By James Dacey

Have you come across new research, utterly failed to realise its significance, then the penny drops shortly afterwards? Well it happened to me this week. On Monday, I stumbled across a new research paper in Nature about the behaviour of quasi-particles in a semiconductor and quickly dismissed it as niche physics. However – a little sniffing around the edges and a few phone-calls-to-experts later – I’m beginning to realise the significance this paper may hold for our understanding of Bose-Einstein condensates and superfluidity.

The research in a nutshell: a group of physicists led by Alberto Amo of Madrid’s Autonomous University have observed polaritons — quasiparticles merging photons with excitons — travelling without resistance in a semiconductor microcavity; thus behaving like a superfluid; thus potentially being the first Bose-Einstein condensate in a system out-of-equilibrium.

But I think the research still needs some historical context…

Bose-Einstein condensation was first predicted back in 1925 when Einstein — building on the work of Satyendra Nath Bose — predicted that when weakly interacting atoms are cold enough they drop into their ground state and the individual waveforms merge to create a single quantum state.

In the 1950s theorists began to link the strange “superfluid” behaviour observed in helium-4 at temperatures below 2 K with the — now established — theory of Bose-Einstein condensation. They realised the zero viscosity was linked with the zero entropy, which was a feature of the theorised condensates. The problem was that Einstein’s theory had applied to weakly interacting particles whereas the observed ‘superfluidity’ in helium-4 involved strongly interacting ones.

It was only in 1995 that separate research groups at Colorado and MIT created Bose Einstein Condensates in gases of weakly-interacting rubidium and sodium atoms respectively. They managed this by carefully cooling these gases to microkelvin temperatures and then shared a Nobel Prize for their efforts.

What this latest research offers is a new Bose-Einstein condensate, which — with further development — could lead to superfluidity at ‘everyday’ temperatures.

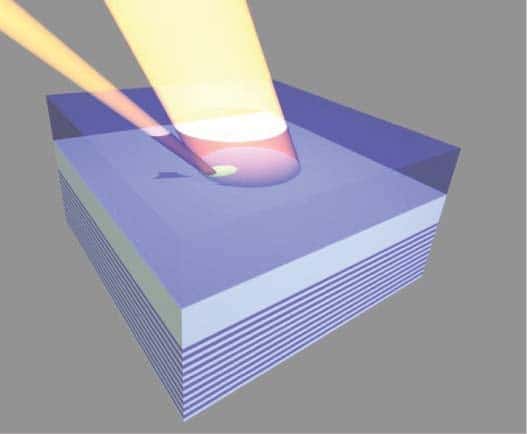

This new condensate comprises polaritons which are “quasiparticles” formed from the coupling of photon with an exciton (a bound state of an electron and a hole) in a semiconductor material. These particles are short-lived (picoseconds) and can be created by firing a laser at microcavities in semiconductors which serve to confine excitons within a quantum well. Resultant polaritons flaunt properties of both light (miniscule mass ~0.0001 of an electron), and the exciton (weak polariton-polariton interaction).

Polariton condensates were first suggested in 2006 and then confirmed experimentally in 2007 by firing a laser at a microcavity and observing the created polaritons acting as a coherent whole.

Amo and his colleagues have come up with a new method for pumping microcavities with a coherent stream of polaritons, rather than injecting them like the 2007 effort. The continuity of flow increases both density and velocity of polaritons which led

to the condensate flowing around microcavity defects without disturbance — like a superfluid.

David Snoke of the University of Pittsburgh said this result is a great advance in our understanding of BEC’s which “calls into question the definition of a ‘superfluid’”. Jonathon Keeling — a low temperature physics exert from Cambridge University — told me this experiment could eventually lead to new applications like highly efficient switches in optics.