“Stephen had an especially broad legacy,” said Imperial’s Fay Dowker, citing Hawking’s commentary on fields ranging from cosmology to condensed matter and information science. Of course, his legacy reaches still wider than that, as felt evident climbing the stairs to the Science Museum’s Imax auditorium for the launch of his last book, led by an elderly lady leaning heavily on her stick while a young girl of school age brought up the rear. Hawking kindled an interest in physics in young and old, academic and lay, and the excitement over the this new publication was tangible.

Stephen Hawking’s final book: a review of Brief Answers to the Big Questions

Hawking’s daughter Lucy Hawking explained that this final book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions – published posthumously and completed through the collaboration of family, friends and the Stephen Hawking Estate – aims to bring together the clearest and most authentic answers to the questions he was asked most regularly. This may sound like a disclaimer for novelty, but the fundamental nature of the questions posed, which includes “Is there a God?” and “How did it all begin?”, as well as his passion for communicating science in a way his daughter described as “accessible, engaging, enlightening, and in a way that people can relate to”, should make it a tantalizing read. Asked what question was most important to him, she replied: “Will people understand my answers?”

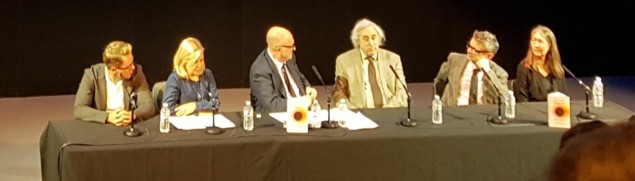

The panel at the launch, chaired by the Science Museum’s director of external affairs Roger Highfield and introduced by the chair of the trustees of the museum Mary Archer, included both Lucy Hawking and her younger brother Timothy Hawking, as well as frequent co-authors Malcolm Perry and Andrew Strominger, and his former PhD student Fay Dowker. In addition to the book, we were invited to learn more about Hawking’s final paper, co-authored by Perry and Strominger, which sheds further light on what are now believed to be not quite so black holes. It should raise no eyebrows to hear that black-hole theory reneges on yet another previously held maxim – as Strominger pointed out, black holes are complex, even for the likes of Albert Einstein who he describes as writing a “spectacularly wrong paper” on the subject 25 years after they had first been discovered. Like any other tricky endeavour, explanations of black holes are not necessarily perfect at first attempt.

Stephen Hawking’s ‘final paper’ on hairy black holes hits the headlines

Black holes provided a lifelong fascination for Hawking, whose life was spent “travelling across the universe, inside my mind”. The Cambridge physicist wrote these words in the opening chapter of Brief Answers to Big Questions, although they echo the media’s oft-pedalled image of a scientist physically incapacitated by disease yet freed through an intellect of supergalactic capacity to explore unfathomable depths of the cosmos. (Whether this image is a true reflection of the man is explored in Margaret Harris’s book review “In search of the real Stephen Hawking“.)

Those familiar with one of Hawking’s biographies will already know that the physicist had a deeply human side. Having his family on the panel, visibly emotionally affected at the sound of his voice in the brief clips played, emphasized that Hawking was a father as well as a great mind, someone ready to engage with family high jinks as much as questions of the universe. His son Timothy Hawking told launch attendees that his father had a lively sense of humour and hated to be alone. Asked what he might think of his current religious environment in Westminster Abbey, given his view that “the simplest explanation is that there is no God”, Lucy Hawking suggested that he would be happy to be in same company as Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin.

Importantly, Hawking was ready to concede errors in prior work. “He was prepared to change his mind if you could convince him with rigorous calculation,” said Dowker, and there have been numerous examples of his willingness to put data before dogma. Hawking gives his own delightful example in Brief Answers to the Big Questions in the section on time travel, where he describes how he sent invitations to a party after the event, only to be disappointed that no-one had travelled back in time to attend – even though this would contradict his understanding of general relativity.

While highlighting his concerns on the current challenges facing the world, Lucy describes his outlook at the end of his life as still very optimistic “because he believed in human beings”. The humanitarian flavour of his science communication explains much of his appeal to non-specialists, and this final book – which straddles societal, philosophical and scientific interests – epitomizes the reach of his ideas, and the ability of his work to spark genuine curiosity and excitement in all his readers.