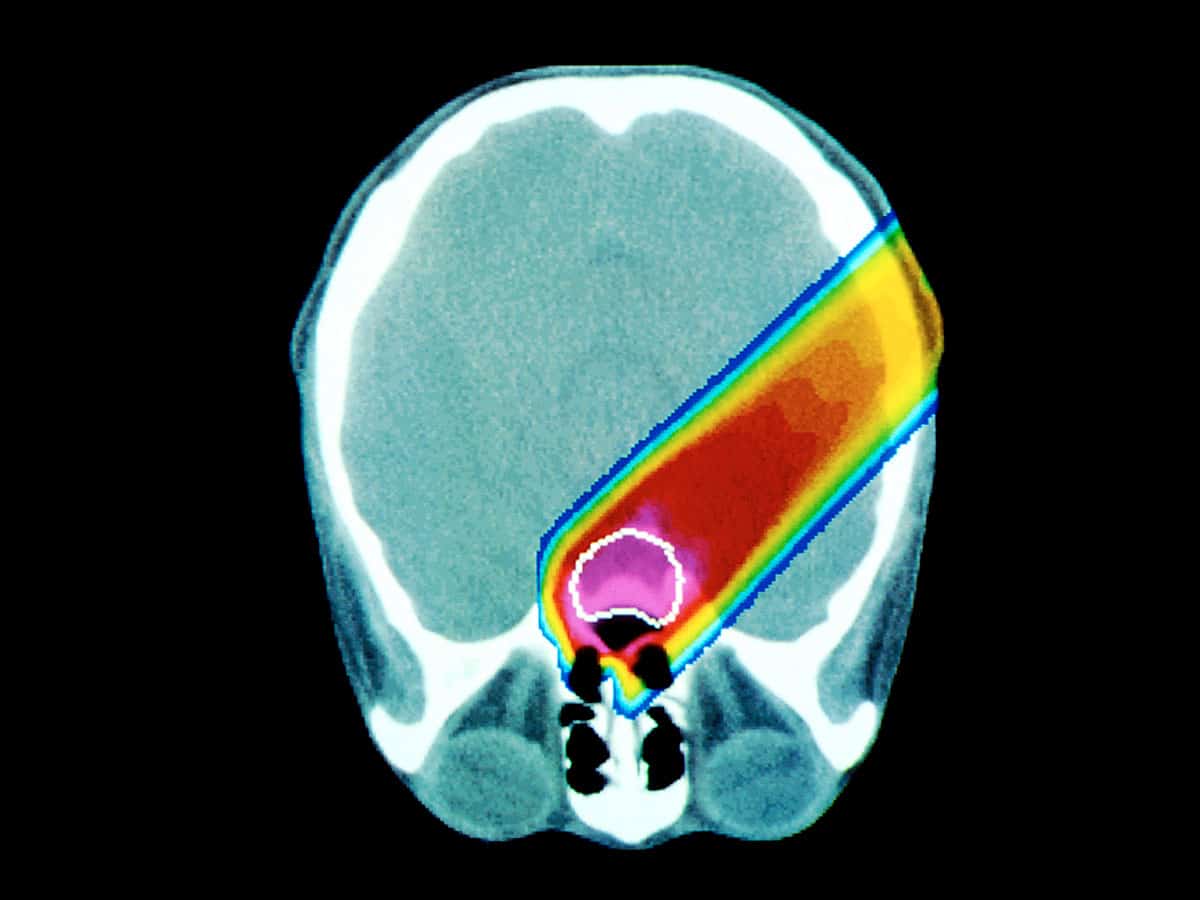

A better beam

That treatment is hadron therapy, which exploits the fact that beams of protons and other hadrons can almost magically penetrate human tissue before releasing their energy at a well-defined depth. Hadron beams can therefore kill tumour cells while sparing healthy tissue, making them ideal for treating certain cancers – notably the potentially lethal eye cancer ocular melanoma – because the patient suffers less and the success rate is higher. Gamma rays, X-rays or electrons, in contrast, tend to dump their energy over a much greater volume.

