The near and far sides of the Moon are very different in their chemical composition, their magmatic activity and the thickness of their crust. The reasons for this difference are not fully understood, but a new study of rocks brought back to Earth by China’s Chang’e-6 mission has provided the beginnings of an answer. According to researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Beijing, who measured iron and potassium isotopes in four samples from the Moon’s gigantic South Pole-Aitken Basin (SPA), the discrepancy likely stems from the giant meteorite impact that created the basin.

China has been at the forefront of lunar exploration in recent years, beginning in 2007 with the launch of the lunar orbiter Chang’e-1. Since then, it has carried out several uncrewed missions to the lunar surface. In 2019, one of these, Chang’e-4, became the first craft to touch down on the far side of the Moon, landing in the SPA’s Von Kármán crater. This 2500-km-wide feature extends from the near to the far side of the Moon and is one of the oldest known impact craters in our solar system, with an estimated age of between 4.2 and 4.3 billion years old.

Next in the series was Chang’e-5, which launched in November 2020 and subsequently returned 1.7 kg of samples from the near side of the Moon – the first lunar samples brought back to Earth in nearly 50 years. Hot on the heels of this feat came the return of samples from the far side of the Moon aboard Chang’e-6 after it launched on 3 May 2024.

A hypothesis that aligns with previous results

When scientists at the CAS Institute of Geology and Geophysics and colleagues analysed these samples, they found that the ratio of potassium-41 to potassium-39 is greater in the samples from the SPA basin than in samples from the near side collected by Chang’e-5 and NASA’s Apollo missions. According to study leader Heng-Ci Tian, this potassium isotope ratio is a relic of the giant impact that formed this basin.

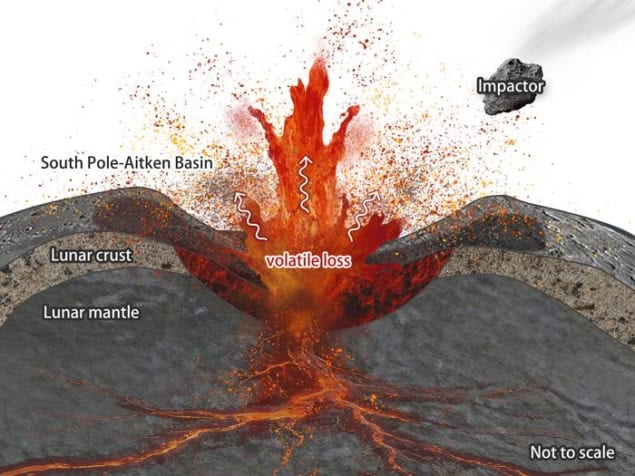

Tian explains that the impact created such intense temperatures and pressures that many of the volatile elements in the Moon’s crust and mantle – including potassium – evaporated and escaped into space. “Since the lighter potassium-39 isotope would more readily evaporate than the heavier potassium-41 isotope, the impact produced this greater ratio of potassium-41 to potassium-39,” says Tian. He adds that this explanation is also supported by earlier results, such as Chang’e 6’s discovery that the mantle on the far side contains less water than the near side.

Before drawing this conclusion, the researchers, who report their work in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, needed to rule out several other possible explanations. The options they considered included whether irradiation of the lunar surface by cosmic rays could have produced an unusual isotopic ratio, and whether magma melting, cooling and eruptive processes could have changed the composition of the basaltic rocks. They also examined the possibility that contamination from meteorites could be responsible. Ultimately, though, they concluded that these processes would have had only negligible effects.

The effects of the impact

Tian says the team’s work represents the first evidence that an impact event of this size can volatilize materials deep within the Moon. But that’s not all. The findings also offer the first direct evidence that large impacts play an important role in transforming the Moon’s crust and mantle. Fewer volatiles, for example, would limit volcanic activity by suppressing magma formation – something that would explain why the lunar far side contains so few of the vast volcanic plains, or maria, that appear dark to us when we look at the Moon’s near side from Earth.

US-led missions launched to investigate the Moon’s water

“The loss of moderately volatile elements – and likely also highly volatile elements – would have suppressed magma generation and volcanic eruptions on the far side,” Tian says. “We therefore propose that the SPA impact contributed, at least partially, to the observed hemispheric asymmetry in volcanic distribution.”

Technical challenges

Having hypothesized that moderately volatile elements could be an effective means of tracing lunar impact effects, Tian and colleagues were eager to use the Chang’e-6 samples to investigate how such a large impact affects the shallow and deep lunar interior. But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. “A major technical challenge was that the Chang’e‑6 samples consist mainly of fine-grained materials, making it difficult to select large individual grains,” he recalls. “To overcome this, we developed an ultra‑low‑consumption potassium isotope analytical protocol, which ultimately enabled high‑precision potassium isotope measurements at the milligram level.”

The current results are preliminary, and the researchers plan to analyse additional moderately volatile element isotopes to verify their conclusions. “We will also combine these findings with numerical modelling to evaluate the global-scale effects of the SPA impact,” Tian tells Physics World.