The influx of wealth into a neighbourhood can increase house prices through a process dubbed “property gentrification”, but could changes in climate also modify residential markets? In a recent study, researchers at Harvard University, US, focused their attention on Miami-Dade County, Florida – an area with exposure to sea level rise – to explore market mechanisms for “climate gentrification”.

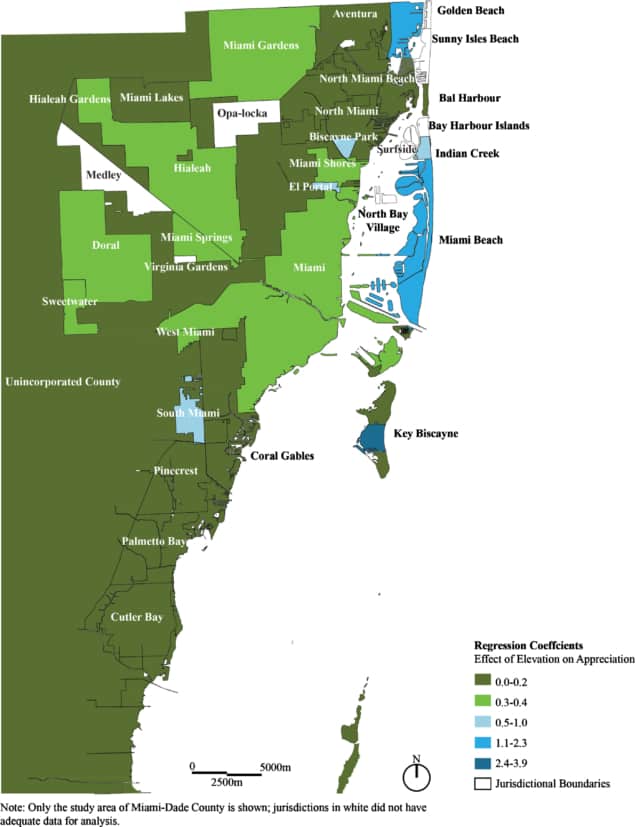

The team investigated whether the rate of price rise for single-family properties in Miami-Dade County has links to their elevation.

“It is speculated that comparatively high- and low-elevation properties in Miami-Dade County will be more or less valuable over time by virtue of a property’s capacity to support habitation in the face of nuisance flooding and relative sea level rise,” writes the team in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).

Jesse Keenan and colleagues examined whether the rates of price appreciation in the lowest elevation cohorts have kept up with the rates of appreciation of homes at higher elevations since the year 2000, when environmental conditions seem to have become more challenging for the region.

Properties in the 2–3 metre and 3–4 metre above sea level cohorts have had slightly higher rates of price appreciation than the 1–2 and 0–1 metre cohorts, the team found. And interviews with local officials, researchers, real estate developers, investors, financiers, residents and activists, suggest a growing awareness of what the scientists term the “elevation hypothesis”.

“In light of accelerated sea level rise, these preferences may become more robust and may lead to more widespread relocations that serve to gentrify higher elevation communities,” writes the team.

The result points to a pathway for climate gentrification to disrupt economically vulnerable communities at higher elevations. Families living at lower elevations could also experience financial hardship through a deterioration in environmental conditions.

“This would be primarily due to the increased costs of insurance, property taxes, special assessments, property repairs, transportation and consumer goods, as well as a loss in overall productivity – for example, from sitting in traffic in water-clogged streets,” note the researchers.

The group also has concerns on the climate gentrification front about the unintended consequences of making public investments in the engineered resilience of buildings and infrastructure.