Particle therapy has emerged as a by-product of high-energy physics – in fact, the first treatment took place at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 1954 – but making it more widely available is a challenge. The snag is that the accelerators currently used to create beams of protons and other heavy ions are large and expensive, and the gantries that steer the beam across a tumour are the size of a small house. But one solution that could put particle therapy within the reach of most hospitals is laser-driven acceleration, which involves firing a very short yet intense laser pulse into a jet of gas, thin foil or thicker target.

Particle therapy has emerged as a by-product of high-energy physics, but making it more widely available is challenging

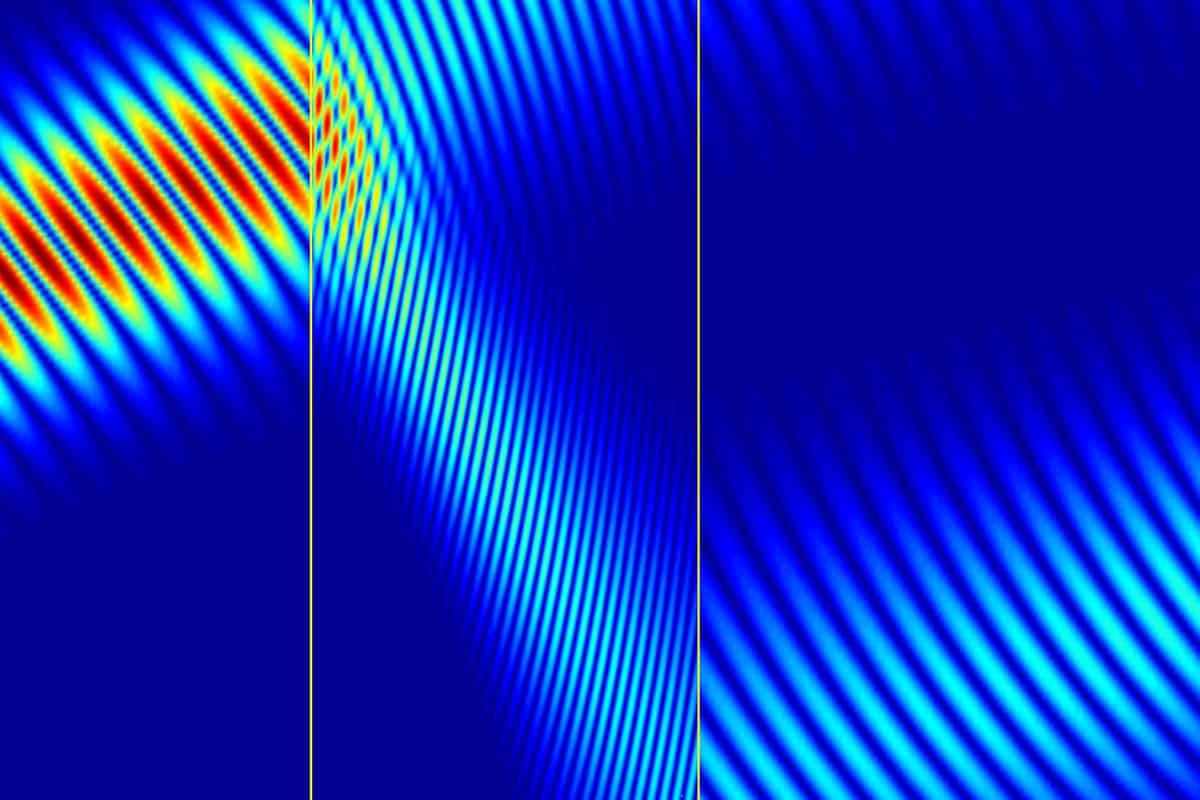

As the intense pulse travels through the target, it rips nearby electrons away from the positive nuclei, thus creating a huge electric field gradient in its wake. This field has a large accelerating potential that can be thousands of times that of a conventional accelerator. A laser-driven hadron accelerator can therefore, in principle, be relatively compact. Table-top lasers have already been used to accelerate protons to tens of mega-electron-volts, approaching the 70 MeV needed to treat ocular cancer. However, we need to find ways of boosting their energy to 200–300 MeV to kill tumours lying deeper within the body.

Commercially available laser systems that can deliver such energies should be available in about 10 years, although it will probably take a further decade or so before they become routinely used to treat patients in hospitals. One problem with laser acceleration is that it delivers particles in pulses, rather than as a continuous beam. Techniques will therefore have to be devised to ensure the pulses are intense and numerous enough that patients get enough of a dose without having to lie perfectly still for long periods. In fact, the pulses could be a virtue as the magnets needed to scan the proton beam across a treatment area would then not have to be as big.

