A couple of weeks ago the small satellite company Capella was alerted that another craft was on a high-speed collision course with their pathfinder, Denali. Manoeuvre commands were urgently sent to the satellite and the crisis was averted, although the two objects still passed each other very closely.

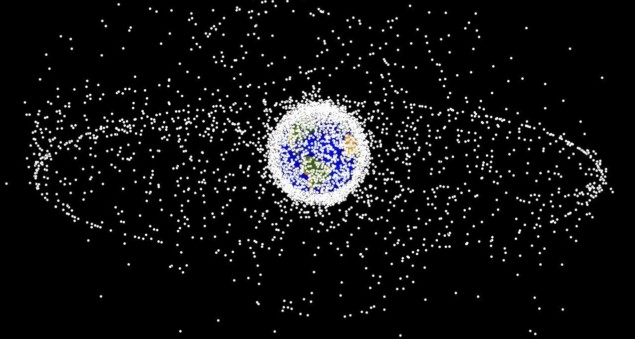

Space may be great and vast but it’s getting crowded closer to Earth. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), more than 29,000 large pieces of debris are orbiting our planet – and many more smaller bits besides. And as smaller satellites, such as the one that flew past Denali, often don’t have propulsion systems to help them avoid impact, the risk of these numbers growing is increasing.

You can find out more about orbital debris on the ESA website.

Many have gazed upon Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night in wonder. But if you’re a scientist, those famous spirals – all of varying sizes – in the painted sky might remind you instead of turbulent flow. After all, Andrei Kolmogorov’s 1941 description of subsonic turbulence does rely on vortices of different length scales.

Researchers in Australia have now published a paper weighing in on whether van Gogh’s famous artwork does indeed depict realistic turbulence.

After calculating a 2D power spectrum on a square region of painted sky, they concluded that the sky of The Starry Night is actually far more reminiscent of the supersonic turbulent flow inside molecular gas clouds. Such conditions are known to be the birthplace of stars in the universe, a coincidence that’s oddly fitting.

Now, as it’s the weekend, you might be looking forward to a cheeky glass of limoncello, the liqueur originating from southern Italy. But did you know that while water-repellent industrial chemicals usually require surfactants to mix with water, in limoncello the alcohol effortlessly keeps the citrus oil and water together.

Scientists from the Institut Laue Langevin have now examined the microscopic composition of the liqueur. They uncovered that limoncello is composed of tiny oil droplets in a water-alcohol mix. And if we can work out how the mixture forms, it could lead to many applications for essential oils in specialty chemicals as well as environmentally friendly plastics and insect repellents.

You can find out more about the research in ACS Omega.