By James Dacey

The story of young brain-tumour patient Ashya King has gripped the British public over the past few weeks, with every twist and turn covered extensively in the media. In a nutshell, the five year old was removed from a hospital in Southampton at the end of August by his parents, without the authorization of doctors. They wanted their son to receive proton-beam therapy, which was not offered to them through the National Health Service (NHS). The family went to Spain in search of the treatment, triggering an international police hunt that subsequently saw the parents arrested before later being released.

The drama was accompanied by a heavy dose of armchair commentary, with Ashya’s parents, the hospital in Southampton and the police all receiving both criticism and praise. Even the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, got caught up in the affair, as he offered his personal support to the parents. To cut a long story short, Ashya’s parents finally got their wish and they have ended up at a proton-therapy centre in the Czech Republic where their son’s treatment begins today.

But what is proton therapy? It is a relatively new medical innovation that shows great promise in the treatment of cancer, though it is only currently available in certain countries. Beams of protons can be directed with precision at tumours in the body – allowing the energy to destroy cancer cells, while causing less damage to the surrounding tissue than is possible with conventional radiation therapies. The treatment, however, is only really useful in specific cases of cancer, such as where is vitally important that surrounding structures are not damaged. And because it is relatively new, there is less information available about how effective it is compared with more established treatments.

At the beginning of last year, we published this short film that introduces the basics of the treatment. Recorded at a proton-therapy centre at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in the US, the film looks at how proton therapy can be combined with positron-emission tomography (PET) imaging to enable doctors to fire a beam of protons at a tumour then check whether their beam has hit the intended target.

[brightcove videoID=ref:phw.live/2013-03-21-MGH-proton-PET-therapy/1 playerID=106573614001 height=268 width=390]

According to the Proton Therapy Centre in Prague, Ashya will have 30 irradiation visits – the first 13 will focus on the spinal cord to ensure the tumour is not spreading to the surrounding area, and the next 17 visits will focus onto the tumour volume itself. “There is a 70 to 80 per cent survival rate for the condition such as Ashya has and there is now every reason to hope that he will make a full recovery,” says Dr Ondrova, his attending doctor.

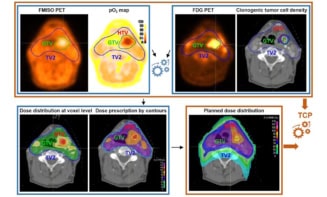

The pinpoint accuracy of proton therapy can, though, be a disadvantage – for example, treatment plans can be prone to more uncertainties that come from dose calculations, or from patients losing weight during a period of treatment. In a separate film recorded at the MGH, we looked at how the doctors administering proton therapy to cancer patients are striving for more effective ways of drawing up treatment plans. For help, they are looking to mathematics in a new approach called multicriteria treatment planning.

[brightcove videoID=ref:phw.live/2013-03-27-MGH-multicriteria/1 playerID=106573614001 height=268 width=390]

For more information on proton therapy, take a look at these news articles from medicalphysicsweb.org, which – along with Physics World – is published by the Institute of Physics.

• Proton therapy shows clinical promise

• Proton therapy reduces second cancer risk

• 4D imaging guides proton therapy