And if lasers do not bring hadron therapy to every hospital, there are other options, such as fixed-field alternating gradient accelerators. They are being developed at Daresbury Laboratory and elsewhere, and could also lead to compact devices suitable for cancer treatment.

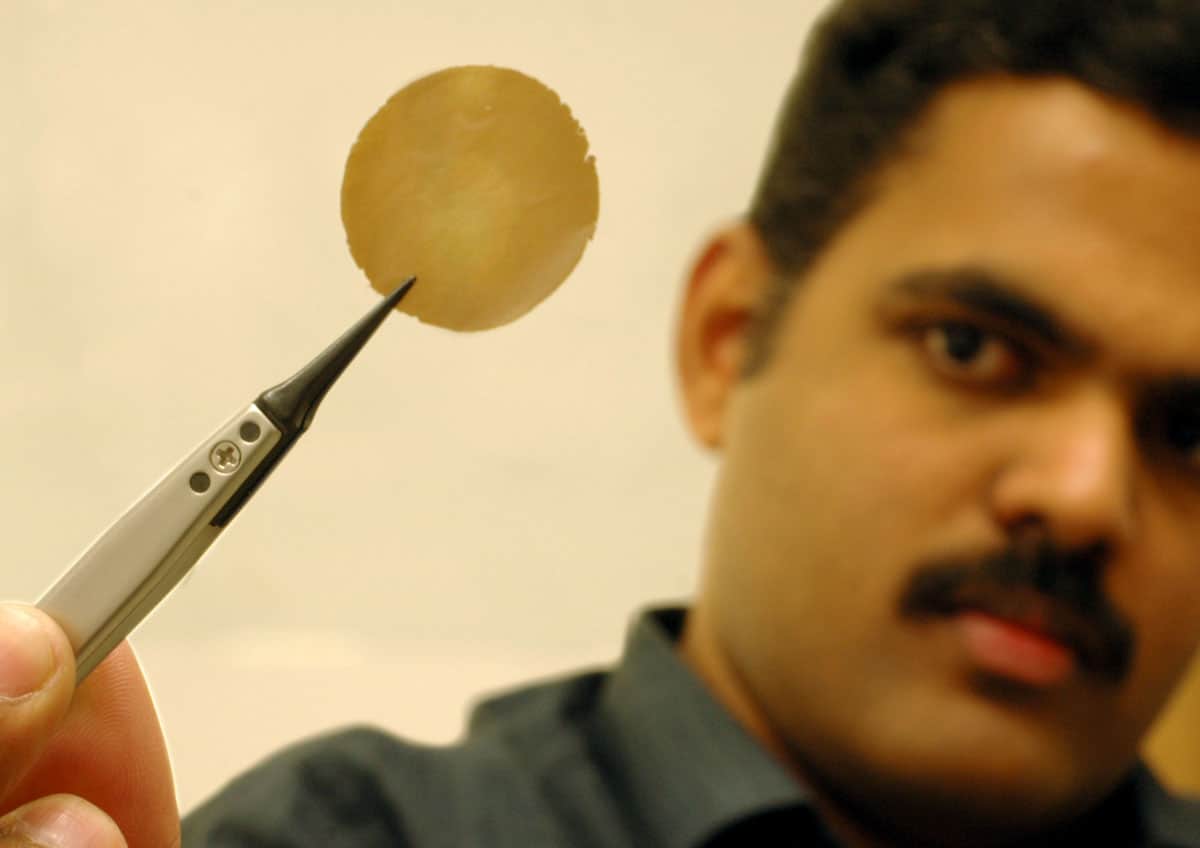

Some like it thin

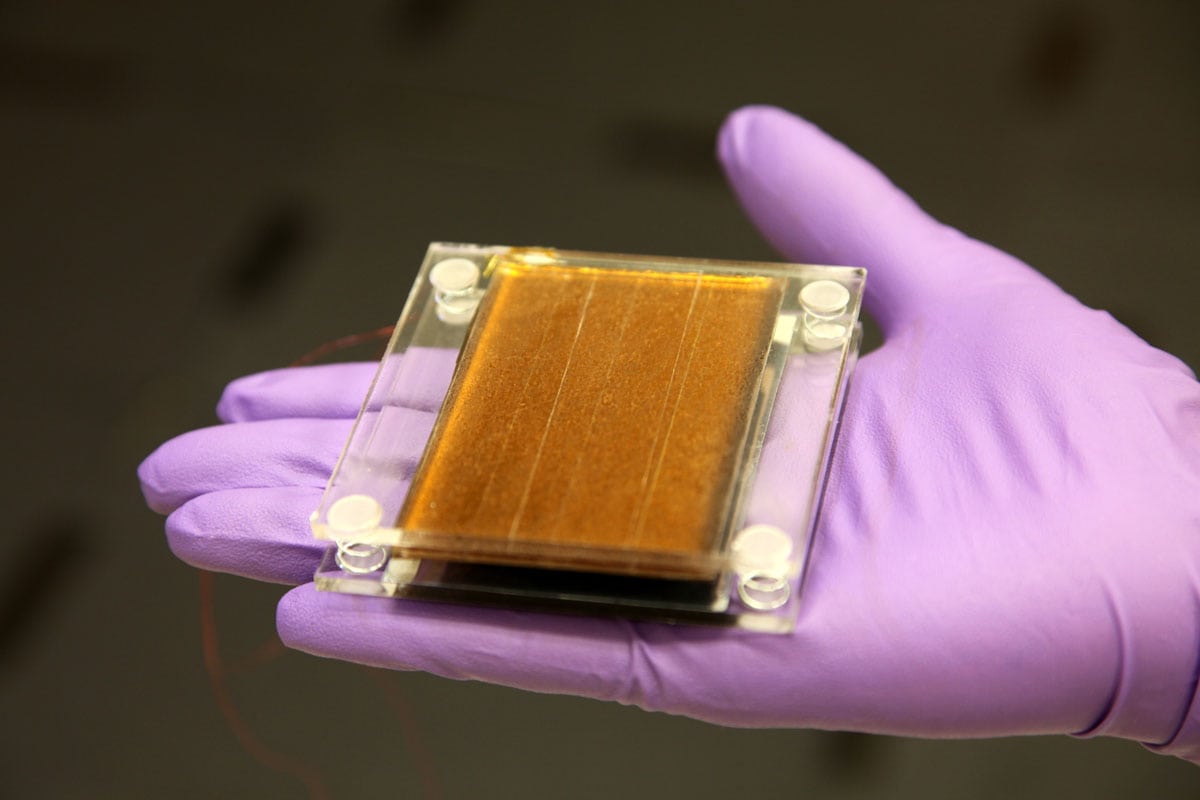

While laser-driven hadron therapy is likely to be of most benefit to people in rich nations, our next spin-off could have massive implications for those in the developing world. It involves a material that was first isolated just nine years ago by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov at the University of Manchester. That substance is, of course, graphene. Much of the hype surrounding this 2D honeycomb of carbon atoms has focused on its extraordinary electronic properties – who could resist the lure of an ultrathin bendable smartphone? But we think that another of graphene’s physical properties could be more important still. It turns out that despite being just one atom thick graphene appears to be completely impervious to almost every liquid and gas. By drilling holes of the appropriate size in graphene – or creating membranes of graphene flakes stuck together with just the right sized gaps between flakes – the material can be used as a selective filter.

In 2012 Geim and colleagues found that membranes made from millions of flakes of graphene oxide that had been stuck together allow water to easily pass through – yet the membranes are impervious to every other liquid or gas tested. Indeed, water was found to flow through the membrane 10 billion times faster than helium, which itself is rather good at diffusing through solids.

The application of such graphene membranes is obvious: they could be the ultimate water purifiers and could someday create drinking water from the sea. But such graphene-based membranes could have other applications as well, such as separating molecular species in a mixture, shielding people from dangerous toxins or making more efficient electricity-generating fuel cells.

