The Ukrainian city of Kharkiv was a major target during the first days of the Russian invasion and, as the Russian army advances, it continues to face attacks by drones and missiles. But when he travelled to Kharkiv in November 2023, photographer Eric Lusito discovered a resilient community of scientists doing everything in their power to continue their research

Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, has a long history as a world cradle of physics. The first experiments in the Soviet Union on nuclear fission were conducted there in the 1930s, and in 1932 the future Nobel-prize-winning physicist Lev Landau founded an influential school of theoretical physics in the city. Over the years, Kharkiv has been visited by influential scientists including Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac and Paul Ehrenfest.

Kharkiv is still home to many research institutes, but, located just 30 km from the Russian border, the city has been heavily damaged and suffered hundreds of casualties since the Russian invasion that began in February 2022. In the past week, advances made by the Russian forces have put the region under increased pressure, with thousands of civilians fleeing away from the border towards Kharkiv.

I first travelled to Kharkiv in November 2021 as part of a photography project documenting Soviet-era scientific facilities. The Russian army was massing at the border, but I was nevertheless stunned when, having returned home to France, I heard the news of the invasion.

The day after I arrived, explosions rang out in the city centre

I considered abandoning my project, but I felt compelled to document what was happening and in November 2023, I returned to Kharkiv. Though the Ukrainian counter-offensive had pushed back the Russian forces, the city was nevertheless plunged into darkness, the streets deserted. The day after I arrived, explosions rang out in the city centre.

For two weeks, I photographed Kharkiv’s scientific facilities, many of which had been destroyed or badly damaged since my previous visit. I also interviewed and photographed scientists who were continuing to perform their research despite the ongoing war. As the situation in Kharkiv becomes increasingly critical, the pictures I took stand as a record of the effects of the conflict on the people of Ukraine.

Department of Solid State Physics and Condensed Matter, Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, November 2021 and November 2023

Even when I was there in 2021, visiting the old cryogenics laboratory of the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology (KIPT) was like stepping back in time (photo 1). Founded in 1928 as the Ukrainian Physics and Technology Institute, KIPT is one of the oldest and largest physical science research institutes in Ukraine. New facilities have been built on the outskirts of the city, but the original buildings are still standing and, because of the historical value of the site, a project is underway to convert them into a museum.

When I returned in 2023, the corridors were silent, the heating was shut off and all the doors were closed. However, a few of the offices were still occupied by researchers in KIPT’s Department of Solid State Physics and Condensed Matter (photos 2, 3). During my visit, I also met students from the Kharkiv National University who were visiting with their teacher, Alexander Gapon (photo 4). Their faculty had been damaged in the early days of the fighting, and they had moved lab classes to KIPT so that teaching could continue.

Plasma Physics Institute, Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, November 2023

The Plasma Physics Institute houses two huge stellarators for studying nuclear fusion. These machines confine plasma under high magnetic fields (photo 5), creating the hot, dense conditions necessary for nuclei to fuse.

I met Igor Garkusha, the director of the institute, who showed me where the roof of the facility had been pierced by projectiles during the early days of the Russian invasion. Debris was still scattered everywhere and, in the room housing the stellarators, he held up a piece of shrapnel (photo 6). The roof played its protective role and the stellarators have not suffered any damage, but with research temporarily halted, Garkusha worried that they were at risk of losing skills.

“I never thought the Russians would wage war on us because I have a lot of family and friends on the other side,” Garkusha said. “I attended a nuclear fusion conference in London organized by the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) in October. There were Russian scientists whom I’ve known for 20 or 30 years, and not one of them spoke to me.”

The Institute for Scintillation Materials, Kharkiv, November 2023

“I can’t complain: we get a lot of orders,” says Borys Grynyov (photo 8), director of the Institute for Scintillation Materials. Scintillation crystals, which emit light when exposed to radiation, are a vital component of particle detectors, and even though some of its buildings have been destroyed, the institute continues to participate in CERN research programmes.

For several months at the beginning of the war, around 50 people – members of staff, and their families, lived in the basement of the facility. The teams were eventually able to move the equipment to better-protected rooms, which allowed the production of the scintillation crystals to resume (photo 9).

Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute, November 2023

At around 5.30 a.m. on 19 August 2022 a missile struck a university building of the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute (photo 10). From 8 a.m., Kseniia Minakova, head of the optics and photonics laboratory, searched through the rubble for what could be salvaged. Much of the equipment had been destroyed, but she and her colleagues found some microscopes, welding equipment and computers. After a few days, heavier equipment such as vacuum pumps could be evacuated.

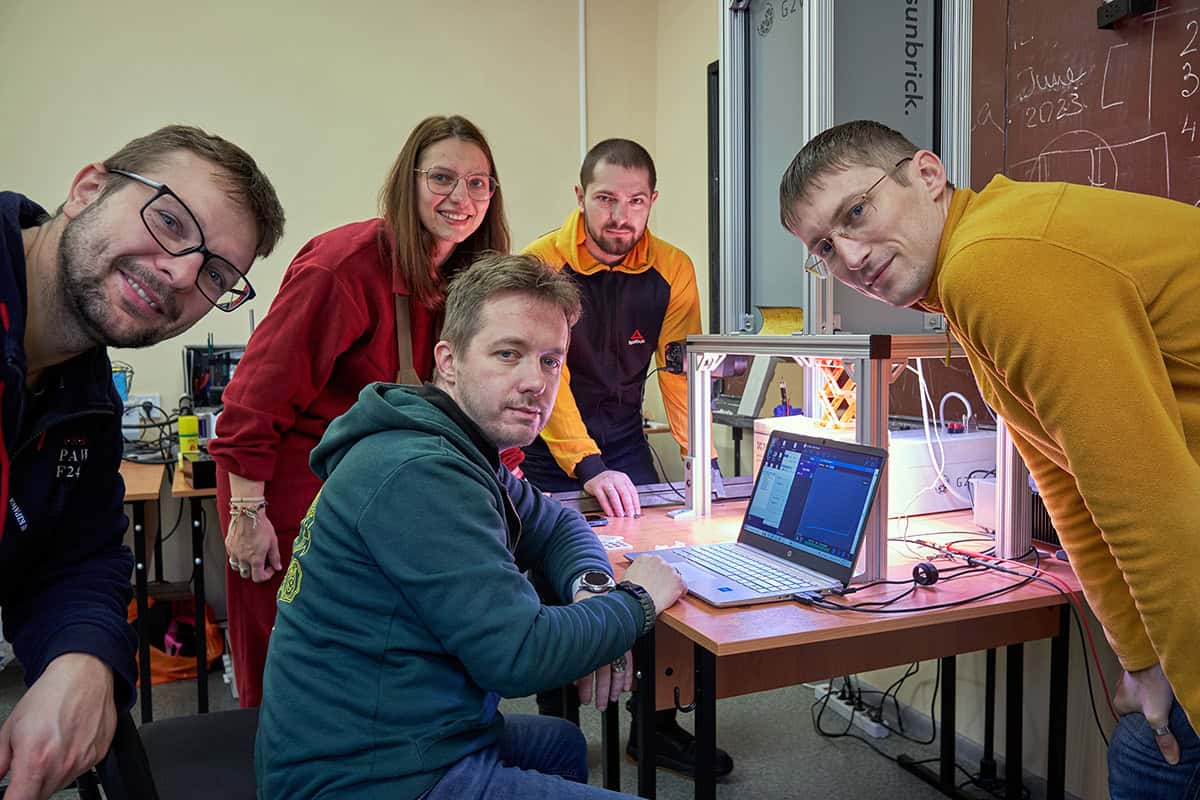

I met Minakova at the institute, where she showed me her small temporary laboratory (photo 11). Her research is dedicated to solar energy and improving heat dissipation in photovoltaic systems. To enable Minakova’s team to continue working, Tulane University in the US, where they have collaborators, donated photovoltaic cells as well as a new 3D printer, screens, oscilloscopes and other equipment.

But what she was most grateful for was at the back of the room, where her team was huddled around a solar simulator donated by a Canadian company (photo 12). “I explained to them what I needed and they came up with a technical solution for our laboratory and completely assembled a new installation for us from scratch. This equipment is worth $60,000!” exclaimed Minakova.

In 2023 she was appointed ambassador of the Optica foundation and a finalist for the L’Oréal-UNESCO “For Women in Science” prize. She has received several offers to work abroad. “I turned them down. My place is here, in Ukraine. If everyone leaves, who will take care of rebuilding our country?”