Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science (published as The House of Wisdom by Penguin in the US)

Jim Al-Khalili

2010 Allen Lane/Penguin £25.00/$29.95hb 336pp

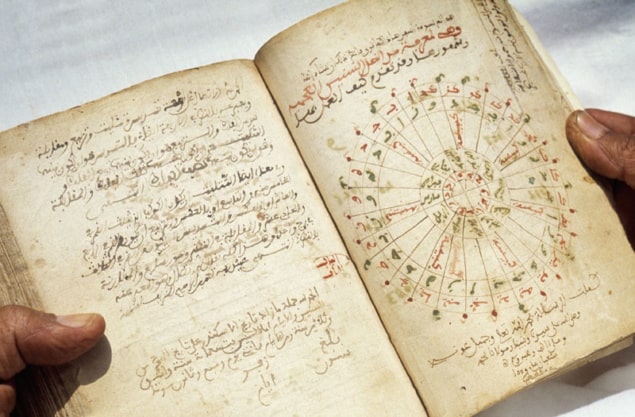

For roughly 700 years, many of the greatest scientists lived in the Islamic world. The Western narrative, however, has often neglected the contributions of major figures such as the chemist al-Jabir, the mathematician al-Khwarizmi and the medic al-Razi, preferring instead to jump directly from Aristotle, Euclid, Archimedes and Ptolemy to Copernicus and Galileo in reporting scientific development over the ages. Yet the fact is that between the eighth and 15th centuries AD, the scientists of the Islamic world developed original theories in mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine and engineering – frequently with the help of works translated into Arabic from Greek, Sanskrit, Pahlavi and Syriac sources.

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science is brimming with examples of scientific breakthroughs from this period, assembled with enthusiasm and written in a style that makes it compelling reading. The author, Jim Al-Khalili, was born in Baghdad and his book blends well his passion for his illustrious birthplace with his family history and a desire to engage a larger audience with not just the facts of science, but its history too. His knowledge of Arabic and physics provides the book with an authority that he is careful not to exceed by making unsubstantiated claims for “Arabic science”. Indeed, he initially defines “Arabic science” rather narrowly, as science “carried out by those who were politically under the rule of the Abbasids, whose official language was Arabic, or who felt obliged to write their scientific texts in Arabic”. However, he also discusses scientific activities in other dynasties and at different periods, such as the Andalusian Umayyad caliphate in Spain (929–1031) and the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt (909–1050).

One way round the difficulty of encompassing such a wide canvas would be to refer to “Islamic science” instead, but Al-Khalili provides plausible reasons for not doing so. Among them is the fact that the three scientists whose careers feature most prominently in the book – the polymaths al-Biruni and Ibn al-Haytham, and the physician-philosopher Ibn Sina – all viewed their scriptures as religious guides and not as scientific manuals. Indeed, al-Biruni, who measured the circumference of the Earth to within an accuracy of 1%, once warned that “the extremist would stamp the sciences as atheistic and would proclaim that they led people astray, in order to make ignoramuses of them, and to hate the sciences. For this will help him conceal his own ignorance”.

However, Al-Khalili’s wise choice of “Arabic” rather than “Islamic” science as his theme makes it all the more frustrating when he proceeds to label ancient Indian science as “Hindu science”. It is, in fact, a weakness of this book that its author seems preoccupied with the transmission of knowledge through Greek texts, to the neglect of contributions from the East, notably India and China. This is particularly so in the chapters on numbers and algebra. It is not sufficient just to state that the mathematical activities of these traditions have been covered well elsewhere. They are integral to any discussion of transmissions to and from the medieval Islamic world – as I have shown in my own book on the non-European roots of mathematics, The Crest of the Peacock (2010, Princeton University Press). It might have helped the author to recognize that “Arabic science” went through three stages, not necessarily chronologically: first, a period of growing awareness of other scientific traditions and the emergence of the translation project; second, a period of assimilation of scientific knowledge of different cultures (including Mesopotamian, Iranian, Indian and, of course, Greek); and last, a period of creativity and original scientific endeavours, culminating in the transmission of knowledge to Europe and elsewhere.

Aside from this flaw, the book provides a very readable account of many developments, including what the author describes as “the world’s first state-funded large-scale science project”. During the caliphates of Harun al-Rashid (786–809) and his son al-Ma’mun (809–833) an ambitious programme of construction was carried out in Baghdad that included an observatory, a library, and an institution for research named Bayt al-Hikma (“House of Wisdom”). This project brought groups of scholars together to address issues such as determining the Earth’s curvature and the coordinates of the world’s major cities and landmarks. The seminal influence of mathematical models developed by Islamic scientists on Copernicus is likewise well summed up by the author, who suggests that Copernicus should be seen as the last of the Maragha school of astronomers rather than the first modern one – a reference to an astronomical tradition that began in the 13th century at the Maragha Observatory in modern-day Iran, where scholars attempted to produce alternatives to the Ptolemaic model.

A notable point made in the book is that despite the impressive list of Arabic scientists and their achievements (a useful glossary of which is found at the back of the book), what is more important is the scientific method that they championed. They were the first group of scientists who relied on experiment and observation as well as theory, and if the data they gathered did not support the theories of Aristotle, Galen or Ptolemy, they went with the empirical results. The spirit of Mutazilism, or critical thinking and rationalism, prevailed in this culture at a time that predated the European enlightenment by about a thousand years.

A question then arises: why did Arabic science falter instead of creating a full-blown scientific revolution? Al-Khalili’s answer is interesting. He is dismissive of the usual arguments, which blame the victory of religious orthodoxy, the wars between different caliphates, or the destruction of Baghdad by the Mongolian army in 1258. Instead, the author suggests that the reason should be sought in the Islamic world’s “intense aversion” towards printing, which lasted well into the 17th century both because of the aesthetic value attached to calligraphy and because of the technical problems of typesetting Arabic script. This would have constrained the spread of ideas, preventing them from travelling as fast as they did in Europe a few centuries later. As for other technologies that might have enabled a scientific revolution, it is worth pointing out that although Al-Khalili discusses paper production (a technology of Chinese origin) and its role in the diffusion of ideas in the Islamic world, his book is short of any discussion of other technological advances made in the Islamic world.

The first book printed in Arabic (the Koran) was so riddled with errors that the Ottomans refused to buy copies from its Venetian printers. There are errors in Pathfinders as well, although they are not as serious. For example, in the chapter on numbers, there is no such thing as the “Bakhshali Theorem” referred to in endnote 2, and the earliest example of Indians working out square roots is not the “Bakhshali Manuscript” (now dated to the 7th century AD) but the Sulbasutras (dated 800–500 BC), which is also the earliest source of the Pythagorean result (i.e. a2 = b2 + c2 for a right-angled triangle). Also, the author of the Chinese text The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven is not Zhou Bi Suan Jing (this is in fact the text’s Chinese title), but an unknown scholar.

For the most part, such errors are not enough to confuse the reader. However, the errors in the illustrations in the book are irritating, if not misleading. Among other mistakes, the reader is led to expect on Plate 15 a crater on the Moon named after the Córdoban polymath ibn Firnas, only to find instead a drawing of the muscles of an eye from an ophthalmological treatise by ibn Ishaq. Also, the two maps provided at the beginning of the book do not show the locations of some places, such as Khurasan, despite the fact that they are frequently mentioned in the text; in one map, the name of the river Ebro is spelt incorrectly. Careless editing has done a great disservice to a book that otherwise has much to recommend it, as it excavates and lightens up a hidden history of Islamic science and creativity of which we are also the inheritors.