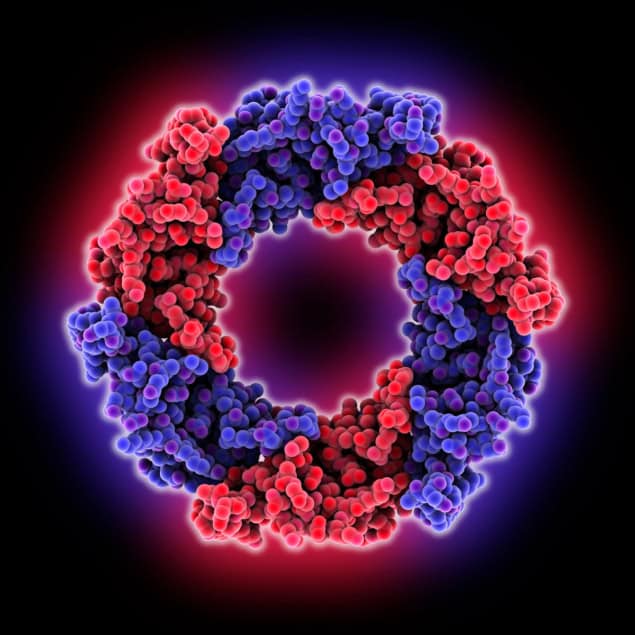

But while cheap and effective water purification could be an early spin-off from research into graphene, this “wonder material” could have many other applications in biology and medicine too. One promising idea is to read the base sequences of DNA by drawing these protein chains through tiny nanometre-sized holes drilled into graphene, the electrical properties of which change depending on which base happens to be in the pore at any one time. Such graphene “nanopores” could even be engineered to mimic the plethora of pores inside living cells or to craft artificial systems that recreate the incredible filtering abilities of the cell wall.

Being strong, flexible and – as far as we know – biocompatible, graphene could also be used as the basis of new kinds of prosthetic limbs. Earlier this year, for example, physicists in Germany showed that graphene transistors can generate an electrical signal in response to changes in the concentrations of ions that occur when cultured nerve cells fire. Work like this could help us to build artificial limbs that are wired directly into the human nervous system using graphene electronics as the interface.

Quantum calculations

Strengthening the links between complicated, messy biology and the neat reductionist world of physics is the basis for our next revolutionary spin-off. For the past decade or so, the new discipline of quantum information has grown by leaps and bounds. Ultra-secure quantum-cryptography systems are already being used by banks and other institutions keen on secrecy. Physicists can transmit quantum information a hundred or so kilometres through the air, and there are serious proposals to make a quantum link between ground and satellites in space.

The possibilities of quantum computers, however, are even more intriguing. Such devices, which would exploit superposition, entanglement and other quantum phenomena to perform super-fast calculations, have the potential for some amazing feats. But there is one particular thing that a quantum computer can do much better than a conventional computer – and that is to solve the Schrödinger equation for systems as large as a molecule, without resorting to the messy approximations that are usually needed to describe even the simplest molecules.

This would involve taking a collection of quantum bits, or “qubits” – say trapped ions – and manipulating both their internal properties and the interactions between them to simulate the atoms, and the forces between them, in a molecule. In the case of ions, this manipulation could be done by adjusting electric and magnetic fields applied to the ions or by shining laser light on them. Researchers would need about 100 qubits to do quantum simulations that can compete with today’s supercomputers. Although today’s best systems have tens of qubits, our control over the quantum world is improving so rapidly that working “quantum simulators” could be with us in a decade or so.

Algorithms for such simulators have, in fact, already been developed for calculating chemical reaction rates and how proteins fold. If put into practice, they could help with the design of new drugs by allowing chemists to calculate more accurately the properties of candidate molecules and slash the time it takes to determine which would work best. Quantum simulators could also be used to understand the process by which DNA protects itself from the gene-damaging glare of sunlight, which could help prevent skin and other cancers.

Simulators could even help us to understand how photosynthesis occurs and thereby let us build artificial systems that mimic the efficient energy harvesting of plants or serve as new sources of sustainable energy. Quantum simulations would also help chemists get a better handle on how enzymes work, which could be a boon to the chemical industry. Indeed, quantum simulation looks set to be one of the most important tools that physicists have created for the rest of science.

