In the quantum world, observing a particle is not a passive act. If you shine light on a quantum object to measure its position, photons scatter off it and disturb its motion. This disturbance is known as quantum backaction noise, and it limits how precisely physicists can observe or control delicate quantum systems.

Physicists at Swansea University have now proposed a technique that could eliminate quantum backaction noise in optical traps, allowing a particle to remain suspended in space undisturbed. This would bring substantial benefits for quantum sensors, as the amount of noise in a system determines how precisely a sensor can measure forces such as gravity; detect as-yet-unseen interactions between gravity and quantum mechanics; and perhaps even search for evidence of dark matter.

There’s just one catch: for the technique to work, the particle needs to become invisible.

Levitating nanoparticles

Backaction noise is a particular challenge in the field of levitated optomechanics, where physicists seek to trap nanoparticles using light from lasers. “When you levitate an object, the whole thing moves in space and there’s no bending or stress, and the motion is very pure,” explains James Millen, a quantum physicist who studies levitated nanoparticles at Kings College, London, UK. “That’s why we are using them to detect crazy stuff like dark matter.”

While some noise is generally unavoidable, Millen adds that there is a “sweet spot” called the Heisenberg limit. “This is where you have exactly the right amount of measurement power to measure the position optimally while causing the least noise,” he explains.

The problem is that laser beams powerful enough to suspend a nanoparticle tend to push the system away from the Heisenberg limit, producing an increase in backaction noise.

Blocking information flow

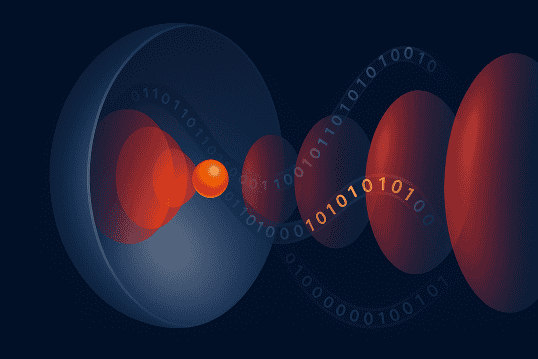

The Swansea team’s method avoids this problem by, in effect, blocking the flow of information from the trapped nanoparticle. Its proposed setup uses a standing-wave laser to trap a nanoparticle in space with a hemispherical mirror placed around it. When the mirror has a specific radius, the scattered light from the particle and its reflection interfere so that the outgoing field no longer encodes any information about the particle’s position.

At this point, the particle is effectively invisible to the observer, with an interesting consequence: because the scattered light carries no usable information about the particle’s location, quantum backaction disappears. “I was initially convinced that we wanted to suppress the scatter,” team leader James Bateman tells Physics World. “After rigorous calculation, we arrived at the correct and surprising answer: we need to enhance the scatter.”

In fact, when scattering radiation is at its highest, the team calculated that the noise should disappear entirely. “Even though the particle shines brighter than it would in free space, we cannot tell in which direction it moves,” says Rafał Gajewski, a postdoctoral researcher at Swansea and Bateman’s co-author on a paper in Physical Review Research describing the technique.

Gajewski and Bateman’s result flips a core principle of quantum mechanics on its head. While it’s well known that measuring a quantum system disturbs it, the reverse is also true: if no information can be extracted, then no disturbance occurs, even when photons continuously bombard the particle. If physicists do need to gain information about the trapped nanoparticle, they can use a different, lower-energy laser to make their measurements, allowing experiments to be conducted at the Heisenberg limit with minimal noise.

Putting it into practice

For the method to work experimentally, the team say the mirror needs a high-quality surface and a radius that is stable with temperature changes. “Both requirements are challenging, but this level of control has been demonstrated and is achievable,” Gajewski says.

Positioning the particle precisely at the center of the hemisphere will be a further challenge, he adds, while the “disappearing” effect depends on the mirror’s reflectivity at the laser wavelength. The team is currently investigating potential solutions to both issues.

Physicists track the mass and temperature of a levitated nanoparticle

If demonstrated experimentally, the team says the technique could pave the way for quieter, more precise experiments and unlock a new generation of ultra-sensitive quantum sensors. Millen, who was not involved in the work, agrees. “I think the method used in this paper could possibly preserve quantum states in these particles, which would be very interesting,” he says.

Because nanoparticles are far more massive than atoms, Millen adds, they interact more strongly with gravity, making them ideal candidates for testing whether gravity follows the strange rules of quantum theory. “Quantum gravity – that’s like the holy grail in physics!” he says.