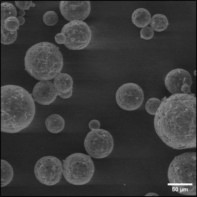

Three pioneers of lithium-ion batteries shared the 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry but after four decades of research, the implementation of the batteries has not been without obstacles. Lithium metal, an ideal anode material for its high energy density, was used in the earliest lithium battery prototypes. However, this design has been shelved due to insurmountable safety issues. Needle-like structures called dendrites form around the anode, leading to short circuiting and electrolyte depletion.

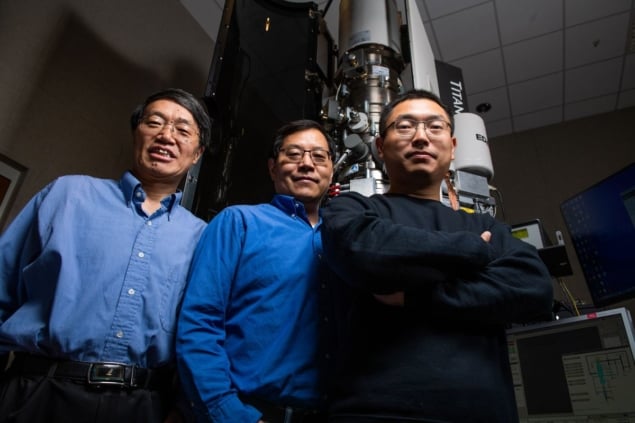

Now, researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, led by Chongmin Wang, have made significant strides in understanding lithium dendrite formation. Using in situ growth studies, they gained valuable insights for the development of safe lithium batteries.

Ion conductivity

During battery operation, the anode reacts with the surrounding electrolyte to form a porous solid electrolyte interphase layer that encases the anode. The properties of the interphase layer have a strong influence on lithium dendrite formation and morphology. Wang and colleagues used correlative transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy to monitor dendrite growth under different environmental conditions and external stressors. They discovered that dendrite formation is inhibited by ion conductivity. Lithium ions are less prone to deposit as dendrites if the interphase layer conducts ions rapidly.

Our work directly proves the correlation between dendrite morphology and its growth environment

Chongmin Wang

“Slow movement of ions in the interphase layer leads to localized deposition and then needle-shaped growth,” said Wang. “Our work directly proves the correlation between dendrite morphology and its growth environment.”

Poisoned electrolyte

These real-time observations were made in a gaseous environment, but real-world batteries and cells employ liquid electrolytes. The researchers verified their ion conductivity hypothesis in such liquid cells. When they “poisoned” the organic liquid electrolyte with ethylene carbonate, the resulting solid electrolyte interphase layer possessed lower ionic conductivity, and dendrite formation was observed once again.

Wang and colleagues propose two strategies to increase the safety levels of lithium-metal batteries. The first is to tailor the electrolyte such that only decomposition products with high ion mobility are formed in the solid electrolyte interphase. The second is to use a stiff barrier to suppress the elongation of dendrites.

The team plans to further optimize the chemical properties of the electrolyte to solve the dendrite problem once and for all. Nevertheless, they admit that the realization of rechargeable lithium-metal batteries is much more complex than eliminating the dendrite problem.

Liquefied gas electrolyte improves lithium-ion anodes

“The lithium battery is a system and all its components are interdependent,” says team member Yang He. “Changing the electrolyte to prevent dendrite growth can inadvertently alter other aspects of the battery such as the cathode-electrolyte interactions. But our work provides a guideline for screening different electrolyte recipes.”

Preventing dendrite growth would be a significant step towards harnessing the full energy density and capacity of pure lithium, to realize green, efficient, and most importantly, safer batteries.

The research is described in Nature Nanotechnology.