Seeing more clearly

Our next big spin-off could also boost our understanding of biological processes by giving us a new way of seeing with light. Light is, of course, a wonderful thing as it can be guided and focused using simple lenses and fibres, capturing images of objects that are either too small or too far away to be seen with the naked eye. Moreover, many atomic and molecular transitions occur at optical wavelengths, which is why light – from the infrared to the ultraviolet – lies at the heart of a vast range of spectroscopic techniques.

But there is one major drawback to light as a probe of atoms and molecules: light of a certain wavelength cannot be used to discern an object smaller than about half that wavelength. Even for ultraviolet light, this “diffraction limit” is about 50 nm, or roughly the size of a large protein molecule. Electron microscopy can get round this resolution problem because the wavelengths of electrons can be much shorter than light. But it usually requires samples to be prepared in a way that can alter them, which is a problem for fragile biological systems.

Over the past decade or so, however, physicists have devised a way of getting around the diffraction limit and obtaining images of objects that are much smaller than optical wavelengths. The technique does not involve the familiar “far-field” light that is scattered or transmitted by an object and observed some distance away from it. Instead, it exploits the “near-field” or “evanescent” light that contains detailed sub-wavelength information about an object.

This light, which decays exponentially over a distance shorter than the wavelength of the light itself, cannot be gathered and focused using conventional optics. But in 2000 John Pendry of Imperial College London predicted that artificially engineered metamaterials with a refractive index of less than zero could be used to create a “superlens” that could gather and focus the evanescent light before combining it with the far-field light to create an image of the object. If the lens were “perfect” and gathered all the light, it could be used to create an image with infinite resolution. But even if only some of the light were captured, a superlens could still probe distances significantly below the diffraction limit.

Superlens-powered “nanoscopes” look set to fundamentally alter how we view the very small

The challenge with making negative-index metamaterials is that the index of refraction has both an electric and a magnetic component, both of which have to be less than zero. And, while the first rudimentary superlens-powered “nanoscopes” have already been made using metamaterials with the appropriate electrical components, making a material with the right magnetic response seems to have stalled over the past few years. Still, we think such nanoscopes look set to fundamentally alter how we view the very small – from protein folding and DNA replication to seeing how viruses invade healthy cells. So perhaps the superlens will find a cure for the common cold at last.

Power on the go

Our final spin-off concerns energy – and specifically the stuff that powers the growing number of smartphones, tablets and other portable devices that we use while on the move in our daily lives. These are mostly run by lithium-ion batteries, but boosting battery capacity has proven very difficult. If we are moving, however, why not harvest some of that kinetic energy to power all our gadgets? Harvesting is most efficient when it harnesses repetitive motion such as walking, and the best estimate for the maximum rate at which mechanical energy can be converted to electrical energy – without impeding the walker – is 11 W. That, coincidentally, is about the same as today’s ubiquitous USB charger.

Researchers have already made a device – designed to be fitted into a shoe – that can fully charge a mobile phone in about 10 hours. While most of us do not regularly walk for such long periods, a phone user could at the very least keep their phone battery topped up using such a system. The “shoe charger” has been built by a team led by Zhong Lin Wang at the Georgia Institute of Technology, who is an advocate of energy harvesting from triboelectricity – commonly known as static electricity.

Normally the bane of engineers working in fields as diverse as aeronautics, microelectronics and textiles, triboelectricity is generated when two different materials (one electron-loving and the other electron-repelling) are rubbed together and then moved apart. The result is two oppositely-charged surfaces that create a voltage that drives a current. But triboelectric generators do not just have to be fitted into shoes. A jacket, for example, could produce 10–20 W from human motion – while a triboelectric flag flapping in the breeze could harvest 30–50 W.

But who would want a triboelectric flag and clothes? The most immediate beneficiaries are sure to be infantry soldiers, who are currently burdened by massive battery packs weighing up to 10 kg that they need to power a myriad of electronic devices from night-vision goggles to GPS and communications systems. Triboelectric systems could also be used to power the growing number of medical implants and prosthetics that currently run only on batteries.

While all of these innovations have come from blue-sky research, they will probably come to fruition in very different ways. Laser-driven proton therapy will be developed by large teams of physicists, cancer specialists and medical-equipment makers, whereas the first commercial shoe charger could be created in someone’s garage. And to make a difference in our lives, all of these concepts must survive the “valley of death”: the gap between making a scientific discovery and turning it into a practical product. We are confident that at least some of our top five will make it across.